When the Heinrich-Chrobak went up in 1964, it stood as a milestone: one of the most demanding climbs in Europe, and a feather in the cap of Polish climbers. Nestled in Poland’s Tatra Mountains, on the 500m face known as the Kazalnica Mięguszowiecka, the route was stout in summer conditions — but prohibitive in winter.

So it’s no wonder it took nearly 60 years for anyone to free climb it in winter. That’s what Damian Granowski and Tomasz Klimczak did on March 22-23, rating the Heinrich-Chrobak at a stout M8.

The two Poles wasted no time admitting that spring technically began a couple of days before they started climbing. But winter conditions prevailed on the route at temperatures just above freezing, forcing lots of dry tooling.

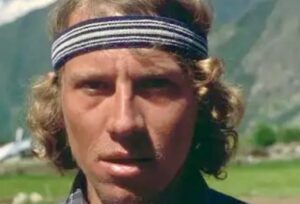

Granowski making his way into the ‘Y’ pitch (M8). Photo: Tomasz Klimczak

“We have such a climate that for several years now we do not look at the calendar, but at the conditions,” Granowski explained in a blog post. “We climbed mainly with crampons and [axes]. Some pitches or their fragments were more lukewarm and hands helped here. It was just right for such drajtulowców like us,” he concluded, using the Polish word for “dry toolers” and posting the smile emoji.

From his and Klimczak’s thorough description, the climbing is consistently serious. Eleven pitches shake down to: M7, M7+, M8, M5, M6+, M7-, M8, M6+, M8, M6, M5.

Approaching the Kazalnica Mięguszowiecka. Photo: Damian Granowski

Granowski cited two previous attempts to climb the Heinrich-Chrobak in “classic” (Polish equivalent of “free”) style, in winter. One was his and Klimczak’s previous effort in 2018. In the other, which a Czech team carried out in December 2020, rockfall near one of the M8 cruxes injured one of the climbers and forced a retreat.

Polish climbers hold a proud, strict tradition. Granowski explained in his post that climbing activity in the Tatras was fervent after World War II, when climbers in the country faced limited venue options.

Progress advanced accordingly. The Heinrich-Chrobak took the first ascent team 32 hours to complete. Nine years later, a team finished it in eight hours, and the speed record was set in 1982 at 3.5 hours. By then, the free climbing wave that swept through Europe had impacted the scene and produced harder and harder climbs.

Dry tooling became popular.

“Gradually, routes were ticked off and the numbers M7, M8, M9 or M10 were raised,” Granowski wrote. “The higher the number, the more dry tooling skills were needed. Plus, of course, a supply of stamina, strength, and psyche. It is strange that Heinrich-Chrobak survived among so many checks.”

Thanks to him and Klimczak, that “survival” period has come to an end.