Nepal’s Department of Tourism is determined to enlarge its list of 8,000m peaks by adding six secondary summits on Kangchenjunga and Lhotse. However, this campaign to promote mountaineering tourism will not change international criteria or mountaineering history around the 14 highest peaks on Earth.

The Department of Tourism added six “new” 8,000’ers to its official website, Nepal Peak Profile. Now, it will try to get the new list approved by various stakeholders, including tourism entrepreneurs, the Nepal Mountaineering Association, and the army and police forces. It will then lobby for the new inclusions at international forums, The Kathmandu Post reports.

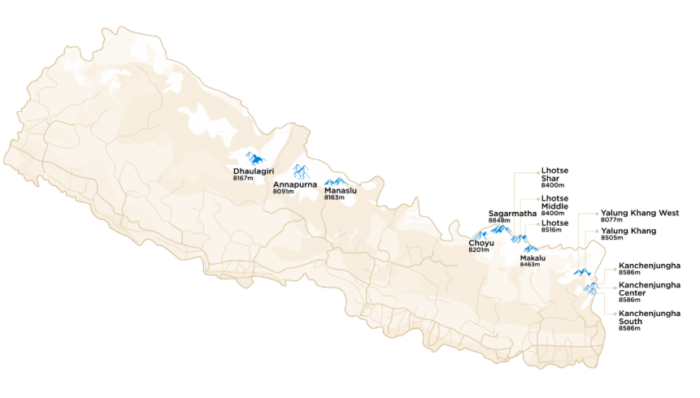

The map of the summits ranked by Nepal’s DoT as the Top 14 highest mountains of Nepal. Map: Nepal Peak Profile

This isn’t exactly news. Two years ago, Nepal Tourism quoted a team of local experts who suggested the list of 8,000’ers should include the four lesser points of Kangchenjunga — Yalung Khang (8,505m), Yalung Khang West (8,077m), Kangchenjunga Central (8,473m), and Kangchenjunga South (8,476m) — as well as two extra points on the summit ridge of Lhotse — Lhotse Middle (8,410m) and Lhotse Shar (8,400m).

Secondary summits

However, as we wrote in a long feature story at the time, there are only eight 8,000m peaks in Nepal. All the others are just secondary summits.

In fact, the mountain website 8,000ers.com shows that there are even more secondary summits than those mentioned by Nepal’s Department of Tourism. Everest and Annapurna also have subsidiary summits that surpass 8,000m. Pakistan’s K2 and Nanga Parbat have these features too, as does Tibet, thanks to the Central Summit of Shisha Pangma.

8000ers.com’s list of subsidiary 8,000m summits.

Since 2023, Nepalese experts have encouraged the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA) to take a stand on the matter. According to The Kathmandu Post, these experts are still waiting to hear back from the UIAA. However, the UIAA made its position clear in October 2023, although it was not what Nepal’s Department of Tourism had hoped for.

UIAA: peaks vs summits

After it received the Nepal Mountaineering Association request in 2023, the UIAA issued a report that fall. It pointed out that the crux of the debate is whether mountains are peaks or summits/tops. The 14 eight-thousanders are 14 peaks, no matter how many secondary and tertiary summits they have.

Not surprisingly, there is no clear consensus about what exactly differentiates a peak from a summit. Resisting the temptation to be dogmatic, the UIAA asked the Commission of Mountain Studies of the International Geographical Union for its opinion. It also consulted its own experts.

They considered topographical details, the historical outlook, the interests of the local communities and the Government of Nepal, the previous UIAA experience in defining alpine peaks over 4,000m, and the “spiritual” aspects of individual cases.

Traversing the points of Kangchenjunga, an old project by Simone Moro and Tamara Lunger. Photo: GoreTex website

According to their previous criteria with 4,000’ers in the European Alps, a peak needs distinctive features and a certain prominence and separation from the main summit of a massif. That is necessary but not sufficient. For example, Kangchenjunga’s secondary summits show a certain prominence and clear features, but the UIAA experts also considered the meaning of the Sikkimese name Kangchenjunga -– the “Five Treasures of the Great Snow.”

Five peaks, one mountain

“It is clear that the local population considers the five peaks to be one mountain,” the UIAA concluded.

The same applies to Lhotse Shar and Lhotse South, which are “considered part of a greater mountain mass.” The UIAA adds that the worldwide mountaineering community universally recognizes the classical classification of the 14 8,000’ers.

“Since that is the community, together with the local population, which has the most interest in these mountains, it is perhaps appropriate that this definition be used,” it argued, then concluded:

It is therefore the opinion of the UIAA that the number of mountains over 8,000 meters be recognized as the “classic” 14 peaks. Should the Nepalese government, for administrative and other reasons, choose to recognize more summits, they are, of course, entirely within their rights.

Meanwhile, unilaterally adding additional 8,000m summits to the Nepal Peak Profile website should have little impact. International climbers don’t use the site as a reference because it is often outdated and includes incorrect or confusing data about altitudes and ascents.

Unclear business impact

Nepal’s lobbyists have always openly stated that the campaign aims to promote tourism and boost the climbing expedition industry.

“If internationally recognized, Nepal could see increased tourism revenue, as climbers looking to set records or achieve new feats would seek permits for these additional peaks,” The Kathmandu Post reported.

All the secondary points mentioned are already open to climbers, so anyone can choose to attempt them. But the problem is the price of the permits. A permit for the main summit does not include those secondary summits or even the right to a package discount. Horia Colibasanu of Romania and Peter Hamor of Slovakia had to abandon their goal of traversing from Kangchenjunga Main to Yalung Khan in 2022 because they would have had to pay for the lesser summit as a separate 8,000’er.

Lhotse Middle is hardly a place for commercial expeditions. Photo: Yuri Koshelenko

It is also unclear whether expedition outfitters will want to commercialize these secondary summits. All of them include daunting technical sections. The ascents of Lhotse Shar and Lhotse Middle have led to some mountaineering epics, but neither is suitable for guided clients, even assuming that clients would be interested.

Of course, a frenzied market exists to set records, sometimes senseless, on the world’s highest peaks. However, climbing difficult and expensive secondary points is not a popular choice for record seekers and social media celebrities today. If that’s the plan, the outfitters’ marketing teams have a challenge ahead of them.