As the Everest summits begin, climbers must be aware of an extra concern besides the thin air and the effort: their heart condition. Climber and cardiologist Thomas Pilgrim headed a recent study that showed one-third of Everest climbers suffer cardiac arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) during their ascent.

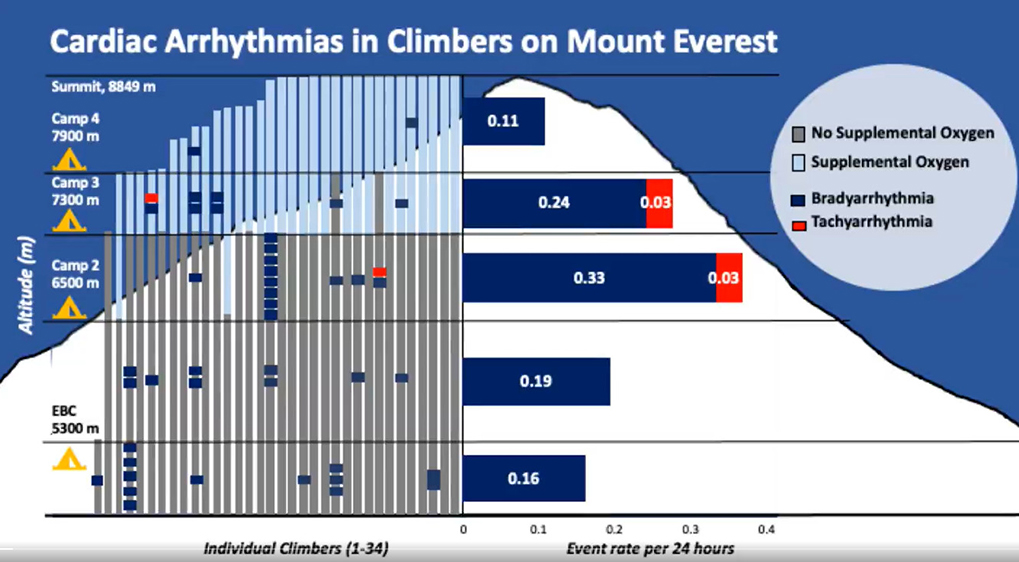

Chart shows arrhythmias among Everest climbers and where they happened. Graphic: SUMMIT project

13 of 41 climbers had arrhythmias

The SUMMIT study took place during the spring of 2023 and involved 41 volunteers, all supposedly healthy. Fourteen of them eventually summited, while the others retreated at some point on the South Col route. There were 45 arrhythmias over 13 individuals. None of these arrhythmias showed obvious symptoms.

Researchers took various cardiac measurements of the 41 climbers and did an exercise stress test before the expedition. They recorded continuous heart rhythm measurements before and during the expedition.

While the proportion of climbers with arrhythmia remained stable as the altitude increased, the number of events per 24 hours increased with altitude between Base Camp and Camp 3 (at 7,000m). The event rate then decreased. Roughly 80% of the arrhythmias occurred in climbers with no supplementary oxygen.

“Many of the volunteers were sherpa climbers, which gave the study an extra benefit,” Pilgrim told ExplorersWeb in a Zoom interview from Switzerland. “After all, they are the people who spend the most time on the mountains and are the most exposed to altitude.”

No clear diagnosis

Pilgrim noted that when people die on Everest from something other than an accident, there is often no clear diagnosis. It can be unclear if such deaths, usually attributed to Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), were preventable. So one of the key aims of the study was to learn whether arrhythmias were partly to blame.

All participants had previous experience at altitude.

“This is probably a selection bias, but people who don’t tolerate the altitude would hardly make it to the summit of Everest and probably have the most arrhythmias,” Pilgrim said. “So what we had in the end was a selection of healthy people [who were] already acclimatized.”

Pilgrim climbed Everest himself and participated in the study. He eventually retreated near the South Col, without summiting. He suffered no arrhythmias during his climb.

Sherpas in Everest’s Khumbu Icefall. Photo: Sagarmathaa Pollution Control Committee

Asked whether the sherpa guides, who are exposed to altitude most of the year, could end up with arrhythmias from the chronic stress, Pilgrim said the study is too small for such a conclusion. However, the current study suggests no such relationship. Some participants had summited 10 8,000m peaks and didn’t fare any worse than others.

“Perhaps there is a genetic predisposition to arrhythmias,” Pilgrim said.

Bearing in mind the limitations of such a small sample, the project did contradict a previous study that suggested sherpas are immune to arrhythmias. “They can have the same cardiac issues as anyone else,” Pilgrim explained.

How to tell arrhythmia from fatigue

Another question is whether the arrhythmias were from the altitude or simply the result of strenuous effort, such as an Ironman triathlete might experience at sea level.

“There are differences,” Pilgrim said. “At high altitudes, you have characteristic breathing patterns. For instance, periodic breathing (apnea) during sleep creates conflict between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve systems and increases the risk of developing bradycardia. Also, in these hypoxic environments, you tend to hyperventilate and that causes electrolyte disturbances, which can lead to tachycardia.”

Another interesting finding is that the arrhythmias stop the moment the climber descends. It’s not permanent damage. Equally, the use of supplemental oxygen radically diminishes the risk of arrhythmias.

Kami Rita Sherpa on his 28th Everest summit last year. Photo: Kami Rita Sherpa

Prevention tips

“Have a thorough cardiac checkup before going to the mountains and consider using supplemental oxygen,” Pilgrim recommends.

It is worth noting that some arrhythmias are more dangerous than others. “The most concerning is the tachyarrhythmias [the heart beats too fast]. Those were the least registered during the study,” Pilgrim said.

He suggests that further studies could explore whether some medications might change the electrical conduction of the heart that controls its beating. “We need to research if and how an unfortunate combination of medication and altitude could lead to a cardiac episode.”

Everest climbers with Furtenbach Adventures have their vital signs monitored from Base Camp. Photo: Furtenbach Adventures

But how can you tell tachycardia from fatigue?

“It is very hard…unless someone is monitoring you,” Pilgrim said. “There are so many dangers up there that most climbers consider cardiac arrhythmias the least of their problems. In the future, technology should permit people to monitor climbers from Base Camp.”

The SUMMIT project is just a first step. Further studies should follow.

Further studies

“It will be interesting to identify individuals who may develop potentially dangerous arrhythmias. And then to find how to minimize the chance of developing them.”

Hopefully, future studies will tackle important safety questions for high-altitude mountaineering. In particular, since modern logistics allow for much larger and faster expeditions, it would be interesting to know if the rushed pace of expeditions increases arrhythmias. Pilgrim agrees that this needs further research. “But I think there might be a correlation,” he ventured.

You can read the SUMMIT study here.

Dr. Thomas Pilgrim and a Nepalese climber during his attempt on Everest last year. Photo: Thomas Pilgrim

Dr. Thomas Pilgrim is a cardiologist and associate professor at Bern University Hospital. While his specialty is valvular heart disease, his collaboration with Nepalese colleagues led to research on high altitude-induced heart disease. “I have a particular interest because I am a climber myself, a Cho Oyu summiter, and I attempted Everest last year,” he says.