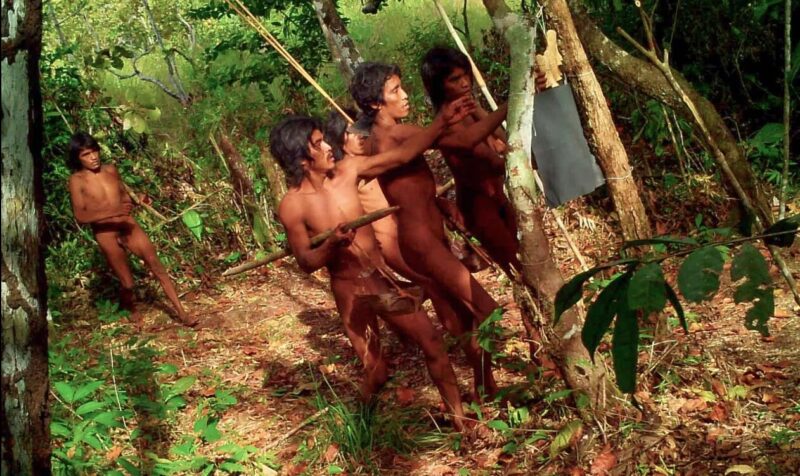

Automatic cameras in the Amazon have captured images of an uncontacted Indigenous community.

Dubbed the Massaco people after a nearby river, they live in the Brazilian rainforest near the border with Bolivia. No one knows what they call themselves.

Photo: Funai

According to Brazil’s National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai), the Massaco population has doubled to over 250 people since the 1990s despite constant pressure from encroaching civilization. The Funai have been working to protect 28 known isolated Indigenous communities since 1987, and their methods seem to work.

No-contact policy

That year, Brazil established a no-contact policy to keep outsiders from intruding on the isolated communities. Several other South American countries have also adopted the policy to minimize the spread of contagious diseases. Before this, 90% of those who were contacted, usually through government-led programs, died from disease. Because of their isolation, they have no acquired immunity from the infections and diseases common in the rest of the world.

The Massaco people hunt with bow and three-meter-long arrows. Photo: Funai

The Funai have also increased efforts to protect the areas around such communities and minimize deforestation. The growth seen in the Massaco community mirrors that of other protected groups.

Despite the photos, we know almost nothing about the Massaco. Their language, social structures, and beliefs are a complete mystery. Altair Algayer has spent over 30 years working to protect this community. After analyzing the photos, he told The Guardian, “With the detailed photographs, it’s possible to see the resemblance to the Sirionó people, who live on the opposite bank of the Guaporé River in Bolivia. But still, we can’t say who they are. There’s a lot that’s still a mystery.”

Photo: Funai

Why the cameras?

Algayer placed the cameras in the rainforest. All the images come from 2019 to the present day. He set them up near where the Funai leaves tools for the uncontacted group to try to stop them from venturing into nearby farms or logging compounds.

The team also uses satellite imagery to keep track of the Massaco.

“[Recently], we’ve seen more new tapiris [thatched huts], so I wouldn’t be surprised if there are 300 individuals,” Algayer said.

To some, capturing these images may seem to go against the no-contact policy. But it is important to document that the group continues to exist. Otherwise, their protections may be lost.