It’s New Zealand in 1887. Two men push an unsteady raft into a stream, just where it vanishes into a rift in the Earth. Opaque water laps at the edges of the raft as they venture into the twilight zone of the cave’s entrance. Above their heads, the ceiling closes in. Behind them, the light of day gradually leaches away.

They light a candle and paddle on.

The two men are Tane Tinorau, a local Māori leader, and Fred Mace, an English surveyor. Māori people had known about the cave’s entrance for generations but left it unexplored because, to them, it represented the entrance to the underworld.

But now, at the tail end of the 1800s, it is being explored — not by a team sporting modern SCUBA equipment, safety lines, and electric lights, but by two brave men paddling into the unknown, boasting only bravery, a candle, and a homemade raft.

Eventually, Tinorau and Mace drift to a series of chambers where something unusual catches their attention. On the cavern roof, a glimmer of blue-green shimmers slightly before fading in the candlelight.

Perhaps the two men exchange glances. They blow out the candle and wait.

And then, slowly at first but then with increasing intensity, the world lights up again.

On the cave ceiling, hundreds of bioluminescent larvae ignite. Their unearthly light reflects on the still water beneath them, shines through the strands of beaded silk hanging down from the roof, and illuminates the awe-struck faces of the two explorers.

Introducing the New Zealand glowworm

Arachnocampa luminosa, the New Zealand glowworm, is a species of fungal gnat. But that’s like saying a snowflake under a microscope is “merely some frozen water” or a painted bunting is “a fancy-looking cardinal.” If there’s one thing even a passing study of the planet tells us, it’s that natural wonders are endless in their variety, sometimes occurring in the smallest and most unassuming of animals.

Such is the case with the New Zealand glowworm. First observed by Europeans in a gold mine in 1871, the larvae were initially thought to be a form of invasive glowing beetle imported by colonists.

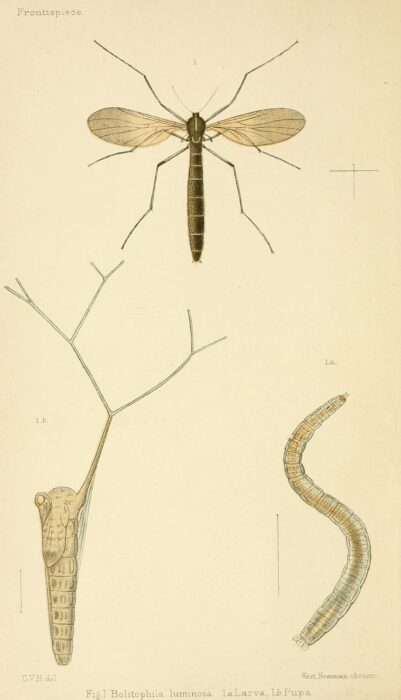

Illustration of the life cycle of Arachnocampa luminosa, taken from the Elementary Manual of New Zealand Entomology, published in 1892. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It wasn’t until 1886 that an enterprising teacher in Christchurch showed the sparkly little animals were gnat larvae. The species waited another five years until it was formally described by science. Since then, glowworms have been observed all over New Zealand, not just in caves. Some enterprising fungal gnats even manage to reproduce in the bushes above ground. Still, most of the bright little gnats prefer the safety of the deep dark.

A. luminosa lays its eggs directly on the surface of cave walls. After the eggs hatch, the larvae spin delicate threads, periodically beaded with bulbs of sticky, insect-trapping silk. Then, deep in their abdomen, the larvae secrete a unique luciferase enzyme, which interacts with a small molecule of luciferin. The biochemistry is similar to that used by fireflies, although the precise mechanism and chemical makeup are unique to A. luminosa.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

As the larvae begin to glow, so too do their silk strands — all the better to lure small insects to their deaths. When hundreds of larvae and strands illuminate, it produces a striking visual effect that produces wonder in all but the most jaded observers. The night sky is reproduced deep underground, the quiet dark transformed into a reflected microcosm of the heavens.

Who owns the Waitomo Glowworm Caves?

Tane Tinorau was certainly struck by the power of the Waitomo Glowworm Caves, and he had a hunch others would be as well. After another exploration with Mace in 1888, the Māori began developing plans to lead other travelers into the caves.

By 1889, Tinorau and his wife Huti were guiding tourists through for a small fee. Five hundred people visited in the first two years, and it looked as if Tinorau had latched upon a money-making scheme that provided autonomy and independence to a people often hamstrung by white colonists.

A close-up of the sticky silk strands New Zealand glowworms use to capture their prey. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The colonial government of New Zealand had other plans. Thomas Humphries, Commissioner of Crown Lands and Chief Surveyor of Auckland from 1889 to 1891, surveyed the caves and noted that graffiti had already started appearing on the delicate limestone formations. Although he noted that “the natives are now taking great care of the caves,” he still recommended the government take control.

The only problem (from New Zealand’s perspective) was that Tinorau and his family refused to sell. In the time-honored tradition of government authorities everywhere, the movers and shakers in New Zealand didn’t let that stop them. Using legislation passed in 1903 and 1905, the New Zealand government wrested control of the caves from the Māori in 1906. Tinorau and his family were given £625, about five years’ worth of wages for a single skilled tradesman.

Correcting a wrong

The Waitomo Glowworm Caves continued to grow in popularity. Under New Zealand’s ownership, infrastructure — including a hotel built in 1910 — continued to crop up on the site. The caves and surrounding property changed hands again in 1990, going to the privately held (but not by Māori) Southern Pacific Hotels Corporation.

Along the way, several other important discoveries were made, including cave art, incredible limestone formations, and the bones of a moa — a now-extinct flightless bird that once called New Zealand home.

‘The Cathedral,’ a limestone formation in the Waitomo Glowworm Caves. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“It wasn’t until people went caving and found these bones that we realized the extent of wildlife extinctions in New Zealand after human arrival. It’s what you find in caves that really gives us a window into the past,” Waitomo Glowworm Caves guide Logan Doull told National Geographic Traveler in 2023.

Then, finally, in 1994, some form of justice. Following years of pressure, a joint venture by New Zealand’s Department of Conservation and the descendants of the area’s original Māori inhabitants now run the operation.

The caves today

And quite the operation it is. Visitors to the caverns can explore them by boat or while floating on an inflatable tube. While it’s possible to access the caverns via a beautifully rendered winding staircase, adventurous sorts can enter via rappelling and zipline, providing a jolt of adrenaline before experiencing the spectacular bioluminescence.

Thanks to a partnership between the Maori and the New Zealand Department of Conservation, the Glowworm Caves can be enjoyed without harming the native species. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The story of the Waitomo Glowworm Caves touches on many of the most important conservation issues of the day — the intersection of tourism and science, the protection of the planet’s natural wonders, and who, exactly, gets to administer those wonders.

Through it all, the little fungal gnats of the Waitomo Glowworm Caves keep glowing. We’re lucky to have found them and even more lucky to have kept them.

And it all started with two brave men and a single candle, extinguished in the dark.