New research conducted at the site of the Roman baths in Bath, England, seems to back up the long-held belief that the waters there could do more than relieve achy joints and promote relaxation. They might legitimately hold healing properties.

In the journal The Microbe, researchers from the University of Plymouth’s School of Biomedical Sciences revealed that at least 15 of the microorganisms swimming in Bath’s world-famous waters produce antimicrobial compounds that could help combat some of humanity’s most vicious microscopic enemies: E.coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Shigella flexneri, to name three of the most prominent.

The waters at Bath are chock-full of antimicrobial goodness. Photo: Shutterstock

“This is a really important and very exciting piece of research,” Dr. Lee Hutt, Lecturer in Biomedical Sciences at the University of Plymouth and lead author on the paper, told ScienceDaily. “The waters of the Roman Baths have long been regarded for their medicinal properties…Now, thanks to advances in modern science, we might be on the verge of discovering the Romans and others since were right.”

Science meets tradition

Everyone — including animals from capybaras to snow monkeys — enjoys a hot spring, but no one loved to get their soak on better than the ancient Romans. The Romans started dipping in Bath sometime between 60 and 70 AD, though native Britons almost certainly used the springs long before the invaders arrived.

Regular soaking continued until the Roman Empire withdrew from Britain in the fifth century AD. The Romans who stayed around (not to mention Romanized Britons) kept up the practice for a while, though the facilities were in ruins by the sixth century, according to a chronicle penned during the reign of Alfred the Great, another couple of centuries down the road.

Soaking enthusiasts in the early and late Middle Ages rebuilt the site, and the waters of Bath have been a tourist attraction ever since, renowned for their healing abilities. Until now, those legends have been purely anecdotal.

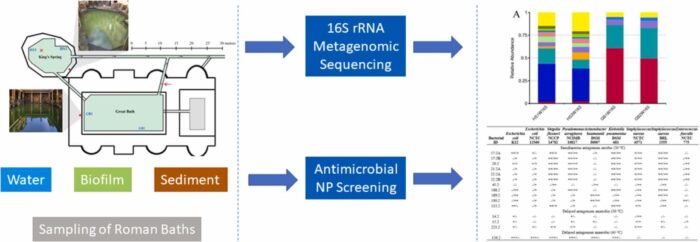

Enter the scientific method. Scientists collected biofilm, water, and sediment from two locations in the baths. They then analyzed the samples using gene sequencing technology and tried-and-true culturing methods. The scientists isolated 300 types of bacteria from the samples, 15 of which packed enough antimicrobial punch to warrant further study.

An image from the paper showcases the types of samples collected from various points at the baths and how they were sequenced. Illustration: Lee P. Hutt et al.

More work to do

The team stressed that more work is necessary before the organisms at Bath can be used to combat the estimated 1.25 million deaths that occur annually due to antibiotic-resistant bacteria. However, the initial study was promising enough that the University of Plymouth will expand the research beginning this fall.

So the next time someone tells you a hot spring may have healing properties, don’t immediately roll your eyes. Do the smart thing and make like a macaque.

Science finally proves what snow monkeys already knew — soaking is great. Photo: Shutterstock