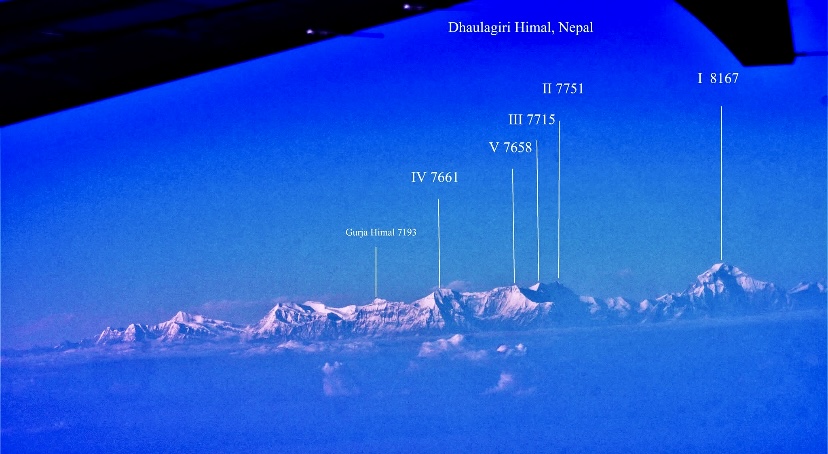

Nepal’s Dhaulagiri massif is 120km long, but its highest peaks all fit into a 50km stretch. Dominated by 8,167m Dhaulagiri I, the seventh-highest peak in the world, the massif also includes 7,751m Dhaulagiri II, and subsidiary peaks like Dhaulagiri III (7,715m), Dhaulagiri IV (7,661m), Dhaulagiri V (7,618m), and Dhaulagiri VI (7,268m).

In 1969, the Dhaulagiri massif witnessed an unprecedented death toll. Thirteen climbers from two expeditions died in what was the deadliest year in Dhaulagiri’s history. The tragedies occurred on Dhaulagiri I and Dhaulagiri IV, roughly 15km apart, involving American and Austrian teams. To understand what unfolded that year, we must first examine the mountain’s reputation through the lens of its early pioneers.

Early attempts on Dhaulagiri I

Before 1960, seven expeditions attempted the first ascent of Dhaulagiri I.

According to The Himalayan Database, there was a rumored attempt to climb Dhaulagiri I in 1949. However, there are no details of the climbers’ names or attempted route.

In the spring of 1953, a Swiss party from the Zurich Academic Alpine Club, led by Bernhard Lauterburg, tried to summit via the North Face with bottled oxygen. They gave up at 7,700m when confronted with difficult rock climbing.

In 1954, an Argentinian-Austrian-Chilean expedition led by Francisco Ibanez made a better attempt on the North Face, again with supplemental oxygen. However, on June 1, they turned back at 8,000m due to exhaustion and difficulty with the route.

During the attempt, Ibanez suffered severe frostbite on both legs at 7,500m. He died on June 30 in a hospital in Kathmandu, becoming the first registered death on Dhaulagiri.

In the spring of 1955, a German-Swiss expedition led by Martin Meier abandoned their North Face route at 7,600m in bad weather and heavy snow.

Francisco Ibanez with severe frostbite on his legs. He died later in a hospital in Kathmandu. Photo: Culturademontania.org.ar

In the spring of 1956, an Argentine-Indian expedition led by Emiliano Huerta reached 7,700m via the North Face. They turned back due to minimal supplies, poor organization, and a lack of oxygen. Nepalese porter Bal Bahadur died in an avalanche at 5,300m while preparing the route.

In the spring of 1958, Werner Staeuble led a Swiss-Polish-German party to the North Face. Deep snow and avalanche risk made them give up the attempt at 7,600m.

In the spring of 1959, Austrian climbers led by Fritz Moravec tried the Northeast Ridge, but high winds frustrated their climb at 7,800m. While preparing the route on April 29, Heinrich Roiss fell into a crevasse near Camp 2 at 5,700m and died.

Other pre-1969 attempts

In the spring of 1959, a Japanese party led by Kiichiro Kato scouted Dhaulagiri II’s north side, but did not climb.

In the autumn of 1962, a South Korean party led by Park Chul-Am attempted Dhaulagiri II by the East Ridge from the north. They reached 7,750m without supplemental oxygen.

In the spring of 1963, Austrian climbers led by Egbert Eidher tried the same route as the South Koreans. Their highest point was 7,000m, where they turned around in bad weather. Eidher’s party also attempted to climb 7,715m Dhaulagiri III during the same expedition, reaching 6,500m on the north side.

In the spring of 1965, a Japanese expedition led by Hiroshi Sugita attempted Dhaulagiri II by the East Ridge from the north without supplemental oxygen. They abandoned at 5,400m in deep snow. An avalanche killed Lhakpa Gelbu Sherpa and Mingma Tenzing Sherpa while they were scouting for somewhere to set up Base Camp.

In the autumn of 1962, a British team reached 6,400m on Dhaulagiri VI. Three years later, members of the British Royal Air Force Dhaulagiri Expedition turned back at 6,400m on the same subsidiary peak because of a windslab avalanche.

Dhaulagiri IV had not seen any attempts before 1969.

The Dhaulagiri massif from a flight. Photo: Raj Kumar Khosla/The Himalayan Club

The first ascent in the massif: Dhaulagiri I

Finally, in the spring of 1960, eight international climbers led by Swiss mountaineer Max Eiselin succeeded on Dhaulagiri I. Their Northeast Ridge climb was the first ascent of any peak in the Dhaulagiri massif.

On May 13, Kurt Diemberger from Austria, Peter Diener from Germany (West Germany at the time), Ernst Forrer and Albin Schelbert from Switzerland, and Nawang Dorje Sherpa and Nima Dorje Sherpa from Nepal, topped out without supplemental oxygen. Swiss climbers Michel Vaucher and Hugo Weber also succeeded 10 days later.

Albin Schelbert, Nawang Dorje, Nima Dorje, and Ernst Forrer on the summit of Dhaulagiri I in 1960. Photo: Kurt Diemberger

The 1969 American team on Dhaulagiri I

The American expedition in 1969 was initially planned as a reconnaissance for a potential summit push in 1970, after shifting from other peaks because of permission issues. Sponsored by the American Alpine Club and led by Boyd Nixon Everett Jr., the team would attempt the unclimbed Southeast Ridge, a sharp, exposed feature promising technical challenges.

The team consisted of 10 climbers: Boyd Everett (leader), Al Read (deputy leader), Jeff Duenwald, Paul Gerhard, Vin Hoeman, Jim Janney, Jim Morrissey, Lou Reichardt, Bill Ross, M.D., and Dave Seidman. Transportation officer Terry Bech, liaison officer Hari Das Rai, and several Sherpas and porters, including Tenzing Sherpa, Pemba Phutar Sherpa, and Mingma Norbu Sherpa, supported the 10 climbers.

The lower section of Dhaulagiri I. Photo: Tommy Joyce

The leader’s credentials

The team leader, Boyd N. Everett Jr., was a 36-year-old securities analyst from New York. A Harvard graduate, Everett balanced a career in investment banking with a passion for mountaineering. He started climbing in 1957 and rapidly amassed a portfolio of bold ascents on North American peaks. In 1962, he led the first ascent of Denali’s Southeast Spur, an eight-kilometer ridge from the Ruth Glacier. This project, initially met with skepticism in Alaska’s climbing circles, highlighted his organizational prowess. Everett summited the four highest peaks in North America: Denali, Mount Logan, Pico de Orizaba, and Mount Saint Elias, often via new routes.

His 1968 South American expedition served as preparation for the Himalaya. Everett had originally eyed K2 but shifted to Dhaulagiri I after permit complications. Everett’s leadership style emphasized meticulous planning and team cohesion, traits that earned him respect in the American Alpine Club.

Steady progress

The expedition arrived in Nepal in early spring 1969, establishing Base Camp at 4,570m on the East Dhaulagiri Glacier by mid-April. The route involved navigating treacherous glacier terrain, prone to serac falls and ice avalanches. These hazards would prove fatal.

The climbers progressed steadily at first, setting up camps along the glacier and ferrying loads to an advance base. However, challenges emerged early. Read suffered severe acute mountain sickness, developing pulmonary edema and brain swelling. He fell unconscious, and the team evacuated him down the glacier on April 22. Read recovered with some residual weakness and vision impairment in one eye.

Dhaulagiri I. Photo: Sergey Ashmarin

Route difficulty

The team, lacking prior Himalayan experience, relied on Sherpa support for route-finding. After Read’s evacuation, Hoeman and Reichardt climbed alone to 5,180m on the glacier on moderately easy terrain. The next morning, joined by Gerhard, they advanced to 5,330m, where a large crevasse blocked the path at the lower rim of a huge basin. They requested wooden logs from below to bridge it and returned to Base Camp that evening.

Progress continued over the following days. Around April 25, Pemba Phutar Sherpa and Tenzing Sherpa carried a small tent, food, and climbing gear to the crevasse edge, planning to stay and explore further. Everett, Seidman, and Ross occupied the old campsite. The next morning, Ross and Reichardt waited for Mingma Norbu to deliver the logs, then set out carrying them to the crevasse. There, the full group of eight rigged ropes, unloaded, and inspected the route as afternoon fog descended.

Disaster

Just as Ross and Hoeman finished pivoting the logs into place on the far rim of the crevasse, a massive ice avalanche, triggered by the collapse of a triangular ice cliff, roared down the mountain.

According to an account in the American Alpine Journal, the slide cut a 30m wide swath across the broad basin, filled the crevasse, and overwhelmed the group in an instant. The scene afterward was “uncannily silent and peaceful on a warm, misty afternoon.”

Seven people vanished in the chaos: five Americans (Everett, Gerhard, Hoeman, Ross, and Seidman), and two Sherpas (Pemba Phutar Sherpa and Tenzing Sherpa). The violence of the event was overwhelming, leaving a blank, white landscape where the group had stood moments before. The force of the ice was so immense that it deposited debris well below the point of impact, plunging over a high cliff.

Small snow slides on the lower sections of Dhaulagiri I near Base Camp in 2021. Poto: Luis Soriano

The sole survivor

Of the eight men, only Reichardt survived, miraculously left unhurt at the very edge of the slide. According to Reichardt’s account, he dove into a slight change in the slope for shelter. Though he was repeatedly struck on the back with glancing debris blows, he held on. When it ended, he stood up, expecting to see his seven companions. Instead, “everything that was familiar — friends, equipment, even the snow on which we had been standing — was gone. There was only dirty, hard glacial ice with dozens of fresh gouges and scattered huge ice blocks, the grit of the avalanche.”

After an hour futilely searching the football-field-sized, six-meter-deep ice mass, Reichardt made a lonely descent to Base Camp. There, he alerted the rest of the expedition. A rescue party climbed back up to the debris that evening and searched until after dark, but they found only scattered, shredded gear. It was clear that the seven men were lost forever, buried deep within the crevasse or under tons of ice.

Aftermath

Efforts continued over the next week to retrieve what equipment they could, not for its value, but from emotional reluctance to sever ties with their lost companions. The tragedy profoundly impacted the Sherpa community too, with Tenzing leaving a wife and three young children, and Pemba Phutar leaving a wife and five children. Following the disaster, their families faced burdens of religious tradition and financial survival, requiring 4,000 to 5,000 rupees for a traditional 49-day funeral service and 15,000 rupees for the education of eight children.

The 1969 Dhaulagiri I incident was the worst single-event disaster in Nepalese mountaineering at the time. The survivors determined that recovering the bodies from the ice was impossible. The expedition was abandoned soon after.

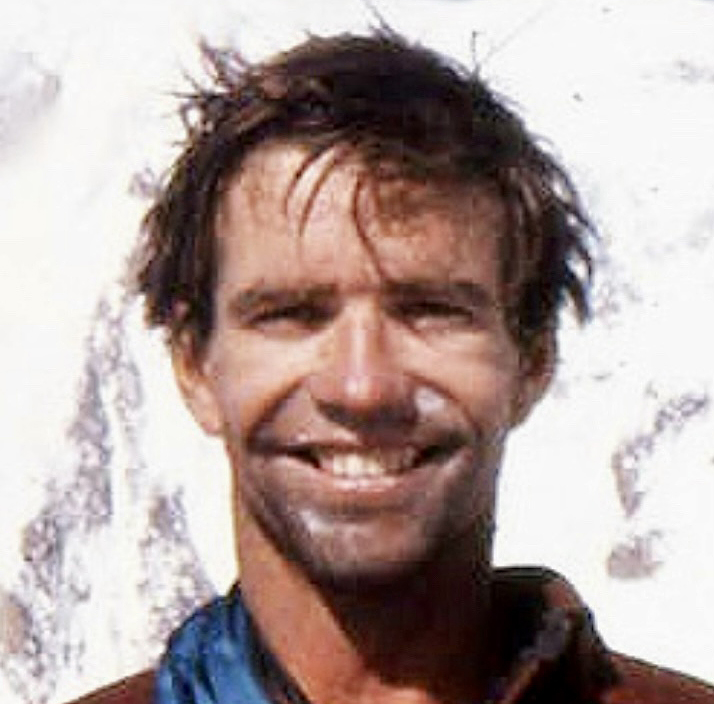

The trauma lingered, but Reichardt channeled it into determination. He returned to Dhaulagiri I in 1973 with another American team, summiting via the Northeast Ridge on May 12 alongside John Roskelley and Sherpa Nawang Samden Sherpa. That 1973 ascent, the mountain’s third overall, provided a measure of closure.

Lou Reichardt. Photo: Goat.cz

The 1969 Austrian expedition to Dhaulagiri IV

Months after the American tragedy, an Austrian team targeted the unclimbed subsidiary peak Dhaulagiri IV. Organized by the Austrian Alpine Association, the expedition included nine Austrians and six Sherpas. They shifted from an initial plan for India’s Shivling due to restrictions, opting instead for Dhaulagiri IV via Pokhara and the Myagdi Khola and Choriban Khola Valleys. They established Base Camp at 3,450m–3,800m in the Konaban Gorge on October 1, amid lingering monsoon rains.

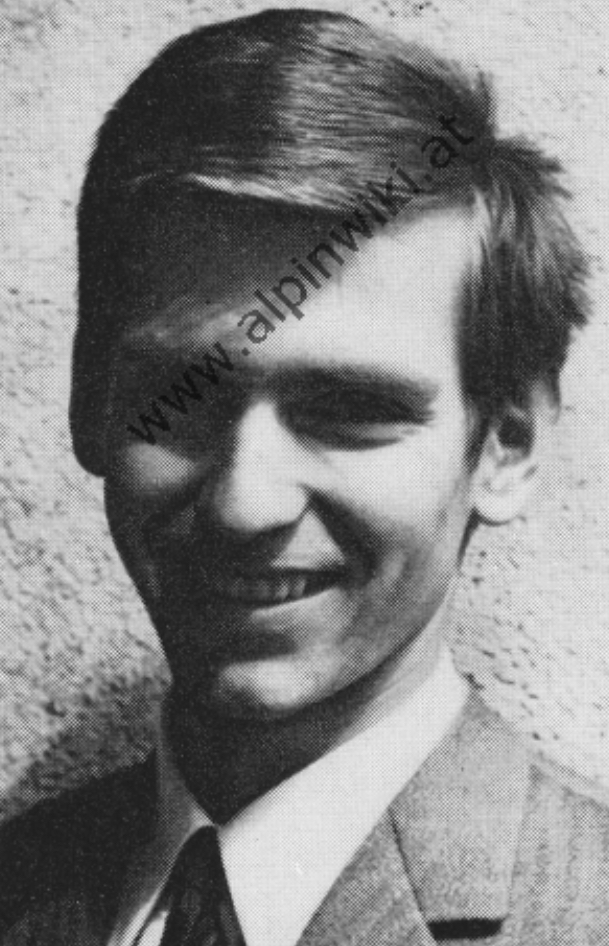

Team leader Richard Hoyer was a rising star in Austrian mountaineering. His portfolio included the north faces of the Westliche Zinne, the Matterhorn, Piz Badile, and Grand Capucin; the Bonatti Pillar on the Petit Dru; the Walker Spur on the Grandes Jorasses; and the Brenva Face and Peuterey Ridge on Mont Blanc. In the Caucasus, he traversed Ushba and climbed the Bezengi Wall. He summited Pik Lenin in the Pamirs and claimed first ascents like the Direkte Nordostwand of Admonter Reichenstein and Grazerweg on Tellersack. At 26, he embodied the era’s ambitious alpinism.

Richard Hoyer. Photo: Alpinwiki.at

Ready for the summit push

Their route ascended a southeasterly ridge, overcoming a 200m rock wall and ice barriers using fixed ropes. They set up camps progressively: Camp 1 at 5,100m, Camp 2 at 5,800m, Camp 3 at 6,200m, Camp 4 as a depot, and Camp 5 at 6,900m on a sharp saddle by November 9. Challenges included daily afternoon snowfalls obliterating tracks, Sherpa illnesses like bronchitis, and the ridge’s difficulty, compared by the climbers to Mont Blanc’s Peuterey.

On November 9, the summit party — Hoyer, Peter Lavicka, Peter Nemec, Kurt Ring, Kurt Reha, and Tenzing Nindra Sherpa — rested at Camp 5, reporting good conditions via radio at 6 pm. They planned a 3 am start on November 10 for the west ridge to the summit, with check-ins scheduled. The weather began clear but clouded by 9 am, bringing rain at base camp and likely snow higher on the mountain. There was no further contact with the summit team, despite hourly attempts.

Failed searches

Support from lower camps faltered. Deputy leader Leo Graf and Sherpas reached Camp 1 on November 12, but snow and illness forced them to retreat by November 16. Aerial searches began on November 21, with a helicopter piloted by Jai Singh circling up to 6,400m in clear weather. Singh spotted no tents, tracks, or people amid 111kph winds. Further flights, including plans for north-side inspections, could not fly in stormy weather. Ground efforts by survivors like Graf, Oskar Krammer, Dr. Klaus Kubiena, and Wolfgang Muller-Jungbluth failed to access the ridge.

The party was presumed lost between November 10 and 12, possibly from a cornice break on the exposed ridge. Radio failure was unlikely, given prior reliability. Like the American incident, no remains surfaced, amplifying the grief. Funding for additional searches hinged on signs of life that never appeared. Finally, they dismantled Base Camp and went home.

Dhaulagiri IV. Photo: Sanjib Gurung/Nepal Himal Peak Profile

Legacy of loss

The 13 deaths in 1969 remain unmatched in the massif’s history.

Dhaulagiri IV was first ascended on May 9, 1975, by Shiro Kawazu and Etsuro Yasuda of Japan. They climbed via the Junction Peak-West Ridge route from the southwest, without supplemental oxygen. Kawazu and Yasuda confirmed their successful ascent by radio, but both died on the descent in a fatal fall at 7,400m.

Dhaulagiri IV’s statistics are scary. It has only 13 summits, the most recent by another Japanese team in the autumn of 1975. Meanwhile, 14 climbers have perished on Dhaulagiri IV.

Decades after the 1969 disasters, the massif’s lethal reputation was reaffirmed in 2018, when a single event on Gurja Himal (a peak located on the western edge of the Dhaulagiri massif) surpassed even the Dhaulagiri I avalanche of 1969 in total fatalities. Among the fallen was the legendary South Korean climber Kim Chang-ho.

Memorial stone in Vienna Central Cemetery for the 1969 Austrian expeditions’ victims of Dhaulagiri IV. Photo: Viennatouristguide.at