For almost as long as people have been writing things down, they’ve been noting the strange and sometimes inexplicable things that happen around them. Eclipses, volcanic eruptions, unseasonable weather, and weird animal habits all appear in the historical records of civilizations around the world.

But of all the bizarre and disturbing things human beings have recorded, nothing excites the imagination quite like a storm of animals that definitely should not be falling from the sky.

If you’ve ever seen the movie Magnolia, you know a rain of frogs plays a significant role toward the climax of that film. But believe it or not, things like that really happen. And as far as we can tell, they’ve been happening pretty much since the beginning of recorded history.

An illustration showcasing a rain of fish recorded in Singapore. Illustration: Wikimedia Commons

Not quite cats and dogs

The list of animals that occasionally come pelting out of the atmosphere is extensive. Fish are by far the most common, but snakes, frogs, toads, jellyfish, worms, octopi, shellfish, and starfish have all been known to wreak havoc on umbrellas — or whatever the ancient Greek equivalent of an umbrella was.

“In Paeonia and Dardania, it has, they say, before now rained frogs; and so great has been the number of these frogs that the houses and the roads have been full of them,” wrote Greek philosopher Heraclides Lembus in the 2nd century B.C. A few hundred years later, Pliny the Elder also noted occurrences of fishy storms.

Historians tend to take ancient Greek and Roman philosophers with a grain of salt — particularly those philosophers reporting second or third-hand information. But in this case, it appears Lembus and Pliny were onto something.

How do we know? Because as history marched onward inexorably toward our present moment, the accounts kept stacking up.

An illustration of a snake rain dating to 1680. Illustration: Wikimedia Commons

A theory ahead of its time

Rains of fish and frogs in France and England in the 18th and 19th centuries had the Enlightenment-era scientists of the day scrambling for answers. In the early 1800s, French physicist Andre-Marie Ampere told the Society of Natural Science that frogs and toads can occasionally swarm in great numbers. He ventured that powerful storms might pick them up and deposit them elsewhere, sometimes in unexpected places.

As we’ll see, this explanation isn’t far from the current best theory held by modern scientists — though it doesn’t cover every occurrence as neatly as you’d hope.

For instance, in 1876, a Kentucky farm wife was making soap in her front yard when strange objects began falling down all around her. The first bizarre thing about this is that it was a cloudless day. The second, and infinitely more baffling thing is that the objects weren’t fish or toads or even *shudder* spiders — they were flakes of meat.

A newspaper at the time reported that “two gentlemen who tasted the meat expressed the opinion that it was either mutton or venison.”

Would you eat meat that fell from the sky? 1870s Kentuckians were built differently.

Later that year, a chemistry professor named Dr. L. D. Kastenbine published a paper speculating that the meat was the result of “disgorgement of some vultures that were sailing over the spot.”

Still, that’s just a guess, and scientists in the 1870s were no more able to prove it than we can prove that aliens exist.

The uncertainty is part of the fun.

A semi-serious search for answers

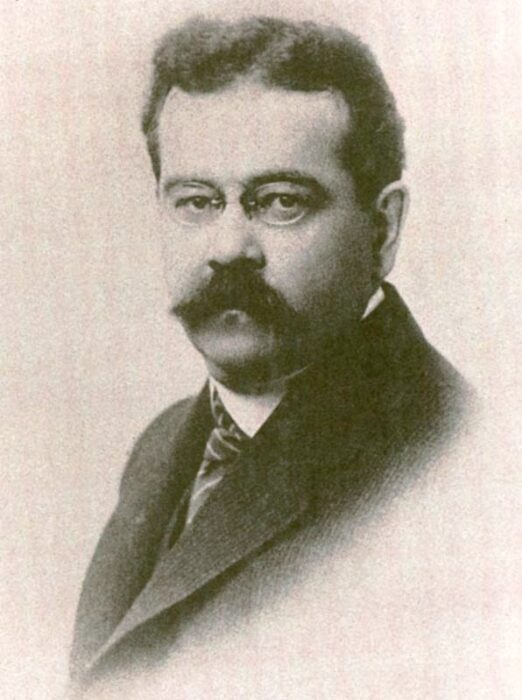

Enter Charles Fort, an impoverished journalist who struck lucky in 1916 when a rich uncle left him enough of an inheritance that Fort could quit the thankless newspaper business and pursue his own passions.

Before long, Fort was calling himself an “anomalistics researcher.” The one-time journalist carved out an interesting niche for himself. He collected accounts of strange phenomena — some verified, many others pure fabrications — and then invented truly ludicrous scenarios to explain them.

Fort covered a variety of topics in his four “non-fiction” books, but he was particularly interested in rains of animals. Using his journalism skills, he collected copious notes on the phenomenon and then set forth his theory.

Charles Fort: journalist, author, anomalistics researcher. Was he a satirist? Hard to tell. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

According to Fort, there’s a “Super-Sargasso Sea” floating in the atmosphere somewhere above the Earth. It’s a place where lost items and animals on Earth sometimes materialize and then rain down.

And that’s one of the tamer Fortian theories.

The curious thing about Fort is that no one at the time was sure if his work was satirical or meant to be taken seriously. A hundred years later, the verdict is still out, and probably depends on how willing you are to embrace the current crop of pseudoscientific theories. Certainly, all the ballpoint pens I’ve lost over the years have yet to fall out of the sky onto my head. Your mileage may vary.

Either way, Fort distrusted scientists and died in 1932 of debatable causes after refusing to visit a doctor during a period of failing health.

Modern explanations

Fort was on to this, at least — the periodic and random nature of animal rains makes them extremely difficult to study or even verify. But in the modern era, scientists have boiled it down to three plausible explanations.

The first is that heavy rains sometimes force large numbers of animals out of their burrows and hidey-holes while human beings are prudently taking shelter. Once the rains pass and people venture out into the sunshine, they notice, say, a field full of flopping frogs and naturally assume the amphibians got there the hard way.

The second theory is somewhat related — that flash floods caused by rains in other locations deposit animals in places they aren’t supposed to be, leading to similar assumptions.

It’s important to note that both these theories rely somewhat upon the tendency of human beings to make erroneous assumptions based on limited or circumstantial evidence. As a person on this planet, you’ve probably noticed this tendency in your fellow humans.

The problem is that every now and then, there’s a happening that can’t be explained away by pure human gullibility.

Yoro, Honduras

Take the small Honduran town of Yoro. Locals there claim they’ve been getting a scaley downpour once year for the last two hundred years or so in May or June. They’ve even created a local festival out of the phenomenon — the Lluvia de Peces, or Rain of Fish. Most researchers blew the happening off as a local superstition until a team from National Geographic observed it in the 1970s.

A fish’s eye view of the town of Yoro, Honduras. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

So, if animal rains are actually happening from time to time, what’s causing them?

Rather than simple wind storms à la Andre-Marie Ampere, scientists currently believe tornadoes or downspouts suck up animals both aquatic and terrestrial. These superstorms whizz them around in the clouds for a few minutes, and then splash them all over the heads of the good citizens of Yoro and other locations around the world.

It’s certainly plausible, and it fits what we know about how tornadoes work. But science has yet to overcome two small problems.

The first is that with very few exceptions, animal rains tend to comprise many individual animals of the same species. Animals like jellyfish, fish, and toads sometimes swarm. But if they were getting sucked up by a conveniently placed tornado, you’d expect to see some other species mixed in — very few natural ecosystems are completely homogenous.

The second problem is one that cuts to the core of the scientific method. To date, that we know of, no one has ever witnessed a tornado or downspout sucking up a group of animals.

Waterspouts like this one are probably responsible for some of the animal rain accounts throughout history. But the fact that scientists have never directly observed it happening is kind of wonderful. Photo: Shutterstock

Weird science

And it’s this fact that keeps animals rains squarely in the natural wonders column. We think we know why it happens. We think we understand the mechanisms and principles in place. But until we can observe and verify, we don’t know.

“I always find the frogs and the fish to be weird,” John Knox, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Georgia, told Smithsonian Magazine.

And if a man whose job it is to understand these things thinks it’s weird, there’s certainly room for you and me to appreciate the strangeness of the phenomenon — even if the cause is probably known.

One thing’s for sure. It’s happened before, and it will happen again. For not the first time in history, it’s about to start raining…well, you call it.