The Kihansi spray toad officially became extinct in the wild in 2004. Native to Tanzania’s Udzungwa Mountain, the tiny toads disappeared abruptly within just a few years. Researchers have now identified the cause of their demise.

A fungus — Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) — has been tearing across the globe for decades. It is one of the world’s deadliest wildlife diseases and is responsible for the extinction of 90 species of amphibians and the near-extinction of another 500 species. Most of the victims are tropical frogs. One strain of the fungus does most of the damage.

Vance Vredenburg, co-author of a 2023 study on its emergence in Africa, said that by comparison, this wildlife pandemic makes the Black Death of the Middle Ages “look like a drop in the bucket.”

Bd fungal spores spread in bodies of water, which is why they affect amphibians so readily. The spores float in the water and latch onto unsuspecting animals through direct contact. Once they touch an animal’s skin, the pathogen invades its host’s body, leading to a horrific list of symptoms — skin peeling, ulcers, locked joints, and eventually, cardiac arrest.

Overlooked strain

New evidence suggests that a different strain, formerly considered relatively harmless, caused the Kihansi spray toads to die out. BdCAPE is endemic to Africa, but the main strain is so prevalent across Europe and even Africa that for decades, the risk posed by the less common strain was overlooked.

“It appears that we’ve underestimated the aggressiveness of this particular lineage,” Matthew Fisher, co-author of the new study, told Science.org. “As it’s all over Africa, this is a real problem.”

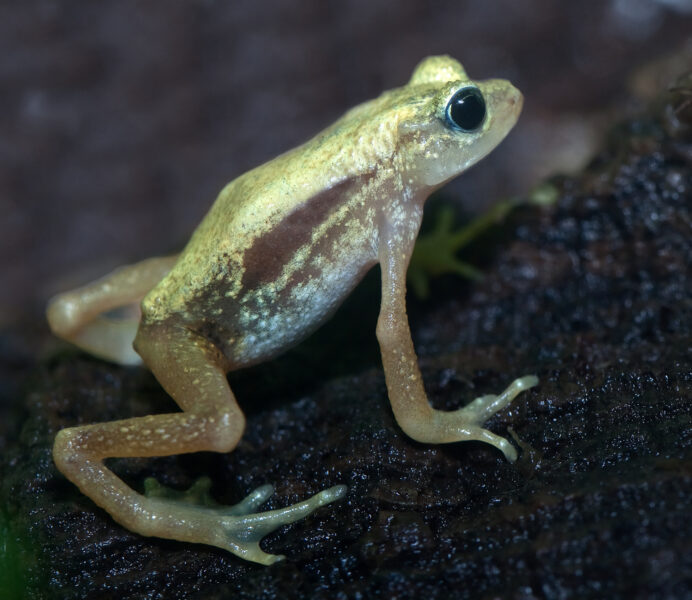

Kihansi spray toad. Photo: Shutterstock

The Kihansi spray toad is a bright yellow and only a few centimeters long. It lived in just one habitat — the wetlands beside the waterfalls of the Kihansi River, an area of just 0.01 square kilometer. The population was seemingly healthy, then in 2004, it disappeared forever.

The frog’s decline started with the construction of a dam on the river. The wetlands began to dry out, and the little toads could not cope. A sprinkler system was set up to try and save them. Though successful for a while, the toads still died out. Everyone believed it was another consequence of the deadly Bd fungus, combined with the stress from the new dam.

Waiting for science to catch up

It turns out that it was actually due to the spread of BdCAPE. Epidemiologist Che Weldon collected some dead frogs in 2004 and preserved them in his lab for two decades, waiting for technology to catch up and allow the dead frogs to be studied.

Two decades later, a team sequenced the DNA of the fungus that infected the long-dead toads. The strain was definitely BdCAPE. The analysis also showed that the toads started dying out just before the strain hit their little area.

Over the years, a lot of research has taken place at this biodiversity hot spot in Tanzania. Other studies from 2004 showed that many other amphibians were also infected with BdCAPE, though their symptoms were far milder than those afflicting the Kihansi spray toad.

Twigged to the potential danger of this overlooked strain, the team did an experiment to show that BdCAPE is far more dangerous than anyone suspected. They infected amphibians with both strains to see exactly how BdCAPE compared to the more prevalent global strain. In many amphibians, BdCAPE was far more aggressive.

“BdCAPE is not the well-behaved child that we thought it was, at least not in Africa,” commented Weldon.