Marek Holecek has responded bluntly on social media about the call for a rescue requested by Ondrej (Ondra) Huserka’s home team. He was there when his partner died, he explained. Any hope of finding him alive is just wishful thinking.

Below is Holecek’s account of the tragic accident on Langtang Lirung. After six days working on the first ascent of the east face, they successfully summited. So far, so good. Now they had to make it down.

Rescue useless

On October 31, around four o’clock in the afternoon, the following happened after we started downclimbing the wall.

I was rappelling from an Abalakov thread [a belay carved in the ice and snow] and Ondrej rappelled after me. What held fine for me proved fatal for him. The Abalakov thread cracked, and he fell into a crevasse.First, he hit an angled surface after an eight-meter drop, then continued down a labyrinth into the depths of the glacier. I rappelled down to him and stayed with him for four hours until his light faded. There’s nothing more to add.No rescue operation can revive what no longer breathes. Disinformation like ‘let’s save Ondra’ is nonsense. Anyone who participates in retrieving his body from such a wild place risks only one thing: increasing the number of grieving survivors.The only thing I’ll add is my gratitude to the 14 Summits Expedition agency, the Mammut team, and Francois Cazzanelli. They launched a rescue mission the very next day, as soon as they could. Helicopters flew, drones were deployed, and people on the ground were mobilized. However, nothing could change the outcome. The end is the end.

Francois Cazzanelli of Italy is an elite climber and a professional mountain rescuer from the Italian Alps. He was in the area as a member of a larger Italian team attempting Kimshung and Langtang Lirung.

The S.O.S. call

Ondrej Huserka and Marek Holecek before their summit push on Langtang Lirung. Photo: Marek Holecek

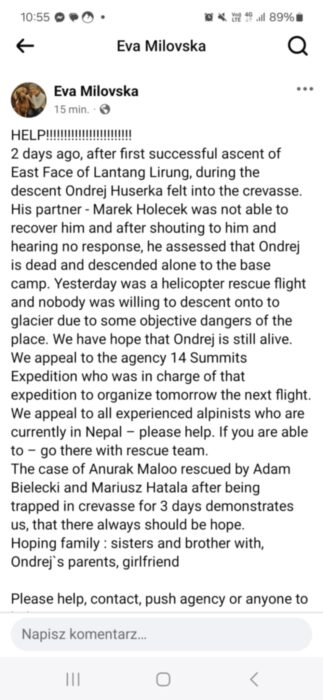

Early this morning, the climber’s partner, Eva Milovska, called for help, and friends of Huserka took up the call. Among others, they contacted Adam Bielecki of Poland. Last year, Bielecki rescued Anurag Maloo of India three days after he fell into a crevasse on Annapurna. Miraculously, Maloo survived.

SOS message from Huserka’s partner to Adam Bielecki

Bielecki shared the message on social media. He also contacted us at ExplorersWeb, and we passed on the message to Ukrainian climbers Mikhailo Fomin and Mykyta Balabanov, who were just down from setting a new route on Ama Dalbam. They immediately volunteered to help.

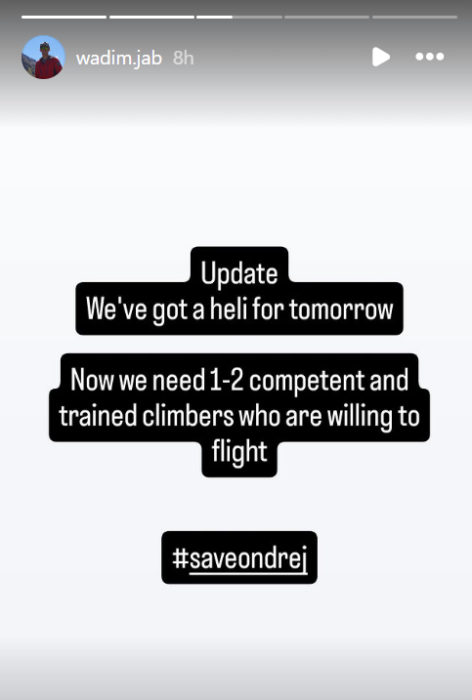

Meanwhile, Wadim Jablonski — Huserka’s former climbing partner — began coordinating a rescue.

“There must always be hope,” Jablonski posted, together with images from the rescue of Maloo, plus the following update on Instagram Stories:

On Saturday evening, just before Holecek revealed what had happened, the Ukrainians told ExplorersWeb they would likely not be asked to participate in any rescue if it did come off. The coordinating team would probably enlist Nepalese rescuers from Kathmandu instead. The Ukrainians continued to insist that they were ready to help.

It is currently the middle of the night in Nepal, and oddly, a rescue helicopter is scheduled for Sunday morning. The situation is confusing and unusual. Families of a deceased climber are told of the tragedy as soon as possible, but the call for rescue came from Huserka’s partner and friends, who are also climbers.

Details of Huserka’s death

Ondrej Huserka in Langtang some days ago. Photo: Marek Holecek

Holecek’s Facebook post explains what happened. The entire entry appears below, lightly edited for clarity.

I went for another of the many rappels that day. I set up what are called Abalakov anchors. Not complex — drill two intersecting holes at about 45° into the ice with a screw, creating an ice wedge. Thread a sling through, and voilà, the anchor is set, ready for another descent.

I slid down…[and] landed on a snow bridge between two deep crevasses. I continued, pulling the slack through my rappel device at my waist. When Ondra reached me, we’d pull the rope out of our last anchor and continue, trying to escape the wretched glacier. A completely standard process, without checking what was happening behind my back — because I couldn’t control it anyway.

Suddenly, I heard a grunt and strange sounds that my nervous system instantly processed as wrong — sounds that didn’t belong there. My heart skipped a beat. I yelled. No response. Again and again. My mind already knew what had happened. Only my soul hoped otherwise.

Unfortunately, the reality was clear — my rope disappeared into the depths of the glacier, where it shouldn’t have gone.

“Ondra!” I screamed, my voice raw. No answer. Long, cosmic seconds stretched before me, though surely it was less than half a minute. Suddenly, a voice called from the hellish hole: “Help, damn it, help!”

I didn’t think. I crawled to the edge of the crevasse, set the last ice screw into the wall.

“I’m coming for you, Ondra. Hold on!”

Without considering the consequences that would later prove nearly fatal, I wanted to reach him as quickly as possible. He was alive — it would be okay. As I descended, the light diminished. When I landed at the bottom, everything was dark. But I still wasn’t where the voice had come from. Ice shards began falling on my helmet from above, knocked loose by my rope, one giving my shoulder a sharp blow. Ignoring the pain, I continued.

The icy tunnel narrowed into a dark chute, robbing me of any visibility until I suddenly touched his hand. Contact…

Ondra screamed, “Pull me out, please.” Minutes passed in futile attempts. I tried, breathing heavily, pulling to no avail. The space was narrow, icy, and slippery. My mind couldn’t even conceive how [badly] he was wedged in there.

Finally, my thoughts turned rational. One thing preventing me from pulling him out was his backpack. I pulled a knife from my chest pocket and carefully cut his backpack open, tossing out the contents behind me down the ice chute — sleeping bag, gloves, jacket, and so on.

Then I felt a small hard object, which turned out to be a headlamp. Victory! I turned it on and put it on my head. At last, I could see. A small success. Then the horror set in—Ondra was wedged head down, with one arm trapped. Pulling his free arm was pointless. [But] I could make purposeful movements to free him.

In that tiny space, it took me around two hours to get him turned around. I know why it took that long. It was dusk when he fell, and now it was pitch dark, save for the narrow beam of light, as we fought on together.

Finally, I managed to pull Ondra onto me. Both of us were breathing heavily, exhausted.

“What hurts?” I asked.

“Nothing.”

Drunk with relief, my guard dropped. “Then let’s move, let’s climb out of this pit.”

His movements were oddly stiff. At first, I attributed it to the time he’d spent [stuck], until I understood: A broken spine and swollen eyelids I didn’t want to see spelled out the bad news…He couldn’t feel his legs, and his arms were paralyzed. His answers and awareness were totally confused…

His star was fading as he lay in my arms…it lasted hours.

How I got out of that hellhole and across the wild glacier the next day doesn’t matter… I’m here, and the one above who gave me this chance wanted me to be able to tell this story. In exchange, I’m burdened with the pain and images that I’ll carry to my last breath. I’m so sorry for Ondra, such a wonderful guy, a skilled climber, with a constant smile. Thoughts of self-blame haunt me — why him and not me? This pain is mine to bear…