A pirate capture, a daring escape, a deserted island — it all seems like material from an old swashbuckling movie, probably with Errol Flynn. But in 1722, a young fisherman named Philip Ashton found himself in just such a narrative.

He was thrown into captivity in a pirate ship, which brought him halfway around the world before he managed to escape — getting away only to spend 16 months as a castaway on a small Caribbean island. His desperate fight for freedom and survival is not well known today, although it became the subject of a famous writer’s adventure novel.

Captured by pirates

Born Aug. 12, 1702, Philip Ashton was only 19 years old in the summer of 1722. But as a Cape Cod man from Marblehead, Massachusetts, he had been at sea all his life. He was captaining the Milton, a small schooner. His crew included childhood friend Joseph Libbey.

On their way to the fishing grounds off Cape Sable, the Milton anchored in Port Roseway with a dozen other small fishing vessels. At first, none spared a second thought to the larger brigantine — a two-masted sailing ship — anchored alongside them.

When a boat with four men launched from the brigantine, it didn’t worry Philip and his friends. They thought the vessel was a merchant, coming to trade news. It wasn’t until the four men were aboard the Milton, drawing cutlasses and pistols, that their nature was revealed. Caught completely unawares, the Milton crew surrendered. The pirates took another dozen small fishing vessels the same way.

When Philip and the other captives were brought aboard the brigantine, they received a second shock: They hadn’t been taken by just any pirate. Their lives were now in the hands of the infamous Ned Low.

The brigantine which took Philip was called the ‘Rebecca.’ These ships were swift and easy to handle, making them a favorite with pirates. Photo: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Captain Ned Low

Edward Low was born in Westminster and went to sea as a child. As a young man, he settled in Boston and worked producing rigging for sailing ships. He married and had a child, but after the sudden death of his wife, a devastated Low fled to the sea.

He initially joined the British merchant marine, but in 1721 he led a mutiny. Taking over the ship and shooting the captain, he and the crew turned pirate. By Philip’s capture, Low’s ship had almost 50 men and six powerful cannons.

Low also acquired a reputation for brutality. Contemporary sources reported that he regularly mutilated and tortured his captives. At this time, pirate crews signed “articles,” basically a contract of employment, outlining the shipboard roles and rules.

Some other captains, such as John Philips and Thomas Anstis, had clearly outlined punishments for crimes such as mistreatment of prisoners, rape, or striking a fellow sailor. Low’s articles are unconcerned with these crimes, but do specify that the punishment for desertion was death.

One particularly brutal incident took place after the capture of the Portuguese ship, Nostra Signora de Victoria. Unable to find the expected treasure, Low tortured several prisoners. They admitted that during the preceding chase, the captain had thrown £15,000 worth of gold over the side. Incensed, Low cut off the captain’s lips, boiled them, and forced him to eat them. Then he had every captive killed.

Though these accounts were published during Low’s life, they were highly sensationalized. Modern scholars don’t think Low was necessarily any more brutal than his contemporaries. Low also had his code of honor, as Philip was about to discover.

In one account of Low, he threatened to shoot a captive if he didn’t drink punch with him. Photo: Woodcut from ‘The Pirates Own Book,’ F. Blake, 1855

Pressed and oppressed

For much of maritime history, a significant number of every ship’s crew were “pressed” men. These were merchant sailors, fishermen, and others who were captured from shore or abducted from other ships and forced to work as paid slaves. Pirates did this, but so did the British Royal Navy, and other European and American navies.

As they hauled him aboard, Philip was determined not to join the pirates. The pirates selected a half-dozen young men who looked healthy and strong. In addition to Philip Ashton, the select included his friends Nicholas Merritt and Joseph Libbey.

Pistol in hand, Low faced them on deck and asked a surprising question: Were any of them married? Surprised, and frightened by the gun he was brandishing, they said no, they were not. This, Philip later learned, was a firm rule Low held. Haunted by his own loss and the child he left in Boston, he wouldn’t take away a married man.

Unfortunately, none of them were husbands. Low demanded that they sign his articles, and they refused. Then he threatened. Then he promised riches and drink. Philip and his friend Nicholas Merritt remained firm. Irritated, Low added them all to the books anyway, and the fleet set sail, carrying Philip away from family and freedom.

Pirate crews were largely recruited from captured vessels. How voluntary this recruitment was is hard to say. Photo: Private Collection; Peter Newark Historical Pictures

Life with the pirates

Philip did not have the temperament for piracy, and his unwillingness to cooperate only worsened things. The rough, noisy, and drunken men shocked his moral sensibilities, so he spent much of his time hiding in the hold.

Per Low’s articles, they couldn’t kill a man once they had given him quarter. But Philip didn’t learn that for some time, and was constantly terrified that he’d be executed. When the pirates remembered he existed, or got bored, they’d rustle him out of his latest hidey-hole and demand he join them, beating him when he refused. His particular tormentor was the quartermaster, John Russell, a notorious pirate in his own right who chased Philip about the ship with a cutlass on multiple occasions.

Off the coast of Maryland, Low’s crew captured the Portuguese ship Rose-Frigate. Taking a liking to the larger, better-armed vessel, Low renamed her the Rose Pink. He moved the bulk of his crew, including Philip, into the Pink, which sported a very respectable 14 guns.

They captured a sloop off the Cape Verde islands, and Philip’s friend Nicholas Merritt was one of the eight men chosen to crew her. However, they were mostly pressed men, so the crew slipped away from the rest of Low’s fleet.

While Merritt quietly escaped, Low went to the West Indies, where he promptly sunk the Rose Pink due to mishandling during routine repairs. Philip was cast into the water, and two boats of pirates passed by him without allowing him aboard. He was finally saved by his friend Joseph Libbey, who had integrated into the pirate crew but remained close to Philip. Another close escape.

A woodcut of Ned Low during a terrible storm, which Philip experienced. Photo: National Maritime Archives

Out of the frying pan…

Loading everyone into the surviving sloop, Low, under false colors (deceptively flying an incorrect flag) sidled casually into the French-controlled harbor of Grand Grenada. He claimed to be an innocent merchant vessel in distress. The concerned French loaded up a ship and came up beside him, trying to determine if he was a smuggler. When Low gave the signal, 90 pirates burst out. They took over both ships, sailing them off.

Low captured more ships and took to calling himself Commodore. With every move, they dragged Philip along. The more Philip pleaded to go home and refused to join, the more Low swore that Philip would only go home when he did, and not before.

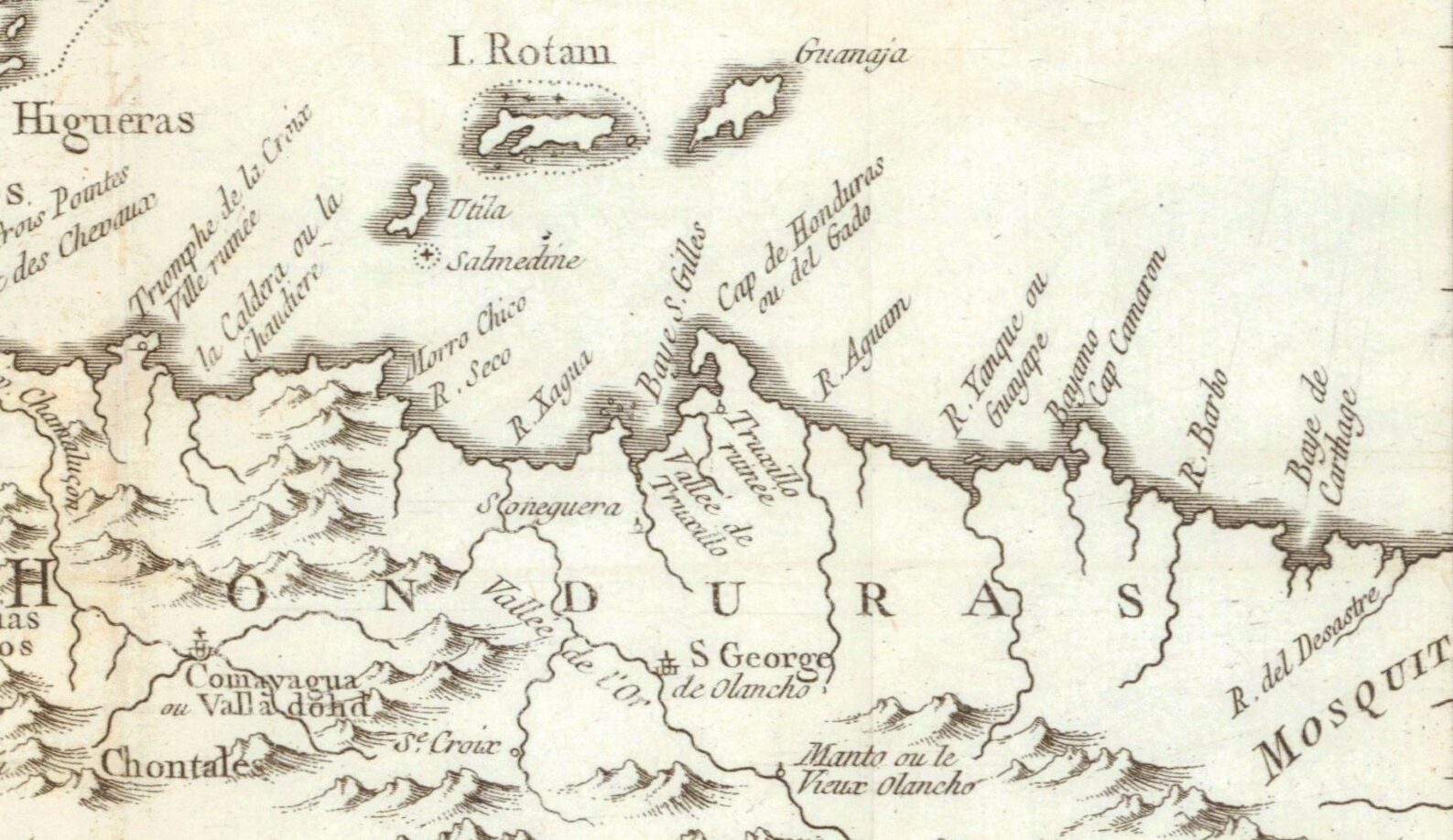

But more ships meant more maintenance, and soon Low had to anchor in the Gulf of Honduras, between Honduras and Belize. Low and his friends settled onto the island of Port Royal Key to drink and carouse. Low sent the rest of the crew to the nearby island of Roatán to clean and resupply the ships.

There, Philip saw his chance. The ship’s cooper was preparing to go ashore and refill the water casks. He needed several men to help him, and Philip begged to be one of them. Thinking he wouldn’t attempt to flee onto so deserted and remote an island, the cooper agreed.

Once on shore, Philip said he was going to go gather coconuts. Instead, he fled into the jungle. His practice of hiding in the hold came in handy. Philip burrowed into a dense thicket and lay still and silent. After some yelling, the cooper realized Philip wasn’t coming back. Deciding that searching would be a waste of everyone’s time, he left.

This 18th-century map of the Gulf of Honduras shows the lay of the land. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

…Into the fire

Philip was free of the pirates. He was also alone with no food or supplies, on a remote and uninhabited island. He had already been away from home for nine months. Without even shoes, let alone hunting and fishing gear, he had limited options. But Philip determined to make the best of it and began exploring his new home.

Roatán island is a long, thin landmass, 64 kilometers long but only eight kilometers across at its widest. For hundreds of years, it was home to the Indigenous Pech people. In 1502, Christopher Columbus landed on the island, enslaving many of its inhabitants and forcing others into mining camps on the mainland. By the time Philip arrived, it was uninhabited. However, on the beach, he found broken pottery, which showed the Pech had once lived there.

The Spanish, too, had abandoned Roatán, leaving the battered remains of old fortifications. Along with Philip, the island was home to a diverse array of animal life—wild hogs, deer, seabirds, and tortoises. But without any tools to trap or butcher them, Philip could only eat the fruit that grew on the island.

He made a small hut out of palmetto leaves, but mosquitoes, venomous snakes, and stinging gnats continually harassed him. As the days passed, Philip grew weak and hopeless. He spent more and more time slumped on the beach, looking out at the water, wishing for a rescue that didn’t come.

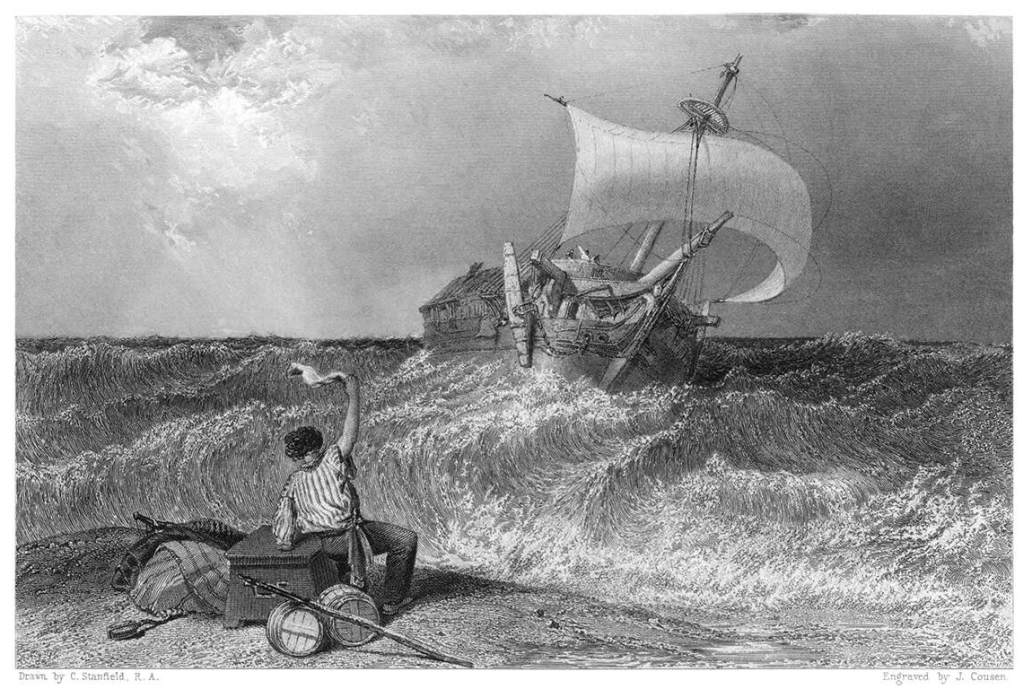

Though he tried to occupy himself with swimming and exploring, Philip longed to sight a ship. Photo: Old Book Illustrations Archive

The fate of Joseph Libbey

A pirate’s career rarely lasted more than a few years. In June of 1723, a British Navy warship caught up with Low. The HMS Greyhound, captained by Peter Solgard, had twenty guns and 120 men. On the other side, the pirates had two smaller ships, the 10-gun schooner Fancy, captained by Low, and the small sloop Ranger, under his protege, Charles Harris.

Captain Solgard used Low’s own tactics against him, pretending to be a helpless whaler. Low, lured in by the thought of all that expensive whale oil, gave chase. When he came alongside, the Greyhound ran the Union Jack up the mast and opened fire.

Both Harris and Low decided to cut their losses and flee, but only Low, in a battered and demasted Fancy, managed to escape. Solgard took the Ranger and its crew into custody. Captain Solgard won fame and fortune from this victory, eventually rising to the rank of admiral.

Twenty-five captured men were sent to trial in Newport, Rhode Island. Among them was 21-year-old Joseph Libbey. Libbey may have been pressed into service, but he could still be prosecuted for his involvement.

Doctor Kencate, the Ranger‘s surgeon, testified against Libbey, claiming he’d been an “active man” on the crew. Libbey had, Kencate alleged, boarded and plundered ships and had fired his weapon during these raids. Another former crewmate had seen Libbey loot a pair of silk stockings from a vessel the pirates had taken.

Libbey protested that he was a pressed man, but to no avail. On July 19, he and 24 other men were hanged from the gallows on Gravelly Point. They were buried in a mass grave on the beach of Goat Island, in the unhallowed ground between the low and high-tide marks.

A pirate being hanged. Photo: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

The English stranger

While Libbey was on trial, Philip Ashton was growing sick and weak in the jungle. He was always tired, and his whole body was sore and bruised. A number of nutritional deficiencies can come with a fruit and occasional scavenged egg diet. Lack of iron, calcium, and B vitamins likely made Philip weak, as did a lack of protein.

Still barefoot, his feet were covered in wounds, which made it painful and difficult to walk. After nine months on Roatán, Philip believed he was near death. Worse, the rainy season had begun, drenching and chilling him to the bone. Between storms, he baked in the tropical sun.

Then one day in November, Philip saw a canoe on the water. In it was a man, very startled to see a haggard Philip slumped on the beach. The stranger was a grave Englishman who had been living in Spanish Honduran settlements for two decades. But, having committed a crime he never specified, he had fled with his dog to Roatán Island, to wait for the heat to die down.

He was kind to Philip and took on the responsibility of hunting for them both. He said very little about himself, not even his name. Three days after arriving, he left again, saying he was going to hunt on another island. A storm blew in, and he never returned. Lost at sea or gone back to the Spaniards, Philip didn’t know. But he was once again alone.

Still, things were looking up. The stranger had left behind the two tools Philip most needed: a flint to light fires, and a knife.

While beautiful, the island was a slow death for Philip without any survival tools. Photo: Shutterstock

Castle Comfort

Better equipped, Philip’s quality of life rapidly improved. He returned to exploring the island and found an old abandoned canoe. To his relief, it was not the canoe of the stranger, who was likely still alive somewhere. Now the lofty possessor of such wonders as a knife and old canoe, a cockier Philip began to call himself, as he later recounted, Admiral of the Neighboring Seas.

He got an unpleasant shock when the crew of a Spanish sloop had stopped by. Caught napping, Philip woke up to people shooting at him, which experts agree is one of the worst ways to wake up. He fled into the jungle, and they left.

In June of 1724, Roatán once again had visitors. A series of rowboats appeared on the horizon, bearing what Philip initially feared were pirates. Actually, they were 18 local baymen, English woodcutters, who had fled from Spaniards on the mainland. They also brought one Indigenous woman as a servant.

They settled in, giving Philip better clothes and building a house they called Castle Comfort. But Philip was wary — the baymen were suspicious characters, half pirates themselves.

After four months of cohabitation, who should return to the island but, astoundingly, Captain Low’s pirates. Philip and three men were away hunting on the nearby island of Bonacca when Captain Spriggs, Low’s old lieutenant, landed in Roatán and attacked Castle Comfort. Philip and the three men with him fled in the canoe, and Philip once again hid in the dense jungle to avoid capture. The baymen who survived the attack took an old sloop the pirates had left behind and departed the islands.

The flag used intermittently by Low, Spriggs, and another piratical collaborator. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Two years, ten months, and fifteen days

Philip and a man named John Symonds, as well as a black man enslaved by Symonds, elected to stay on the islands. Another few months passed. Finally, the season was approaching where Jamaican traders would stop by Bonacca to take on water, so the trio moved there to wait.

Only a week later, an entire fleet of English ships came over the horizon. It was a merchant convoy and its escort Diamond, a British Man-of-War. A brigantine approached the shore, and Philip, calling out that he was a friend, drew its attention. Onboard, his years of wretched luck continued to reverse. The commander of the brigantine was Captain Dove, an old Massachusetts acquaintance of Philip’s.

Dove signed Philip onto his crew. It had been two years, 10 months, and 15 days since his capture, and he was finally heading home. On May 1, 1725, Philip Ashton returned to New England. The same night, he made it to his father’s Marblehead house.

Philip returned to the sea, making a living as a fisherman, but managed to avoid further adventure. He married, was widowed, remarried, and had seven children. He was laid to rest in Old Burial Hill in his beloved Marblehead.

Philip’s final resting place on Old Burial Hill, in Marblehead. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Philip Ashton’s literary afterlife

Philip’s story of perseverance and deliverance appealed to his pastor, a man named John Barnard. It was Barnard, through consultation with Philip, who wrote Ashton’s Memorial, an account of Philip’s adventures. Though intended as a demonstration of God’s power to save, it became popular as an adventure story.

One of the readers was English writer Daniel Defoe. Today, he is most famous for Robinson Crusoe, but he authored many fictional and nonfictional accounts of piracy, shipwreck, and maritime adventure. His last novel, published in 1726, was The Four Years Voyages of Capt. George Roberts. It follows a man who is captured by Ned Low, then escapes and becomes a castaway. Many of the details are taken directly from Ashton’s Memorial.

This adventure novel, based on Philip’s story, is not one of Defoe’s most famous works. But perhaps this suited Philip Ashton just fine. Despite his colorful escapades, he was at heart a humble fisherman who wanted no part in nautical adventures.