Earlier this year, personnel from the Arctowski Polish Antarctic Station found human remains on King George Island’s Ecology Glacier. Now, DNA testing has confirmed that the body belongs to Dennis Bell, a British researcher who lost his life on the glacier in 1959.

Named for Polish scientist and Antarctic explorer Henryk Arctowski, the station was built nearly three decades after Dennis Bell’s death. Photo: Arctowski Polish Antarctic Station

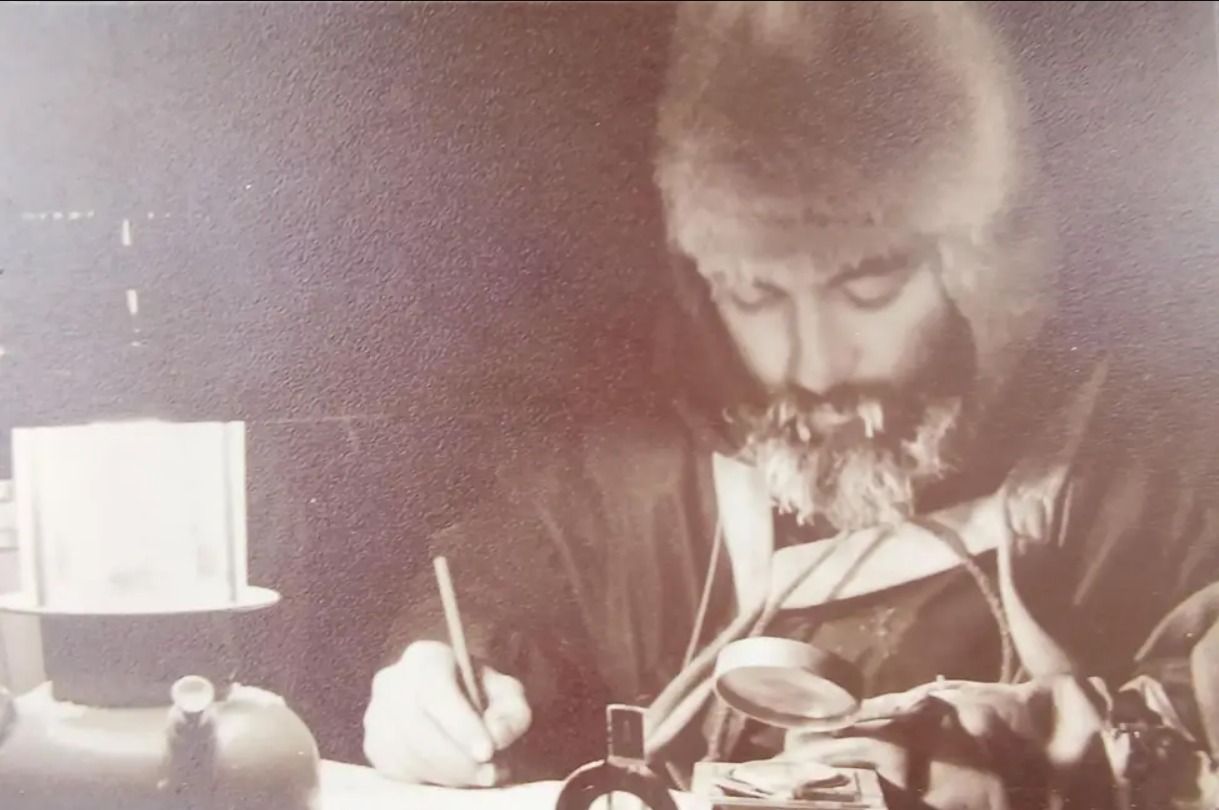

Dennis Bell in Antarctica

Dennis “Tink” Bell was born in London in 1936. After a spell in the Royal Air Force, he became a meteorologist. According to his brother David, Dennis was “obsessed” with the journals of Robert Falcon Scott. It’s no surprise, therefore, that Bell quickly joined the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey, which later became the British Antarctic Survey. In 1958, he arrived in Antarctica to begin a two-year residency on King George Island.

Though the station was isolated, and outside contact rare, records note that Bell was cheerful and fun-loving. While he was fond of joking, his teammates considered Bell a hard worker and the best cook in the hut. In addition to his meteorological duties, he took on the bulk of the cooking.

Bell, far left, and colleagues play with the dogs. Bell was especially fond of the sled dogs — allowed in Antarctica at the time — and helped raise two litters. Photo: British Antarctic Monument Trust

A tragic accident

Besides meteorology, his duties included surveying and mapping. On July 26, 1959, Bell was one of four who set out to map an unexplored section of the island. Bell and surveyor Jeff Stokes set out with a dog team half an hour ahead of Ken Gibson and Colin Barton.

Bell and Stokes were making their way up the glacier, forging a path for the later team. The snow was thick, and the dogs were tired, so Bell hopped off to run ahead and encourage the dogs. One moment, he was there, and the next, to Stoker, he was gone. Not wearing skis, he’d broken through a snow bridge over a hidden crevasse.

Stoker called out to him, and Dennis answered from nearly 30 meters down. Stoker lowered a rope and hitched the other end to the dog team. Dennis tied the rope around his belt and the dogs began to pull. But when he was nearly within reach, he was caught beneath the lip of the crevasse.

The dogs pulled, fighting the force of the solid ice, and Bell’s belt broke. In an instant, he plummeted back down the chasm. This time, when Stoker called to him, there was no reply.

Stoker ran back to Gibson and Barton as a storm was setting in. The trio searched for at least twelve hours through the near-blizzard conditions. They found nothing.

“It was a particularly tragic fatality which one really felt should never have happened, and thus doubly grievous,” Sir Vivian Fuchs, who later became the first Director of the British Antarctic Survey, said in his book, Ice and Men.

Dennis Bell worked in the Admiralty Bay Station Base G, shown here, which was demolished in the 1990s. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Rediscovery

After discovering human remains on the Ecology Glacier on January 19, Arctowski Polish Antarctic Station personnel marked the site. A month later, they returned with a team of experts in archaeology, anthropology, glaciology, and geomorphology. The researchers carefully unearthed bone fragments and artifacts. They then sent them back to the Falkland Islands via the research vessel Sir David Attenborough, and from there to the UK via the RAF.

In London, forensic geneticist Denise Syndercombe Court tested the human fragments. She compared DNA from the bone fragments with DNA from Dennis’ two siblings, Valerie and David. It was a match.

Dennis’ younger brother, David, was the one who answered the door on a fateful day in 1959. It was a telegram informing the family of Bell’s death. In an interview with the BBC, David admitted that their mother “never really got over” Dennis’ death.

The inconclusive state of his death, David felt, made it difficult for the family to move past. “There was no conclusion. There was no service; there was no anything. Just Dennis gone.”

“When my sister Valerie and I were notified that our brother Dennis had been found after 66 years, we were shocked and amazed,” David said. “Bringing him home…helped us come to terms with the tragic loss of our brilliant brother.”

Dennis Bell’s body emerged far from where he died. As the glacier moved and melted, his remains and personal belongings — including a pocket knife, wristwatch, and pipe — moved too. As glaciers continue to melt, we will continue to find missing remains; a grim silver lining to our planet’s changing climate.