I’m a severe claustrophobe. After getting trapped in a slide in my local McDonald’s at five years old, I swore off all tight and dark spaces forever. So it’s not entirely surprising that I couldn’t get the images of rushing, rising water and tunnels almost impossible to squeeze out of my mind when reading about an expedition to Veryovkina Cave in National Geographic.

This dramatic escape from death took place in September 2018. A Russian expedition, accompanied by two British cave photographers, descended into the depths of one of the world’s deepest caves in the remote Gagra Mountains of Abkhazia in the Caucasus. What was meant to be an exciting venture to further map and determine the cave’s depth and to evaluate life in extreme conditions turned almost fatal when a dangerous flood threatened to drown the explorers. Because of this, many believe it is one of the most dangerous caves in the world.

Background

Veryovkina Cave is located in the Arabika Massif, which is part of the Greater Caucasus Mountain Range and extends across several countries, including Russia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains were formed primarily due to the collision between two tectonic plates, the Eurasian Plate and the Arabian Plate.

The Arabika Massif itself formed during the Miocene Epoch when the Eurasian Plate moved south and pushed against the Arabian and African Plates. The rock that was being folded, uplighted, and faulted was predominantly limestone.

Over millions of years, rainwater, slightly acidic due to dissolved carbon dioxide, has slowly eroded the limestone of the Arabika Massif, forming an extensive karst landscape containing some incredibly complex and deep cave systems, sinkholes, and long underground rivers. The Arabika Massif has four of the world’s deepest caves: Krubera-Voronja, Veryovkina, Sarma, and Snezhnaja.

Water starts to flow through the passages of the cave. Photo: Petr Lyubimov

It wasn’t until 2018 that the cave really started to make waves in the spelunking community. Why was this?

Though Veryovkina Cave is the second deepest at a whopping 2,212m, its discovery was a complete accident. Let’s begin at its entrance: a rather small and unassuming hole in the ground.

The slow descent

The exploration of Veryovkina Cave proceeded slowly. It took over 50 years and 30 expeditions to fully determine its depth. In 1968, cavers from Krasnoyarsk, Russia, found the cave’s entrance, a tiny cross-section measuring three by four meters. Though they managed to descend to 115m, they had absolutely no idea how far this subterranean monster went. Almost two decades later, from 1982 to 1986, members of Moscow’s Perovo Speleoclub made several expeditions and slowly but surely pushed to a depth of 440m. Then came the fall of the Soviet Union and all the turmoil as people tried to survive hyperinflation and their new reality. It wasn’t until 2000 that expeditions started back up again.

From 2000 to 2016, the Perovo teams continued to do small expeditions, finding new shafts and new passages and eventually pushed to a depth of 1,350m. In 2017, they got to 2,151m and happened upon 17km of horizontal tunnels and passages.

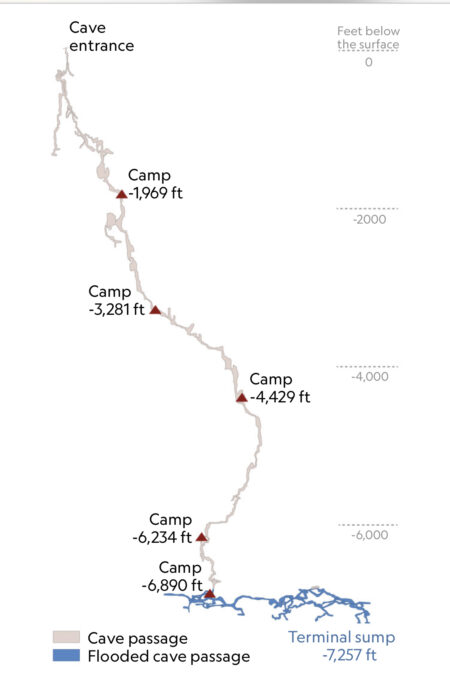

Because of the extreme depth and to make exploration easier and safer, a permanent multi-camp system has been set up, much like how it is on Everest each spring. Camp One is on the surface, Camp Two is at 600m, Camp Three at 1,000m, Camp Four at 1,350m, Camp Five at 1,900m, and Camp Six at 2,100m. There is also a cable system for communication. At the bottom, there is a turquoise lake 28m deep. To reach it takes roughly four days and eight hours between each camp.

Exploring Veryovkina Cave is a perilous undertaking due to its extreme depth, narrow passages, and unpredictable conditions. Temperatures drop below freezing, and humidity is 100%.

2018 to 2021

The cave gained international notoriety from 2018 to 2021, when two major incidents occurred. In September 2018, the Russian Perovo Speleo cavers returned there. Its members were Pavel Demidov, Petr Lyubimov, Konstantin Zverev, Andrey Shuvalov, Evgeniy Rybka, Andrey Zyznikov, Roman Zverev and Natalia Sizikova. Also tagging along were well-known cave photographers Robbie Shone and Jeff Wade. Though the photographers were not as experienced with a cave of this magnitude, they knew how to hold their own.

A diagram showing the Veryovkina Cave network. Photo: Gaia Dempsey/X

The expedition went according to plan. On day seven, they were making breakfast. Two members, Roman and Natalia, had to leave early to get to the airport for a flight. However, everything took a dark turn. The team noticed water starting to pour into the cave because of a storm on the surface.

This wasn’t just a trickle, it was a flood pulse. A flood pulse refers to a temporary increase in the flow of water within a cave system, typically caused by heavy rainfall, snowmelt, or upstream flooding in a connected underground river or stream. This pulse of water can lead to the temporary flooding of passages, chambers, and subterranean water features within the cave. Alarmed, they sent a message to the team below via their cable system. The flood pulse would take 30 minutes to reach the bottom.

At first, the Russians seemed unbothered by the waterfall starting to form, although the sound of its approach shook the cave and was like thunder. However, they’d experienced similar flood pulses many times, and they do not usually last long or turn deadly. Their camp was a decent distance from the water, anyway. However, this calm demeanor changed to terror within a couple of minutes.

Veryovkina Cave. Photo: Facebook

‘His white face said it all’

In Robbie Shone’s article for BASE Magazine, he described what happened next:

The water rose so fast it was impossible to tell how quickly it was rising. Petr checked the hole once again, and as he turned around his white face said it all. The three-meter-deep hole was now full of surging, rising water…

…the most enormous torrent of white water appeared out of this hole, and I just stood opened-mouthed at the sight of this huge white wall of water entering out little home.

The water table was rising so fast that they had little time to pack their gear and hurry to the vertical ropes.

“One must have an extremely high level of physical endurance to ensure a sufficient margin of safety. When something goes wrong in a very deep cave like Veryovkina, you need to act fast. It’s crucial that you haven’t used all your reserves up just getting to the bottom of the cave. In mountaineering, the most dangerous part of the climb can be the descent, and in a big cave the most challenging part can be getting out again.”

They took only essential equipment and had no choice but to leave expensive, heavy equipment behind. The passages, chambers, and bridges they crossed previously were now underwater. Robbie Shone and Jeff Wade climbed up the vertical shaft first. The whitewater poured over their heads and they were barely able to breathe. They ascended agonizingly slowly but managed to get to an outcrop beside the flow of water. Thankfully, the Russian team met up with them, and the expedition made it out alive.

A 2020 victim

Veryovkina did not claim anyone’s life that day but eventually did in 2020. In November, hikers found a rope and personal effects at the cave’s entrance. Entering the cave without permission is not allowed. Suspecting someone was down there, a group of cavers contacted the authorities, then descended to investigate. They found a decomposed body hanging from the rope at around 915m.

In August 2021, they recovered and identified the body as Sergei Kozeev, an adventurer from Russia. An avid outdoorsman, Kozeev had said goodbye to his family to go on an expedition. As usual, he did not tell them where he was going. Then one day, he didn’t come home. A missing person’s report was filed, and even after the body was found, it took months for authorities to make out what had happened. They determined that he ran into difficulties, could not move, and eventually died of hypothermia.

Note that Veryovkina is not the deepest cave in this challenging system. Its sister cave, the Krubera-Voronja, is deeper still, at 2,256m.