The Chihuahuan Desert is a sparse but stunning ecosystem straddling the border between Northern Mexico, Southern New Mexico, and West Texas. High in elevation and low in humidity, the desert plays home to spiky ocotillo plants, blinding dust storms, and fragrant green chili farms.

In the cool evenings, coyotes, antelope, and ringtails play out the timeless drama of desert survival. Kangaroo rats scamper beneath the creosote bushes, licking dew off the leaves and hoping not to be ambushed by rattlesnakes. The sunsets are spectacular.

But the wonders of the landscape don’t stop at the surface. Far underground, another awe-inspiring treasure awaits.

A quarter-of-a-century ago, two brothers drilling a ventilation shaft for the Naica Mine in Chihuahua, Mexico, stumbled across something fantastic. The miners were working 300m underground when they broke into a basketball-court-sized cavern filled to the brim with the largest crystal formations they’d ever seen.

The Cave of Crystals. Photo: Penn State University

What their lights illuminated would come to be called “The Cave of Crystals,” and it’s as deadly as it is beautiful.

11m crystals galore

As the brothers shone the first light into the cavern, they saw a tangled maze of huge selenite crystals that almost defy words. The largest is 11m long with an estimated weight of five tons, but all of them are huge. The crystals are a milky, translucent white. Their sheer scope and maze-like formation — combined with manmade light — create an otherworldly effect that tends to leave observers temporarily speechless.

“There is no other place on the planet where the mineral world reveals itself in such beauty,” Juan Manuel García-Ruiz, a geologist at the University of Granada, told National Geographic in 2007.

García-Ruiz was part of a team intent on discovering how the natural wonder formed. To do so, he studied tiny pockets of water trapped inside the crystals. What he and others uncovered involves magma, as so many of the planet’s best spots do.

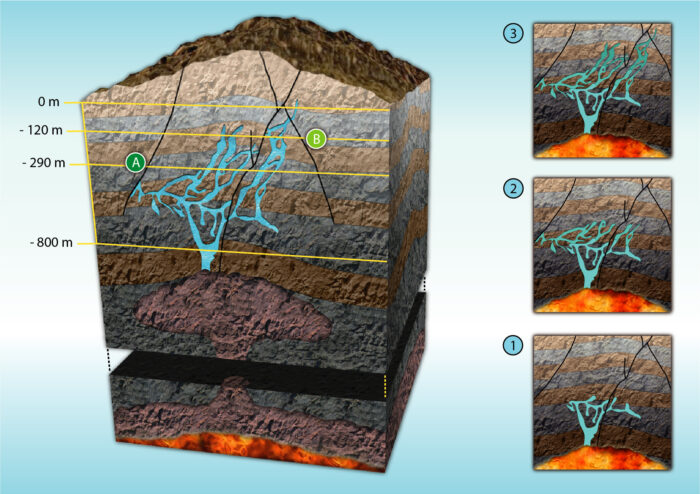

Roughly 4km below the Cave of Crystals is a large pool of magma that radiates a constant heat. At some point in the distant past, the cave was flooded with water rich in a mineral called anhydrite. For a million years, the magma kept the water at a constant temperature of 58°C, allowing the anhydrite to dissolve into gypsum. Gypsum likes turning into selenite crystals, and so, firmly in their sweet spot, they did just that.

Graphic: Albert Vila and Andreu Módenes, University of Barcelona

Eventually, the water drained out of the cavern (thanks to water pumps elsewhere in the mine), leaving behind a maze of crystals.

Beautiful death

The Cave of Crystals comprises at least four chambers: the Cave of Crystals, the Queen’s Eye Cave, the Candles Cave, and the Ice Palace. The qualifier “at least” is there because 25 years after its discovery, the cavern system has yet to be fully explored.

That’s because while the caves are friendly to crystal formation, they aren’t necessarily friendly to human survival.

Temperatures inside the caverns can get up to 58°C, near record-setting temperatures in Death Valley. But as the old saw goes, it’s not the heat that gets you, it’s the humidity. In the Cave of Crystals, humidity can reach a whopping 90 to 100 percent.

Those conditions will kill you, and it doesn’t take long.

So, when the first scientific explorations commenced, they required a little engineering first. A team led by cave mineral specialist Paolo Forti, of the University of Bologna, developed special refrigerated cave exploration suits before venturing forth.

The team started with standard cave exploration overalls, then added a thick tubing layer connected to a backpack. The backpack held 20kg of water and ice, which was then pumped through the tubing. Add a refrigerated respiration system, and you’re all set to explore the Cave of Crystals. For a few minutes.

It takes specialized equipment to explore the Cave of Crystals. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The system, though sophisticated, only keeps you cool for about thirty minutes at a time.

Another hurdle the team had to jump was the crystals themselves. Take a glance at photos from the Cave of Crystals and you’ll see just how physically demanding it must be to navigate them. Exploration indicates more chambers, but that would mean destroying some of the crystals blocking the (prospective) openings, something no one involved is willing to do.

A window closes — for the best?

Operations ceased in the Naica Mine in 2015. With the pumps turned off, the caves reflooded, halting further scientific exploration.

But the discoveries made in the brief 15-year window were significant. Ancient pollen experts, geochemists, geologists, and hydrogeologists all had a chance to study the stupendous formations.

Interestingly enough, biologists also had a field day. They hoped that as the crystals formed, they trapped DNA from ancient bacteria swimming around in that million-year-old hot water. At first, they came up dry, but in 2017, speleologist and extremophile expert Penelope Boston from the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology announced a discovery. She had discovered ancient bacteria embedded in a few of the crystal samples taken before the caves reflooded.

The bacteria are unique and don’t resemble anything currently known to science.

For now, the caves will remain closed to human exploration, though that might change if operations in the mine resume. In the meantime, while those of a scientific bent might mourn the loss of the knowledge hidden in the crystals, we can at least take solace that the Cave of Crystals has returned to the same state we found it in — a rare thing to be able to say.