Four hundred thousand years ago, someone took up a piece of pyrite, struck it against a stone, and started a fire. Archaeologists working on a site in Suffolk have found the pyrite and the scalded clay it left behind. But what species knew how to make fire in Britain almost half a million years ago?

A facial reconstruction of Homo heidelbergensis. Photo: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

About 1.5 million years ago, early hominins — the group ranging from Australopithicus to modern humans, but not apes like chimpanzees or gorillas — maintained fire in open-air sites in Kenya. And 50,000 years ago, Neanderthals may have struck the side of stone bifaces to catch a spark.

The newly discovered evidence in Barnham, Suffolk, fills in a crucial step along the way. It is also now the oldest known evidence for deliberate fire-starting, as opposed to fire maintenance, by an astonishing 350,000 years. Earlier hominins likely used fire arising from lightning strikes or wildfires, but did not know how to create it themselves.

Barnham has long been a fruitful archaeological site. The site attracted at least two separate species of hominin around 400,000 years ago. One of these, which contributed older tools to the site, may have been Homo heidelbergensis. This early human left behind tool remnants in Britain, referred to as the Clactonian culture.

Not dull cavemen, after all

The second culture probably left behind the evidence of fire-starting. They weren’t Homo sapiens, who were still living it up in East Africa at the time. The most likely candidate is Homo neanderthalis. A Neanderthal site from approximately the same era was found at nearby Swanscombe, although no human remains have been discovered at Barnham.

Long stereotyped as dull cavemen, Neanderthals were our closest cousins. Recent research shows they made art and ritually buried their dead. Now, it seems they may have started fire as well.

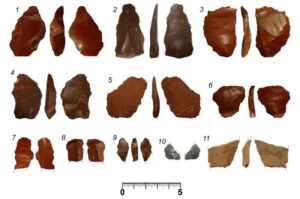

Flecks of pyrite found on flint in the sediment suggest fire-starting. Photo: Davis et al 2025

This second, likely Neanderthal culture at Barnham used fire. It left its scars in reddened clayey silt scattered around the site, rich in haematite. Haematite forms when iron-rich minerals are heated.

The team behind the new research, published in Nature, experimented with burning sediments to recreate the distribution of haematite and the magnetic properties of the silt. The closest replica came from a dozen four-hour exposures to temperatures between 400-600°C, a typical hearth temperature.

But it’s the flecks of pyrite found at the site that may have just rewritten our understanding of human technological evolution. They were found scattered among pieces of stained flint, and they didn’t match any sediment in the immediate vicinity of the site. Someone had brought them there.

Striking pyrite against flint is one of the oldest methods of starting a fire. These pyrite pieces transform the Barnham site into an enigmatic glimpse into the creativity and technological advancement of early human species.

Unless bones are discovered at Barnham, however, we can’t confirm exactly who these brilliant cousins of ours were.