It’s a bad month for any malicious asteroids out there. On Sept. 4, an observer at the Catalina Sky Survey spotted an asteroid bound for the Philippines eight hours before it disintegrated in the sky. Eight hours’ notice would be enough to evacuate inhabitants in the case of a city-killer asteroid. People: one, asteroids: nil.

Then, on September 23, experimental physicists at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico showed that X-rays resulting from a nuclear blast could be enough to send even a planet-killing asteroid running in the other direction. To do so, they invented a new experimental technique. Now, scientists can test this kind of deflection without ever having to go to space.

The Science and Technology Park at Sandia National Laboratories in the foothills of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photo: Texas Tribune

The threat of large asteroids

There are currently no asteroids on a collision orbit that are big enough to alter the global climate, much less wipe out humanity. Still, it’s always possible that an interstellar visitor such as ‘Oumuamua could pick our tiny blue dot as its new home, much to our detriment.

An artist’s rendition of the interstellar object ‘Oumuamua. Photo: ESO/Martin Kornmesser

We know from the Double Asteroid Redirection Test that a rocket can deflect an asteroid from its path by hitting it at high velocity. But for some time, scientists have predicted that only a nuclear blast would be sufficient to deflect a kilometer-sized asteroid. Computer simulations agree that it will work. Figuring out how to test it in a lab has been a lot harder.

Nuclear blast deflection

Discussions of nuclear blast deflection tend to center on the shock wave from the explosion changing the orbit of an asteroid. Nathan Moore and his team at Sandia National Laboratories focused on a different tool in the nuclear explosion arsenal.

Nuclear blasts release large quantities of X-rays. These energetic photons dissociate (the process of breaking up a compound into simpler constituents) the surface of the asteroid itself, leaving behind a gas that expands in every direction, including toward the rest of the asteroid. The initial shock wave is comprised of lighter gases, but this slower explosion would be made up of heavy, metallic particles. If the initial shock wave is a swarm of flies hitting a car windshield at high speed, the secondary X-ray explosion is a wall of geese. They might move slower, but they’re going to do a lot more.

But testing this concept in space is prohibitively expensive. Worse, if we wait until a hazardous asteroid is already heading toward us, we run the risk of fracturing it into still-dangerous pieces without deflecting it. That means we need to imitate outer space conditions in labs on Earth. But how can we create a target that’s free to move without friction?

X-ray scissors and a machine called Z

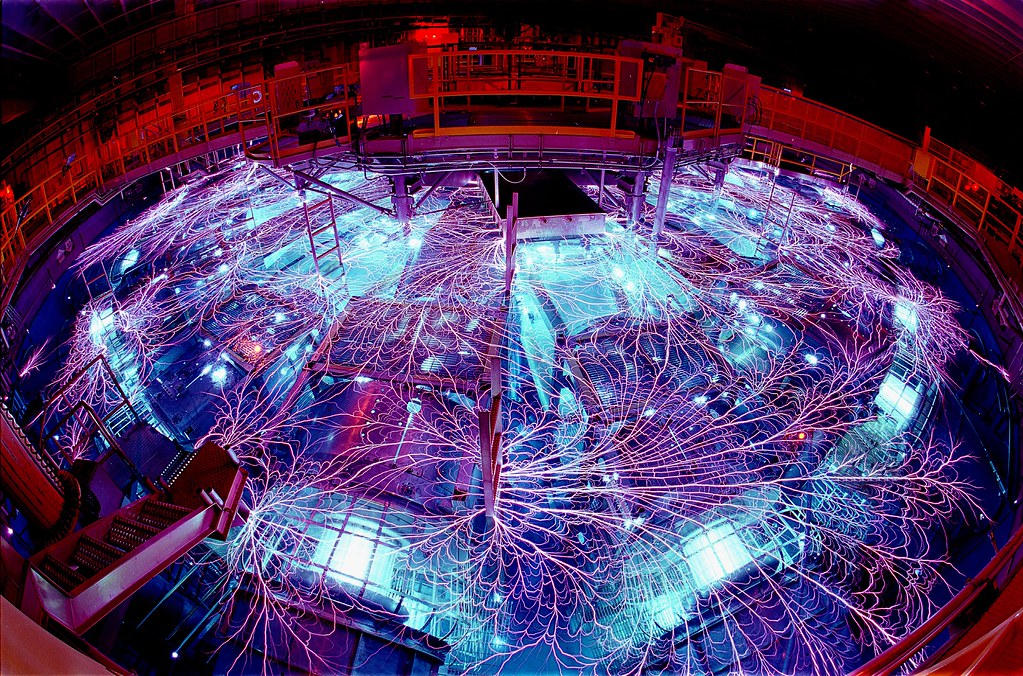

Nestled in the foothills of Albuquerque, New Mexico sits a machine called Z. It is the most powerful electromagnetic pulse generator in the world. By firing it at argon gas, the Sandia team created a plasma in less than a millionth of a second, which released a bubble of X-rays at their asteroid sample.

When it came to mimicking the conditions of outer space, the team had to get creative. The tool they call “X-ray scissors” in their paper may conjure images of mind-bending microscopic technologies such as quantum optical scissors, but these scissors are refreshingly simple. Two pieces of minuscule metallic foil sit at the heart of the new experiment. From them, the team suspended their fake asteroid samples made of silica and quartz. When the X-rays hit the asteroid sample, they dissociate the foil as well. For just a shred of a second, the sample hangs suspended in space, unaffected by the drag of anything around it, pummeled by X-rays.

The team found that in that short time, the asteroid samples accelerated to about 70 meters per second. Through calculations, they showed that a stronger X-ray blast from a real nuclear explosion could deflect asteroids multiple kilometers across, the kind that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Best of all, the team’s X-ray scissors will allow ground-based testing on all kinds of asteroid materials. If an asteroid suddenly heads our way, we’ll have the technology and the practice to deflect it without shattering it.