An Egyptian magician-prince who delves into the crumbling sepulchers of his ancestors in search of forgotten lore: It sounds like the pitch for an early 20th-century pulp adventure novel. But Prince Khaemwaset, living in the 12th century BCE, really was an archaeologist, adventurer, and explorer of his own already ancient civilization.

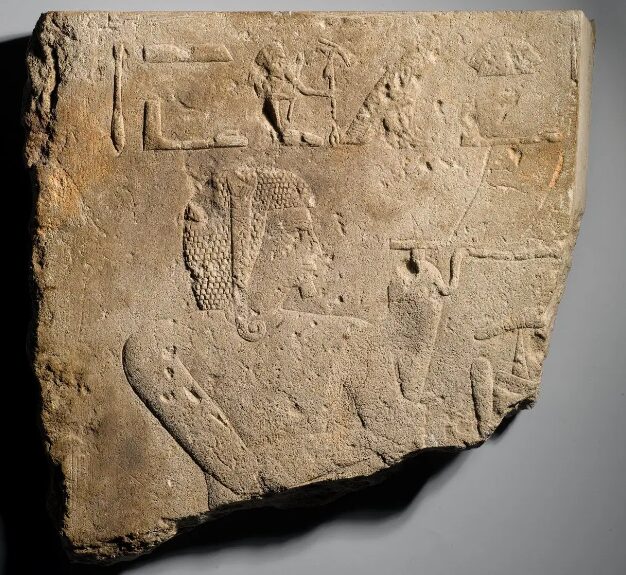

A limestone relief of Prince Khaemwaset, son of Pharaoh Ramesses II. Photo: Brooklyn Museum

The Egypt of Prince Khaemwaset

People were farming and forming permanent settlements in Egypt as early as the 6th millennium BCE. By around 2900 BCE, Egypt was ruled by Pharaohs who built elaborate monuments, used hieroglyphic writing on papyrus, and worshipped gods like Horus. All this to say, when Prince Khaemwaset (also spelled Khaemweset, Khamwese, Khaemwes, and so forth) was born around 1281 BCE, his homeland already boasted a rich history.

He was the son of one of Egypt’s most famous kings, Ramesses II, he whose vast and trunkless legs of stone stand in the desert. Though his mother was only the king’s second wife, Isetnefret, his father didn’t hold it against him. At least in official depictions, Khaemwaset is right next to Amun-her-khepeshef, the son of Ramesses’ beloved first wife, Nefertari.

The two princes were born in the reign of their grandfather and reared in the turbulent days of Ramesses’ early reign. Khaemwaset must have been a good student at school, because he soon entered the priesthood. His order was dedicated to the worship of Ptah, the Egyptian creator-god associated with sculptors and craftsmen. It was his experience there that led him to the efforts he’s remembered for today.

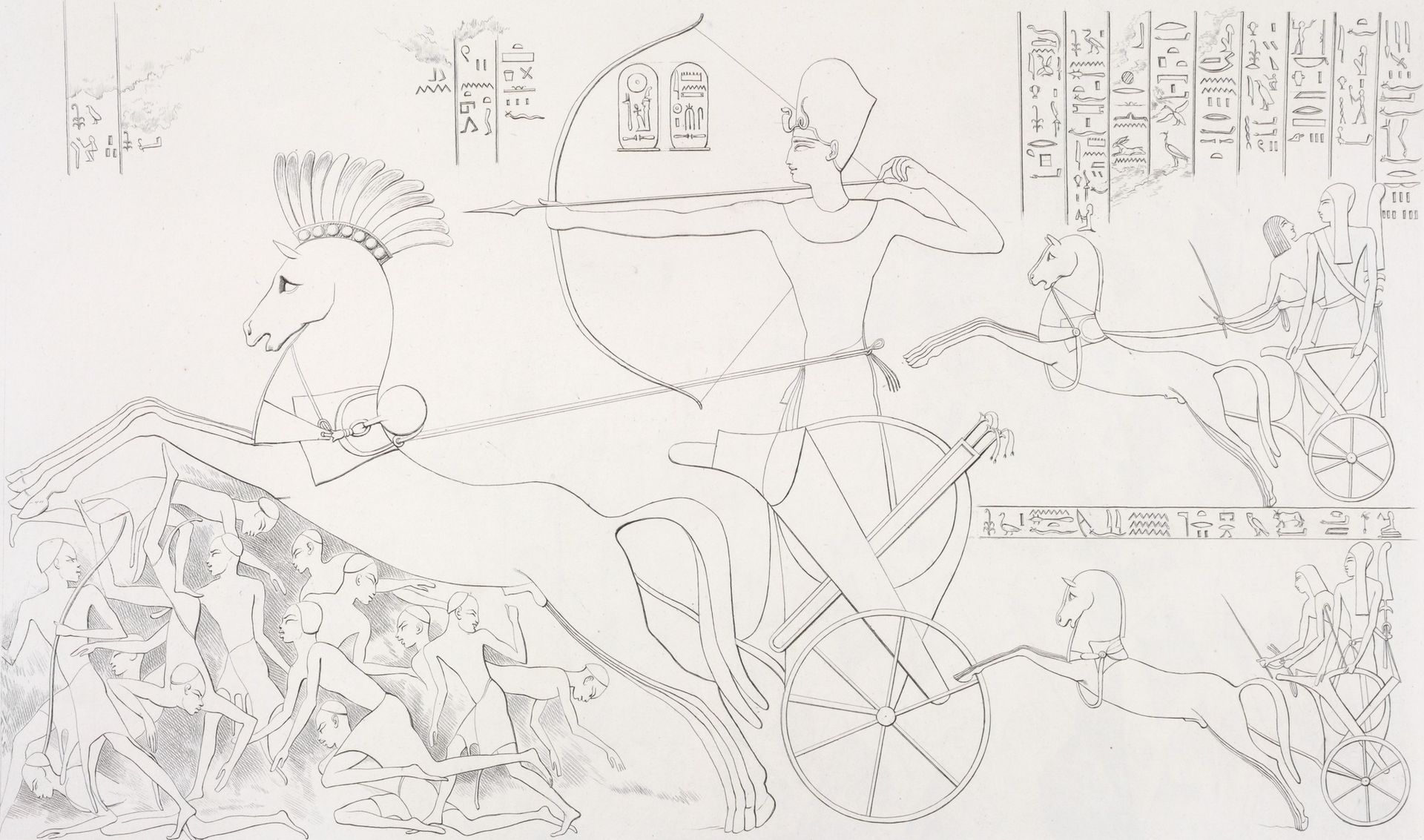

This scene from a war with the neighboring Nubians shows Ramesses II (the larger figure) and his two elder sons (the smaller figures) Prince Amen-hir-wenemef and Prince Khaemwaset. Egyptian art used relative size to express importance, so Ramesses II probably wasn’t six meters tall. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

High priest and archaeologist

The priesthood has been the dumping ground for extraneous heirs across time and place. Prince Khaemwaset, however, seems to have been genuinely passionate and well-suited for a career with Ptah. Ptah, incidentally, became part of the modern word, “Egypt”; from Hikuptah (House of the spirit of Ptah) to the Greek Aigyptos, thence into English as “Egypt.”

More relevantly here, Ptah’s priests were the keepers of royal tradition and of one of the greatest temple libraries in Egypt. Skill, dedication, and, let’s be honest, nepotism, accelerated Khaemwaset’s career. By the time he was thirty, he was the High Priest of Ptah, gaining the title Setem. The title came with great responsibility, as well as a presumably very cool-looking panther-skin robe.

According to inscriptions he had written, the prince was “never happier than when he was reading the records of earlier times.” It upset him that so many ancient monuments were falling into ruin. By the New Kingdom, some of Egypt’s most famous wonders, including the pyramids and the Sphinx, were neglected and crumbling.

His new position as High Priest gave Khaemwaset the power to pursue his passion. He launched an extensive campaign, finding, restoring, and labeling the monuments and artworks of past dynasties. Like modern museum labels, the inscriptions he added to ancient statues explained who had built them, and when (and by whom) they’d been restored.

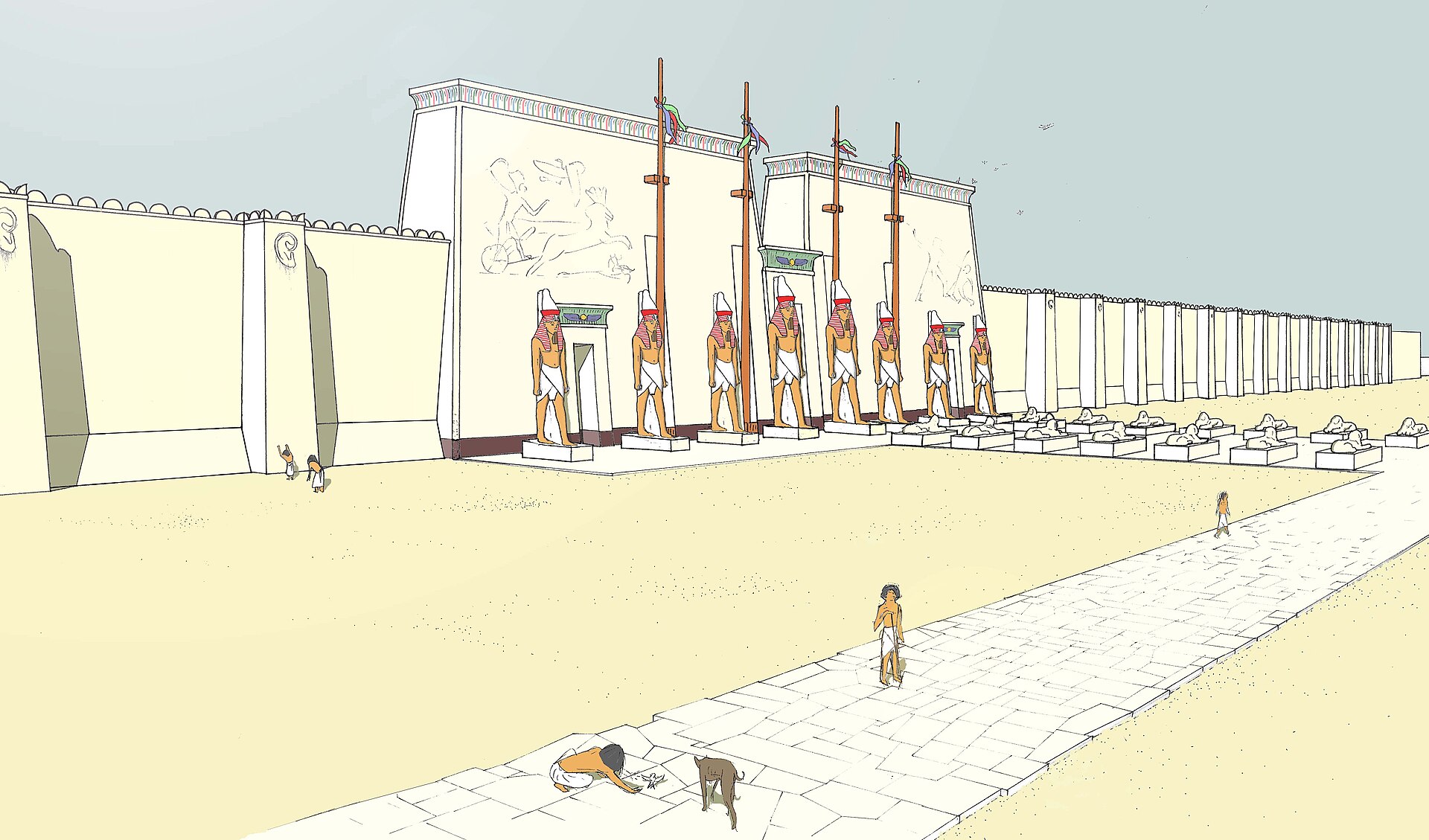

A reconstruction of the great temple of Ptah in Memphis, at the time of Khaemwaset. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Khaemwaset at Giza

Though his priestly duties were extensive, and deaths in the family eventually made him the heir apparent, Khaemwaset only accelerated his restoration work. His greatest efforts came after a visit to Giza and the Old Kingdom necropolis of Saqqara. The monuments there were well over a thousand years old and were half-forgotten and in disrepair.

Using historical documents, he painstakingly matched the ruins with archival records. Then he wielded his position for funds to restore them, and added his inscription labels. He worked on the mastaba of Shepseskaf, the sun temple of Niuserre, the pyramid of Unas, and many others.

His most famous site is undoubtedly the Great Pyramid of Khufu — the largest of the Giza pyramids. Khaemwaset not only restored but also conducted excavations around the pyramid. During these excavations, he uncovered a statue of Kawab, the son of Khufu. He seemed to have been particularly delighted by this statue, which he restored and placed in a special “museum” chapel at Memphis.

The inscription he added says where and how he found the statue, and that he restored it “because he loved the noble ones who dwelt in antiquity before him, and the excellence of everything they made.”

You know it, you love it, aliens didn’t build it: The Great Pyramid of Giza/Khufu/Cheops. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Egyptian pr?

Some academics have pointed out, quite rightly, that the restoration of ancient monuments was a political act which advertised the power and prestige of Khaemwaset’s dynasty, glorifying him and his father. They sometimes cite this in opposition to his popular reputation as a scholar and the first Egyptologist.

I personally find this a strange argument. It’s like saying Captain Scott wasn’t a real explorer because he was motivated by a desire to glorify himself and the British Empire. But yes, I suppose if we’re quibbling, Khaemwaset didn’t do all the monument restoration and research purely for the love of the game.

Whatever his motivation, his archaeological fervor kept his memory alive long after his death. Khaemwaset never became pharaoh. He died in his fifties. Ramesses II died much later and was instead succeeded by another of his many, many sons. But today and in ancient times, Khaemwaset is far better remembered than his younger brother, the pharaoh Merneptah.

Even during his lifetime, Khaemwaset had a reputation for possessing mystical, ancient knowledge. Khaemwaset’s compositions used cryptography and obscure, archaic styles, and his willingness to enter ancient tombs garnered both admiration and fear. After his death, this reputation evolved into a mythology which became a literary genre.

The Setne (from his title, Setem) stories from Ptolemaic-era Egypt are adventure tales, about the exploits of the magician-Prince Setne-Khaemwese. These stories have Setne using his antiquarian knowledge to navigate ancient tombs, recovering magical books, and encountering the restless spirits of the dead. The influence of these stories on later Western fiction, and eventually Hollywood, is obvious.

The 1932 film ‘The Mummy’ likely took inspiration from one of the Setne stories. Photo: Public Domain

A man of enduring mystery

Into the modern era, Khaemwaset is a figure of both mystery and appeal. Egyptologists give him the honor of being one of them, while Ancient Egyptian appreciators of a more, shall we say, supernatural interest have likewise turned to Khaemwaset.

He appears to have been a person of interest in early 20th-century Western esoteric thought. In fact, this author found a number of blog posts from the depths of the internet suggesting that Khaemwaset still occasionally figures in what, out of respect for our crystal-owning readers, I will only describe as non-typical spiritual belief.

But to return to more stable ground, Khaemwaset presents yet one more great mystery to modern Egyptology.

It was Khaemwaset who founded the Serapium, a massive joint tomb for the sacred Apis bulls. These bulls were incredibly important to ancient Egyptian worship and fell under the purview of Ptah. Rather than entombing them in individual mausoleums, Khaemwaset had one massive tomb constructed, which was in service for centuries afterward.

In 1852, Auguste Mariette found the Serapium and began excavations. In the oldest section of the ruin, he found a store of treasures bearing the names of Khaemwaset and his father. Finally, he came upon a gilded coffin. Inside were nondescript remains and a man’s golden mask. For many years, Egyptologists believed this was the tomb and corpse of Khaemwaset.

But the body wasn’t his. In fact, it wasn’t even human; instead, it was yet another sacred bull. The actual tomb of Prince Khaemwaset, High Priest of Ptah and first Egyptologist, still lies undiscovered beneath the sands of Egypt.