Annie Smith Peck was an American teacher who became a pioneering mountain climber during the suffragette movement. She famously hung a “Votes for Women” flag on the summit of Peru’s Coropuna. Although she remains the only woman ever to make a first ascent of a major peak, her choice of climbing attire often overshadowed her climbing accomplishments.

Born in 1850, Peck was the only sister to four brothers. She grew up with a competitive streak. Like pioneer woman traveler Ida Pfeiffer, she felt that she could do anything her brothers did. However, education was one area in which, despite her persistence, she was forced to stop early.

Eventually, when she was in her late twenties, and after years of unwavering pleas, her father supported her desire to enroll at the University of Michigan. Enrollments for women had only opened three years earlier.

Her late start didn’t hold her back. Peck graduated as a teacher of mathematics and languages. She then furthered her studies in classical languages, which is how her world eventually collided with climbing.

The Matterhorn

While traveling from Germany to Greece to attend the American School of Classical Studies in Athens (the first woman to do so), Peck saw the Matterhorn for the first time. The chance encounter changed her life. From then on, she would use her career to support her love of travel and mountaineering.

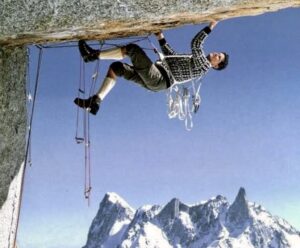

Annie Peck shocked the world when she wore pants while mountain climbing.

It wasn’t normal for women to climb mountains. In the 1880s, one deterrent for women was how difficult it was to find practical clothing for sport and outdoor endeavors. It was another 40 years before the first mountaineering and climbing instructional book included a chapter titled For the lady mountaineer. When Henriette d’Angeville summited Mont Blanc in 1832, she wore a petticoat over men’s pants and a boa. The outfit weighed more than six kilograms.

Peck and other women climbers faced the same dangers as their male counterparts, with the additional challenge of climbing in socially appropriate clothing. When Peck was starting out as a climber, she was expected to dress as though she was going to the market.

Peck didn’t let these restrictions stop her. Her first ascents of moderate peaks in Europe and the United States aimed at building strength and skill level. She climbed in pants and quickly grew an unwanted reputation as the “trouser-wearing climber”. Undeterred, she began looking for a bigger challenge. In 1895, she summited the Matterhorn.

The Matterhorn earned Peck celebrity status. However, her steely determination, strength, and remarkable courage continued to play second to the controversy over her attire. She climbed in a hip-length tunic, tall climbing boots, baggy-kneed knickerbocker pants, and a felt hat secured with a veil. Her decision to wear pants left many people questioning why she hadn’t been arrested, a legitimate possibility in 1895!

The first ascent of Huascaran

After the Matterhorn, Peck was unstoppable. Over the next few years, she climbed Orizaba in Mexico (at the time, the highest climb by any woman in the Americas), Cristallo in the Italian Dolomites, the Jungfrau in the Swiss Alps, and the Funffingerspitze in Austria.

In 1902, she and three other women were among the founding members of the American Alpine Club (AAC). By now, Peck was over 50 but she showed no signs of slowing down. She was ready for another record-setting climb.

In 1903, she began the first of two attempts on Illampu in Bolivia. Then in 1908, at 58, Peck climbed the north peak of Huascaran in Peru with two Swiss guides. The 6,768m achievement had taken her four years and five failed attempts. Because Huascaran had never been accurately measured, Peck believed she had broken two records: the highest mountain in the western hemisphere, and the world altitude record for both men and women.

Conflict over the record

Her summit was a world first and the north peak was later named Cumbre Ana Peck, in her honor. But the climb generated controversy.

Fellow AAC founding member, Fanny Workman, had held the highest altitude record. Workman didn’t much like the idea of having the title taken from her and paid engineers to recalculate Huascaran’s altitude. The engineers triangulated the peak and established that Peck had misjudged her calculations by 600m. Workman retained her record.

Public conflict ensued. Peck was accused of purposely exaggerating the mountain’s size. She described the controversy as harder than the climb itself, during which one of her Swiss guides lost a hand and half a foot to frostbite. The climb had been “a horrible nightmare,” but the public arguments were worse. To help her cope, she even contacted polar explorer Robert Peary, who was no stranger to controversy.

The suffragette movement

Peck, an ardent suffragist, had perhaps inadvertently been shining a spotlight on women’s rights. Her male climbing attire and leadership role at the ACC was helping break entrenched gender norms. Now, she took a more direct stand. In 1911, at the age of 61, Peck headed to Peru and climbed five of Coropuna’s peaks. On one summit, she placed a “Votes for Women” banner.

Her banner was one of many links between the suffragettes and mountaineers. The first was Cora Smith Eaton’s “Votes for Women” banner, planted on Mount Rainier’s summit. Eaton also wrote “Votes for Women” after her name in the register at the top of Glacier Peak.

A flyer for a series of lectures by Annie Peck.

Peck continued to push boundaries well into her twilight years. In 1929, she set off on a seven-month trip around South America. Using commercial aircraft, her trip was the longest by air of any North American traveler at the time. At the age of 82, she climbed her final mountain, Mount Madison.

When Peck died at age 84, she was in the midst of a world tour. She became ill while climbing the Acropolis in Athens. She returned home but died of pneumonia.

Although her climbing accomplishments aren’t widely known, Peck’s legacy remains. In her lifetime, she published four books about her travels: The Search for the Apex of America (1911), The South American Tour (1913), Industrial and Commercial South America (1922), Flying Over South America: Twenty Thousand Miles by Air (1932).

She received several awards including the Decoration al Merito by the Chilean government and a gold medal awarded by the government of Peru for her contribution to South American trade and industry.

“Climbing is unadulterated hard labor,” Peck once wrote. “the only real pleasure is the satisfaction of going where no man has been before, and where few can follow.”