Earlier, we published a deep dive on how to interpret climbing grades. As a quick reference, here are the key points from that story. This will help you sort out the differences between the likes of 5.13b, 8a+, WI3, and M9 when they appear in ExWeb articles.

Simply put, a climbing grade describes the difficulty of the terrain on the route. These grades help other climbers judge whether it is suitable for their level.

But what goes into climbing grades, and why do they involve so many letters and numbers? Climbing is rife with technical jargon, and trying to decode the abbreviations can seem daunting. Let’s take a look at the basics.

Who Sets a Grade?

Climbing grades are subjective, so the difficulty of a climb is established by consensus. The first ascensionist, or first ascent team, gets the first crack at grading the route. After that, several other climbers generally weigh in (once they have completed it). Eventually, they reach a consensus.

Glossary of Terms

- Route: the full length of a rock climb, from the bottom to the top.

- Anchor: any device (like bolts, pitons, etc.) that attaches a rope or climber to the climbing surface.

- Pitch: the distance between two anchors on a route that’s longer than the rope. For instance, you can climb a 200m route in three pitches with a standard 70m rope.

- Free Climbing: using only one’s hands and feet, and the natural features of the rock, for upward progress.

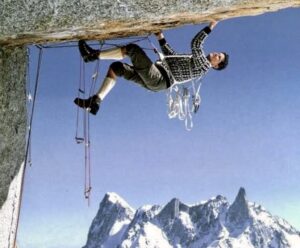

- Aid Climbing: pulling or standing on gear attached to the rock for upward progress.

The most prominent grade systems are:

- French Numerical System (6b+, 8a, etc.)

- YDS, or Yosemite Decimal System (3rd Class, 5.5, 5.11b, etc.)

- Commitment grade (III, VI, etc.)

- Aid rating (A2, A3+, etc.) or Clean Aid rating (C2, C3, etc.)

- Mixed grade (M4, M5 etc.)

- Water Ice grade (WI4, WI5+ etc.)

- Alpine System (F, ED, etc.)

Of these, the two most common ways to grade a climb are the French Numerical System and the Yosemite Decimal System.

A 7a+ climb in Thailand.

French Numerical System (FR) — 6a, 8b+, etc.

The French Numerical System (FR) is the dominant grading system for free climbing outside North America. ExplorersWeb’s contributors typically use FR when discussing technical ratings in articles.

FR rates a climb according to the overall technical difficulty and strenuousness of the route. Grades start at 1 (very easy) and the system is open-ended. Grades 5 and higher can be further distinguished with the addition of a lowercase letter: a, b, or c. As well, a “+” may be added to indicate more sustained difficulty (6a+ is harder than 6a, but easier than 6b). Currently, the hardest route in the world is graded 9c.

The thin holds of a 5.11 climb.

Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) — 5.6, 5.11a, etc.

YDS is the dominant classification system in the United States and parts of Canada.

Developed by the U.S.-based Sierra Club in the 1950s, the YDS unified and refined previous systems from the early days of Yosemite Valley climbing. The YDS is subdivided into five classes according to technical difficulty.

Classes 1 and 2 relate to hiking and trail running; classes 3 and 4 designate easy scrambling up slightly inclined terrain, and Class 5 describes technical rock climbing.

Class 5 ratings start at 5.0, which describes a low-angle incline requiring minimal skills. 5.15 is currently the top end. The official description for 5.15 terrain is “exceptionally difficult, often involving steep or overhanging rock that requires elite expertise, physical conditioning, and technical acumen.” Only elite climbers can manage 5.15.

Climbs rated 5.10 or harder may also carry a letter from a to d. For example, a route or pitch rated 5.10a is easier than a 5.10b. A 5.13 is harder than a 5.12d but easier than a 5.13a, etc.

Note that a route’s technical difficulty does not determine the objective risk to the climber. The risk depends on various factors, including the quality of the hardware and the rock, and runout (the space between anchors or gear placements).

NCCS commitment grades — III, VI, etc.

In the U.S. there is also a system that measures the “commitment” required for a route. The National Climbing Classification System (NCCS) bases time commitments on how long an average climbing team will be on the route.

- I: one to three hours

- II: three to four hours

- III: four to six hours

- IV: a full day of climbing, often mildly technical (usually eight to 12 hours)

- V: requires one overnight

- VI: two or more days but less than a week total

- VII: a long and major big wall expedition, usually in remote locations and lasting a week or longer

Other grading systems

Free climbing isn’t the only type of climbing that can be measured for difficulty. Ice and mixed climbing also require ratings and use similar systems. We will briefly cover these two disciplines below, but for more information, you can check out our in-depth explainer here.

Ice climbing is exactly what it sounds like — climbing up pillars or walls of ice, usually from seepage or frozen waterfalls. Climbers use ice axes, crampons, and specialty ice screws to get the job done.

Sometimes, the ice runs out and leaves the climber with bare rock. When an ice climber uses their crampons and axes to climb on rock, it’s called dry tooling. The style of swapping freely between dry tooling and ice climbing depending on the terrain is called mixed climbing.

A potential mixed route, where the climber may move from ice to rock and back to ice again.

Water Ice climbing grades — WI3+, WI6, etc.

- WI1: Low angle ice; no tools required.

- WI2: Consistent 60º ice with possible bulges; good protection.

- WI3: Sustained 70º with possible long bulges of 80º-90º; reasonable rests and good stances for placing screws.

- WI4: Continuous 80º ice fairly long sections of 90º ice broken up by occasional rests.

- WI5: Long and strenuous, with a rope length of 85º-90º ice offering few rests or a shorter pitch of thin or bad ice with protection that’s difficult to place.

- WI6: A full rope length of near-90º ice with no rests or a shorter pitch even more tenuous than WI5. Highly technical.

- WI7: As above, but on thin, poorly bonded ice or long, overhanging, poorly adhered columns. Protection is impossible or very difficult to place and of dubious quality.

- WI8 and above: Amounts to hard bouldering on a rope, using ice tools and crampons, often with bolts as protection.

Mixed climbing grades — M1, M8, etc.

Mixed terrain grades go from M1 (low-angle terrain that usually requires no ice axes) to M12 (steep terrain with gymnastic moves on tenuous holds). Routes graded M13-16 exist, but difficulty within that range is considered conjectural.

- M1-3: Easy. Low angle; usually no tools.

- M4: Slabby to vertical with some technical dry tooling.

- M5: Some sustained vertical dry tooling.

- M6: Vertical to overhanging with difficult dry tooling.

- M7: Overhanging; powerful and technical dry tooling; less than 10m of hard climbing.

- M8: Some nearly horizontal overhangs requiring very powerful and technical dry tooling, bouldery or longer cruxes than M7.

- M9: Either continuously vertical or slightly overhanging with marginal or technical holds, or a horizontal roof with plentiful tool placements of two to three body lengths.

- M10: At least 10m of horizontal rock or 30m of overhanging dry tooling with powerful moves and no rests.

- M11: A rope length of overhanging gymnastic climbing, or up to 15m of roof.

- M12: M11 with bouldery, dynamic moves, and tenuous, technical holds.

- M13-M16: Conjectural. The world’s hardest mixed route, by Will Gadd and others at Helmcken Falls, BC, Canada, is ungraded.

Alpine climbing grades

The alpine system is a simple method of describing difficulty for, you guessed it: alpine routes. The ratings measure several variables: climbing difficulty, remoteness, altitude, danger, and commitment all factor in. While it could be seen as a bit archaic, it’s gaining popularity for its simple utility.

- F: Facile/easy. Rock scrambling or easy snow slopes; some glacier travel; often climbed ropeless except on glaciers.

- PD: Peu Difficile/a little difficult. Some technical climbing and complicated glaciers.

- AD: Assez Difficile/fairly hard. Steep climbing or long snow/ice slopes above 50º; for experienced alpine climbers only.

- D: Difficile/difficult. Sustained hard rock and/or ice or snow; fairly serious stuff.

- TD: Très Difficile/very difficult. Long, serious, remote, and highly technical.

- ED: Extrèmement Difficile/extremely difficult. The most serious climbs with the most continuous difficulties. Increasing levels of difficulty indicated by ED1, ED2, etc.

Aid climbing grades

Aid climbing is the process of ascending the rock by artificial means. The leader places gear or clips a bolt, then steps up in aid ladders (or etriers) to place the next one. Aid comes into play when free climbing a particular section is too hard — that can happen when the terrain is too difficult to free climb, the weather is so cold it prohibits fine motor skills, etc.

The aid scale corresponds to both technical difficulty and objective danger. Because difficulty depends on the length and injury potential of a fall, harder climbing means gear placements are fewer, farther between, and/or lower quality.

For instance, A1 means a short distance between quality placements that won’t pull out even in a leader fall. A5 means every placement in an entire pitch (area between belay anchors, possibly over 60m) could rip out in the event of a fall.

You might also see the “clean” aid scale: C1, C2, etc. Clean aid simply means there’s no permanent, unremovable, or damaging hardware in the rock, such as bolts. Instead, the leader uses trad gear (see Glossary of Terms above) to aid upward progress, and the follower removes them as (s)he climbs up.

Otherwise, the concepts between aid and clean aid grades are identical.

- A1: Easy aid. No risk of a piece pulling out.

- A2: Good gear with more difficult placements.

- A2+: 10m fall potential from tenuous placements but without danger.

- A3: Hard aid. Many tenuous placements in a row; 15m fall potential; time-consuming.

- A3+: A3 with dangerous fall potential.

- A4: 30m ledge-fall potential with continuously tenuous gear.

- A4+: Greater fall potential and greater technical difficulty, where each pitch could take many hours to lead.

- A5: Extreme aid. A climber can trust nothing on the entire pitch to hold a fall.

- A6: A5 climbing with belay anchors that won’t hold a fall either.

Ratings, applied

In our climbing stories, you’ll never see a rating below 1 on the French Numerical scale (5.0 YDS), because that is just scrambling.

You may see 6b+ (5.10d YDS), which means that the climb is upper-level intermediate, within an experienced, generally fit, and technically literate climber’s abilities.

8a (5.13a YDS) and beyond is considered advanced and 9a (5.14d YDS) is the international standard for elite free climbing. Many Olympic-caliber climbers send 9a or harder, but it is rare air among climbers who don’t get paid to do it.

Conversion chart

Need to work out what an FR rating is in YDS? Here’s a comprehensive grade conversion chart for 10 of the most common grading systems, courtesy of the equipment brand, Bergefreunde.

Note that FR is listed as “French” and the YDS is listed as “USA (Sierra)”.