The Spanish word ‘penitente’ translates as remorseful. It refers to the Catholic tradition of getting on one’s knees and begging for forgiveness. Deep in the Atacama Desert, you will find tall, thin blades of snow that resemble hundreds of penitent worshipers kneeling on the desert floor.

Penitentes at night. Photo: ESO/B. Tafreshi

In the 1830s, Charles Darwin was traveling from Santiago, Chile to Mendoza, Argentina when he stumbled upon these thin blades of snow. He wrote, “Frozen masses, during the process of thawing, had in some parts been converted into pinnacles or columns, which, as they were high and close together, made it difficult for the cargo mules to pass.”

Penitentes are rare high-altitude snow formations that usually occur above 4,000m. The pointed blades of snow measure up to five metres long and are always oriented toward the sun. They appear in big clusters on the slopes of the Andes and in other parts of the Atacama Desert. Penitentes can form year-round.

Why do they form?

There are several possible explanations. The most widely accepted is the process of sublimation. This is when the sun’s heat turns the snow directly into water vapor, skipping the melting process. Sublimation causes a snowy surface to develop depressions, troughs, and crevices which eventually leave large pointed spikes. The vapor moves up which gives the snow ridges their pointed shape.

Some scientists claim that heat from the sun could be trapped. The water vapor would then diffuse away from the ice, creating spaces between the icy blades.

A field of penitentes on a mountainside. Photo: DreamX/Flickr

In the Journal of Glaciology, G.C. Amstutz postulated that a variety of processes and variables form penitentes. These include consistent temperatures, erosion by wind and dust, changes in humidity, and the amount of snow present. Experiments with ice in a controlled lab setting found that penitentes formed on a block of ice at temperatures of -4°C and below when humidity was below 70%.

Penitentes up close. Photo: reisegraf.ch/Shutterstock

Red patches

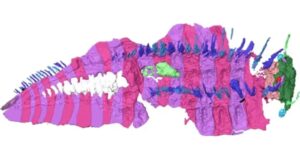

A seemingly unlikely place for life, penitentes house snow algae. Snow algae are microorganisms that can sustain themselves in extreme environments. Since penitentes also exist on Pluto and on the moon Europa, this Andean phenomenon may be a fertile topic for astrobiological research.

As you wander through the fields of white pinnacles, you can observe the snow algae in small patches of red, hidden in the nooks and folds. A 2018 study by Lara Vimercati showed that these red patches house algae of the Chlamydomonas and Chloromonas groups. They are similar to those present in polar regions. According to algal physiologist Matthew Davey, the algae might have arrived via the wind or animals. Because of the ice melts so slowly, the continued presence of a little water is enough for the algae to grow.

The algae’s red color comes from a substance called carotenoid, a natural red pigment found in algae, bacteria, and certain species of plants. This pigment gives orange vegetables, shrimp, and flamingos their bright color. Researchers believe that the red color shields the algae from the sun’s harsh rays and from frigid temperatures.

These red algae that grow on snow are familiar to most people who explore snowy environments. While sometimes they exist only in small patches, they occasionally color broad areas. In 1818, arctic explorer John Ross, the first European to visit Northwest Greenland, saw a headland that he famously called the Crimson Cliffs, painted by this algae.

Artist Charles Hamilton Smith’s rendering of the Crimson Cliffs of Northwest Greenland.