Researchers studying prehistoric rock art on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi have discovered weird-looking and incredibly ancient handprints stenciled on a cave wall. The elongated handprints were created between 75,400 and 67,800 years ago, making them at least 1,000 years older than the previously oldest rock art from Spain.

The handprints are on the wall of a limestone cave called Liang Metanduno on the small island of Muna, just off the southeastern coast of Sulawesi. We’ve known that Sulawesi was home to some of the world’s oldest rock art, with 51.4k and 43.9k-year-old examples already confirmed. Only recently, however, have researchers, led by Adhi Agus Oktaviana of Griffith University in Australia, subjected southeastern Sulawesi to archaeological scrutiny.

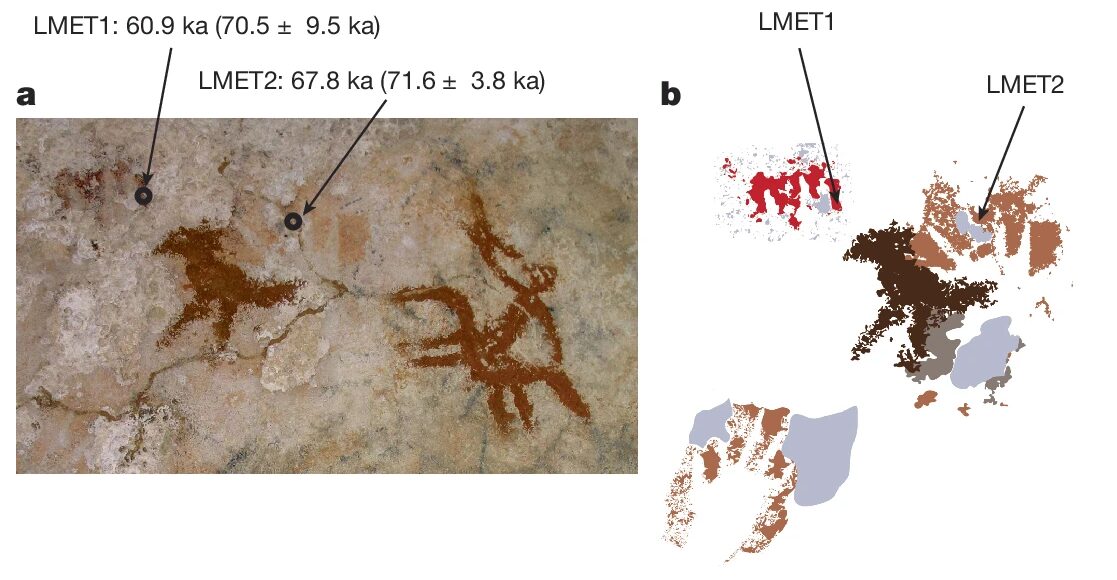

In its new study, the team used LA-U-Series analysis to investigate the rock art. This dating method uses isotope ratios to determine the age of calcium deposits that formed on top of the art, and therefore must postdate it. The results confirm that the Liang Metanduno handprint is at least 1,100 years older than another hand stencil on the Iberian Peninsula.

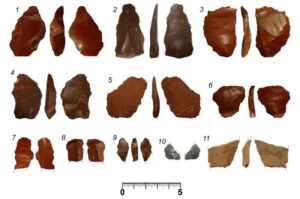

Chemical samples from this faded handprint show it’s around 68,000 years old. Photo: Oktaviana et al

Implications for human migration

This date also marks the earliest confirmation of human presence in Wallacea — a region of eastern Indonesia. Around 70,000 years ago, humans left Eurasia and made a series of sea journeys to arrive in Sahul. Sahul is an ancient continent comprising modern Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea, which low sea levels made a single landmass.

But academics still debate what route early humans took: the southern route from Java to northwest Australia, or a northern route starting from Borneo, touching Sulawesi, and then landing on the western coast of Papua. The presence of human art in Sulawesi dating back to the time of the migration points toward the second, northern route.

The age of the handprints alone changes our understanding of human migration and artistic development. But their unique shape also hints at a complex ancient culture. By either moving their hand during application or adding more pigment manually, the Pleistocene artist made the fingers look narrow, sharp, and claw-like.

This type of claw hand print is unique to Sulawesi. Other examples date from many thousands of years later. Evidence suggests that earlier hominid relatives lived on Sulawesi between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago. But the claw-like alterations to the classic handprint design, the researchers argue, show the artistic sophistication of Homo sapiens.