Marc-Andre Leclerc loved mountains for the adventure, not for the fame. He achieved incredible things, winter soloing Torre Egger in Patagonia and free climbing El Capitan’s Muir Wall, among other notable climbs. He was never nominated for a Piolet d’Or, but Leclerc didn’t care about awards.

Leclerc thought chasing records or attention took away from the real experience of climbing.

“The obsession with time and speed is one of the greatest detractors from the alpine experience,” he wrote.

His 2016 solo climb of Mount Robson’s Emperor Face, a tough 1,500m wall in the Canadian Rockies, demonstrates this climbing ethos.

Mount Robson and its first ascent

Mount Robson (3,954m) in British Columbia’s Mount Robson Provincial Park is the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies. The Secwepemc people call it Yexyexescen, meaning “striped rock,” and see it as sacred. Europeans named it after fur trader Colin Robertson. Its height and bad weather, with lots of snow and wind from the Pacific, make it a hard climb.

Mount Robson panorama. Photo: Wikimedia

In 1909, Arthur Oliver Wheeler explored Mount Robson but couldn’t summit. In 1913, George Kinney and Curly Phillips skied to the base. That same year, at the end of July, Albert MacCarthy, William Foster, and guide Conrad Kain reached the top via the northeast Kain Face. They cut over 1,600 ice steps, making it North America’s hardest ice climb at the time. Kain said: “God made the mountains, but good God! Who made Robson?”

From 1939 to 1953, no one summited the peak, but after World War II, new routes opened. In 1951, climbers tackled the Southeast Face. In 1962, Steve Roper and Allen Steck climbed the Wishbone Arete, which was listed in the book Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. However, the steep northwestern wall, the brutal Emperor Face of ice, rock, and snowy gullies, was the real challenge.

Mike Perla and Jim Spencer first completed the impressive Emperor Ridge, which is the northwest ridge, in 1961.

Mount Robson’s Emperor Face (the right half of the picture), with Berg Lake in front. Photo: Jeff Pang via Canada Navanture/Facebook

Ascents of the Emperor Face

In July 1978, James Logan and Mugs Stump made the first ascent of the Emperor Face, via a difficult VI 5.9 A2 route to the summit ridge. Logan had tried and failed to climb the face in 1976 and 1977, each unsuccessful attempt fueling his determination to succeed on a face that he found more impressive than the Eiger. After an unsuccessful climb on Mount Logan’s Hummingbird Ridge and waiting out two weeks of rain below the Emperor Face, a clear day finally gave them their chance.

They set up a camp high on the lower snow slopes, having already climbed 914m of easier snow and rock, carrying 25 pitons and eight days’ of food. The climb pushed their skills and courage, with steep 60° ice, thin ice over vertical rock steps, and few safe spots to place gear. Instead, they relied on shaky pitons or tied-off screws.

A summer view of Mount Robson, with the snow-streaked Emperor Face at the far right. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

On the first day, Stump and Logan reached a snow rib in the center of the face, a spot previously reached by Pat Callis and Jim Kanzler, the highest point on earlier attempts. The next day was grueling, with every other section extremely hard: thin ice, loose rock, and an overhanging wall. Logan’s key section involved carefully placing pitons and climbing loose, snow-covered rock. He nearly fell when a crampon slipped.

“At such times, I can climb much better than usual, and fortunately can often muster this frame of mind on serious climbs where it is most needed,” Logan wrote, describing the intense focus, shaped by his earlier failed tries, that kept them going.

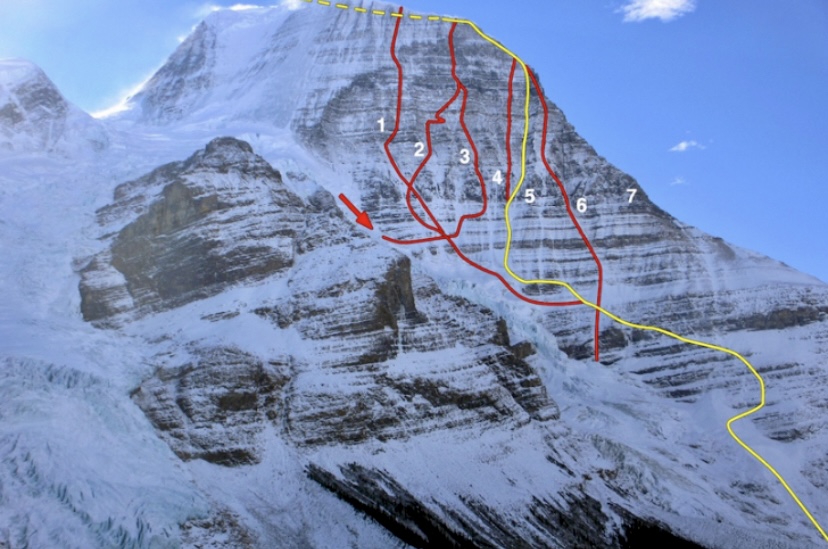

Routes on the Emperor Face of Mount Robson. (1) Cheesmond-Dick 1981; (2) Logan-Stump 1978, the first ascent of the Face; (3) Haley-House 2007; (4) Kruk-Walsh 2010; (5) Berman-Hawthorn 2020; (6) Infinite Patience, Blanchard-Dumerac-Pellet 2002; (7) Emperor Ridge, Perla-Spencer 1961. Photo and explanation: Ethan Berman for the American Alpine Journal

A night of avalanches

Despite a scary night camped on 70° ice with snow avalanches pouring over them, Logan and Stump kept climbing. Stump led up steep ice to the final wall, and Logan’s careful piton work and risk-free climbing got them to the north face’s snowy slopes. Tired but successful, they pushed through a snow cornice to reach the ridge, then chose to descend the south face instead of going to the summit, which Logan had already reached on a previous trip. For Logan, beating the Emperor Face, after years of failed attempts, was the real victory.

Dave Cheesmond and Tony Dick made the first complete ascent of the Emperor Face to the summit in August 1981.

A closer view of the Emperor Face. Photo: Summitpost

After the 1981 ascent, and before Leclerc’s solo climb of the Emperor Face in 2016, there were a few more climbs.

In 2002, Barry Blanchard, Eric Dumerac, and Philippe Pellet established Infinite Patience (VI WI5 M5, 2,250m), reaching the summit via the Emperor Ridge. Then, in 2007, Steve House and Colin Haley climbed a variation left of the original Stump-Logan route (WI5 M8, 2,500m total), reaching the summit.

Jason Kruk and John Walsh established a new line to the Emperor Ridge (M6, 2,500m) in 2010, but didn’t continue to the summit in bad weather. In the spring of 2012, John Walsh and Josh Wharton made the first one-day ascent of Infinite Patience. In the autumn of the same year, Jay Mills and Raphael Slawinski completed the third ascent of the same line.

Leclerc goes solo

Leclerc had been dreaming of climbing the Emperor Face since he first saw pictures of it at the age of 10.

In 2016, at age 23, he felt strong enough to carry out his plan. From March 25 to April 11, he climbed four routes in the Valley of the Ten Peaks with his friend Luka Lindic, including three new ones.

“Each time we climbed another route, I could feel that my familiarity and confidence with the Rockies’ unique style of mixed climbing was becoming stronger,” Leclerc wrote.

In 2014, Leclerc had tried soloing Mount Andromeda’s Shooting Gallery route (also known as the North Ridge Couloir) and got scared, climbing “downward sloping frozen cubes of choss masked beneath six inches of powder snow.” He barely made it down. Now, he was ready to try again.

Leclerc climbs the first pitch on ‘Infinite Patience.’ Photo: Marc-Andre Leclerc

Leclerc didn’t own a car, so he hitched rides from Banff to Jasper and camped in hidden spots. He didn’t use a phone or watch, just an MP3 player for music. Before tackling Robson, he tested himself by soloing Mount Andromeda’s Andromeda Strain route.

“I marveled at how well the climb had gone and at how calm and comfortable I had felt soloing the route,” he wrote after. He was ready for the Emperor Face.

Leclerc’s Emperor Face

Leclerc took a bus to Mount Robson and spotted it from the highway. “The way it seemed to just tower above the road was like no other mountain I had seen; the summit felt incredibly distant, as if it were located on another planet entirely.”

He hiked 20km to Berg Lake, then skied to the Mist Glacier’s edge. There, he camped and looked at the Emperor Face, partly covered in clouds with wind howling high above.

“For the first time in a long time, I felt deeply intimidated by the aura of the mountain,” he said.

The next morning was calm. He skied up the moraine, then at the base, he put on crampons and got out his ice tools. He chose Infinite Patience and its gullies, chimneys, and ice runnels. The first ice pillar was steep and thin.

“The steepness took me by surprise and I had to stop to shake out several times through the crux section before the angle slowly eased off,” he wrote.

Deep snow slowed him in Bubba’s Couloir (named after Barry Blanchard), but he kept going, brushing away powder to find cracks for his tools.

“I would brush away large amounts of snow until finding an ideal thin crack, then I would use my other tool to gently tap the pick into place, creating a sort of self-belay.”

Frozen Berg Lake, toward the upper right of the photo, from two-thirds of the way up the face. Photo: Marc-Andre Leclerc

Soaked by snow mushrooms

Halfway up, he saw Berg Lake below. Near the top, snow mushrooms blocked the ice runnels. He tunneled through one, getting wet.

“I soon found myself scraping up a sketchy groove while digging a tunnel through the snow mushroom…I could not help but dislodge snow into my jacket and was soon soaked down to my base layer.”

Worried about getting too cold, he pushed on. The climbing improved on firm snow and mixed grooves. On a sunny ledge, he dried his clothes and made four liters of water, thinking the wind higher up might stop his stove. Two chimney pitches took him to the Emperor Ridge, where the views were phenomenal.

The 800m traverse across the west face was tough. For Leclerc, it was the physical and mental crux of the route.

“I kicked steps and planted my tools for what felt like an eternity, my gloves becoming wet and freezing solid in the cold wind.”

He reached the summit at sunset, his feet hurting badly. “Robson seemed to be so much taller than any of the surrounding peaks, like a platform in the sky looking down on the rest of the world,” he wrote.

On an upper ice section. Photo: Marc-Andre Leclerc

Descent and survival

After summiting, Leclerc chose to descend by the west face and the Emperor Ridge.

Leclerc was too tired to go down right away. He dug a trench in the summit snow and got into a thin bivy sack. He tried to stay warm with a hot water bottle, but the boiling water spilled, soaking him.

“I yelled an obscenity and realized that my situation was becoming too desperate to stay on the summit any longer.”

His headlamp batteries were dead, and his gear was covered in ice, but he started rappelling, using V-threads in the ice and leaving some gear behind.

At dawn, he reached a ledge and tried to melt snow, but his lighter fell down the mountain. With only 500ml of water left, he kept going, climbing down steep snow as ice fell around him. He saw the mountain’s shadow stretch across the horizon. He reached his skis, then skied to the river, eating food that didn’t need cooking. At Hargreaves shelter, he found a lighter, then realized he had a backup in his pocket all along.

Leclerc traverses toward the summit of Mount Robson. Photo: Marc-Andre Leclerc

Leclerc’s first solo of the Emperor Face was a huge achievement, but he didn’t tell the world about it. He lived simply, sleeping in stairwells, hitchhiking, and listening to music on his MP3 player.

After Leclerc’s climb, there were a few other excellent climbs on the Emperor Face. In 2018, Jasmin Fauteux and Maarten van Haeren repeated Infinite Patience, and in 2020, Ethan Berman and Uisdean Hawthorn established an amazing new mixed route, Running in the Shadows, up the right side of the face.

Marc-Andre Leclerc on the summit of Mount Robson at sunset. Photo: Marc-Andre Leclerc

Leclerc’s legacy

Tragically, Leclerc died in March 2018 at age 25. He and his climbing partner, Ryan Johnson, disappeared on Alaska’s Mendenhall Towers after climbing a new route. An avalanche likely took them, and their bodies were never found.

The 2021 documentary The Alpinist, directed by Peter Mortimer and Nick Rosen, details Leclerc’s incredible climbs and simple life. It features amazing footage and personal moments; the film captures Leclerc’s climbing philosophy.

This month, on October 10, Leclerc would have turned 33 years old.

You can watch the trailer for The Alpinist here: