Throughout history, the world’s mountain ranges have provided refuge for outlaws. Mountain passes, hidden caves, and steep cliffs allowed these figures to ambush travelers, evade authorities, and launch raids before vanishing into the terrain. Many began as ordinary people driven by poverty, injustice, or war into a life of crime.

Unlike the largely fictional Robin Hood, the outlaws whose stories we’ll tell today were real men who lived and died by the gun and the blade. Some of them became folk heroes and carved legends that are still remembered today in popular culture. This week, we revisit the stories of some of those legendary bad guys who chose mountains to hide from the authorities. Today: European outlaws from Scotland to Italy.

Scottish Highlands: Rob Roy MacGregor

Active in the mountains and glens of the central Highlands, Scotland’s Rob Roy MacGregor (1671–1734) is perhaps the most famous mountain outlaw in British history.

Originally a respected cattleman, he was branded an outlaw after a business deal with the Duke of Montrose went sour.

According to legend, he waged a private guerrilla war against the Duke, raiding his estates and redistributing some of the stolen rent money to poor tenants. However, it seems that historically, he was more a cattle rustler, extortionist, and vendetta-driven outlaw than a social justice figure. In one famous account, the Duke’s men captured him, but he escaped while they were crossing the River Forth.

A lifelong Jacobite, Rob Roy fought in the 1689 Battle of Killiecrankie as a young man and later raised MacGregor fighters for the 1715 uprising. Captured several times over the years and renowned for his daring escapes, his feud with Montrose continued until 1722, when he surrendered. Imprisoned and facing exile to the colonies, he was pardoned in 1727 — perhaps thanks to his growing fame fueled by early romantic biographies.

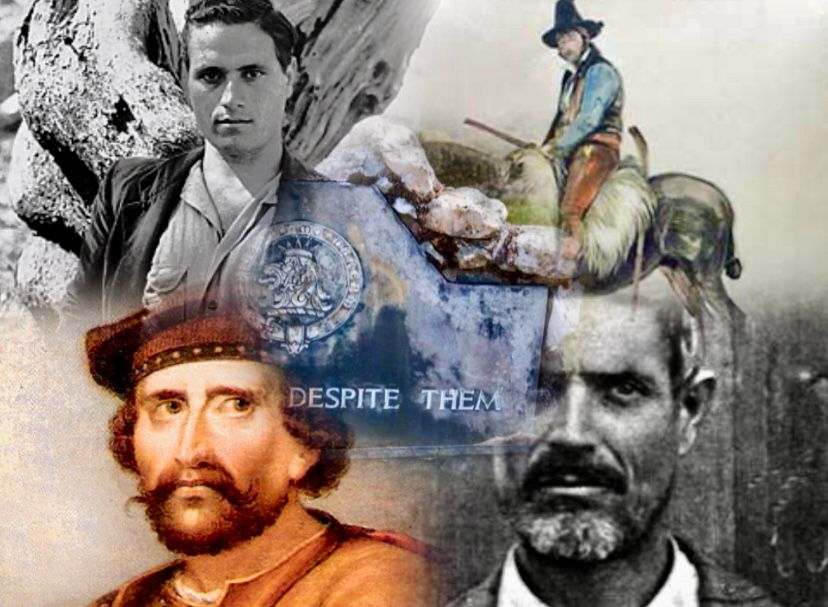

He returned home and spent his final years quietly in Balquhidder, dying peacefully in his bed in 1734. His grave in Balquhidder Kirkyard features a 1981 addition bearing the defiant inscription: “MacGregor Despite Them.”

Rob Roy MacGregor’s grave. Photo: Seelochlomond.co.uk

Spain’s Sierra Morena: the Bandoleros

El Tempranillo. Photo: Wikipedia. Artist: John Frederick Lewis

In the 18th and 19th centuries, bandoleros ruled the mountain passes of Andalusia, especially the Sierra Morena and the Serrania de Ronda.

Jose Maria Hinojosa Cobacho, nicknamed El Tempranillo (“The Early One”), turned to banditry as a teenager. He carried out his first serious crime when he was between 13 and 15 years old. He proclaimed himself king of the Sierra Morena, halting stagecoaches with a blend of ruthlessness and chivalry, such as politely returning jewels to ladies who treated him with respect.

The romantic age of the Spanish bandolero ended for good in the spring of 1934 with the death of Juan Jose Mingolla Gallardo, known as Pasos Largos (“Long Steps”), considered the last traditional bandit. The Guardia Civil killed him in a shootout in a cave in the Sierra Blanquilla, near Ronda, in southern Spain.

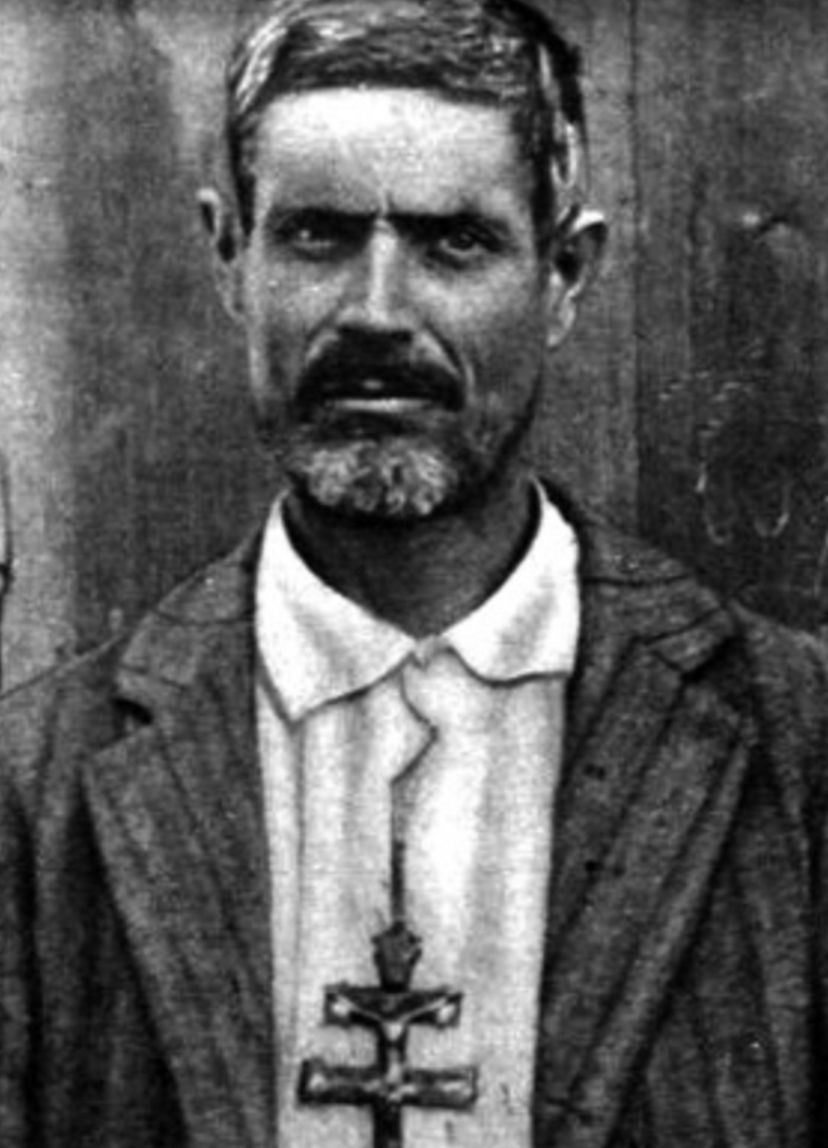

Juan Jose Mingolla Gallardo. Photo: laescaleradeiakob.blogspot

Sicily’s Hills: Salvatore Giuliano

Italian Salvatore Giuliano was born into a peasant family in 1922 in Montelepre, a small town near Palermo. He left school early to work on the farm and later traded olive oil. During World War II, black market dealings were common. In September 1943, police stopped him while he was smuggling grain. A fight broke out, and he shot an officer and fled into the nearby hills.

Wounded, he hid in caves and got help from locals. Soon, he formed a small band of about 20 men, mostly farmers and deserters. They robbed rich landowners, kidnapped for ransom, and ambushed travelers. Giuliano often gave part of the money to villagers. He paid well for food and shelter. Peasants protected him under the old code of silence. To them, he was a defender against greedy elites and a distant government.

His life soon mixed crime with politics. In 1945, Giuliano joined the Sicilian separatist movement. They wanted independence from Italy. He became a “colonel” in their armed wing and attacked police posts. He hated communists and linked up with right-wing figures, the Mafia, and even American agents.

On May 1, 1947, his band fired from the hills on a peasant rally at Portella della Ginestra, a mountain pass. Eleven people died, including children. The attack aimed to scare leftists but became a massacre. Many believe bigger forces used him for their own ends.

Salvatore Giuliano. Photo: Michael Stern

By 1950, the hunt closed in. His allies turned against him, and his trusted deputy, Gaspare Pisciotta, betrayed him to the police. (Betrayal has been a recurrent theme throughout this outlaw series.) On July 5, 1950, Giuliano was shot dead while asleep. He was only 27.

Officials staged the scene as a gun battle. Pisciotta later confessed and was poisoned in prison. Rumors said Giuliano escaped overseas, but DNA tests in 2010–2012 confirmed the body was almost certainly his.

Giuliano remains a complicated legend. Songs, books, and films keep his story alive. Some see him as Sicily’s Robin Hood. Others view him as a tool of the powerful. Either way, he was one of the last of Europe’s true mountain outlaws.