Those who ski from Hercules Inlet to the South Pole may not be very interested in polar history, apart from professing an admiration for Shackleton. But those who travel the polar regions for years often become amateur historians. And it’s not just because the ordeals of explorers become more visceral when we’ve experienced a little of them ourselves.

So few people have traveled the Arctic and Antarctic, and things rot so slowly there, that explorers’ camps, skulls of murder victims, forensic evidence of what happened to famous expeditions, often lie undisturbed. History becomes alive. The more you know, the more you learn where other such places are, and the more you recognize what you see when you stumble across something.

I’m far from the only one to have discovered the past this way, but this is my experience. I hated history in high school. Rather than listen to the teacher drone on, I memorized rosters of sports teams, capitals of the U.S. states, pi to 50 decimal places. Not exactly electrifying, but even for a nerd like I, anything was better than history.

When I started traveling the Arctic, I carried this dislike with me. My love for the Arctic was about athletics and the landscape. It took a few years, but then I started to see things I couldn’t ignore.

Accidental discoveries

At first, my discoveries were accidental. I’d stumble across old signs of human presence. At first, I didn’t know what these sites were, so I researched them back home. I then became disappointed that I hadn’t thought to look them over more closely. So eventually, I did. In time, I even began to seek out these sites, as part of the Arctic travel experience.

In 1906, American explorer Robert Peary traveled the north coast of Ellesmere Island after another failed North Pole expedition. Near the northwest corner of the island, he and his two Inuit helpers climbed the hill above Cape Colgate. A photo in one of Peary’s books showed one of his helpers carrying one of the long bamboo wands that Peary used for marking supply depots.

When a sledding partner and I skied to Cape Colgate one year, we climbed the hill for an overview of the Arctic Ocean. There on top was the cairn that Peary’s party had built, with weathered fragments of bamboo still sticking out of it. I was no fan of Peary’s — he lied about almost every expedition he undertook — but this was incredibly exciting.

Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Most-visited Arctic site

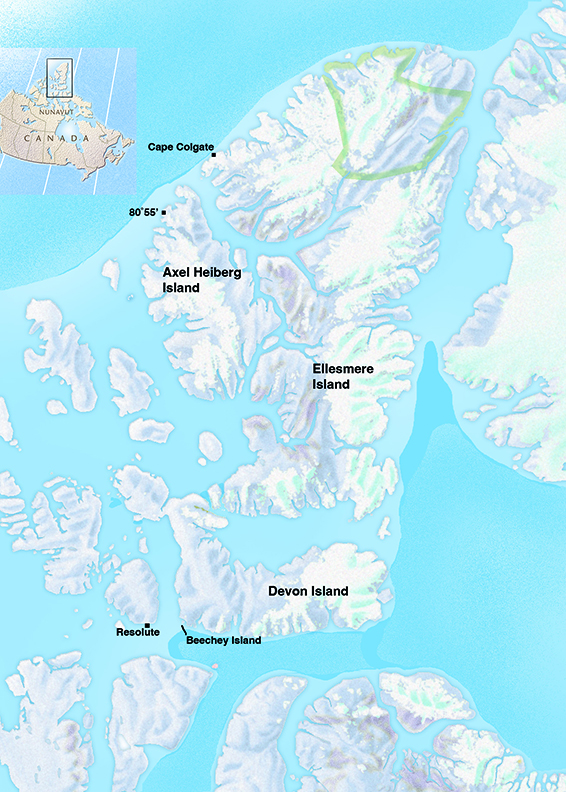

There is no question that the most-visited tourist site in the Arctic is Beechey Island, not far from the village of Resolute. There, in 1845-6, Sir John Franklin and his men overwintered. Three of them died. Their graves — plus the grave of a fourth man from a later search expedition — are still on the beach.

Beechey Island graves. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

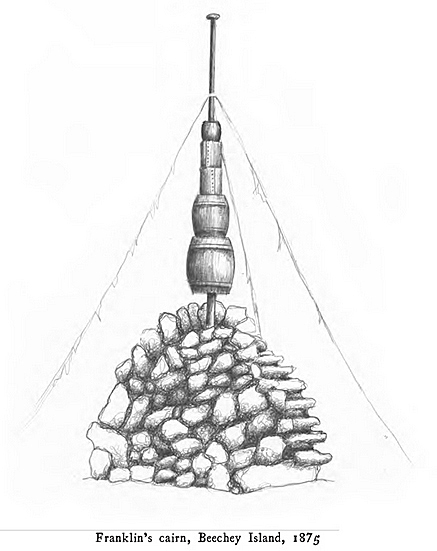

Thousands visit this place every summer. It is an obligatory stop for Arctic cruise ships. Far less well-known is that a half-hour hike away, on the top of the little island, Franklin built a giant cairn. It’s not visible from the beach because it was meant to be seen by ships sailing nearby Lancaster Sound.

That cairn, with its fallen pole and at least one surviving barrel, is still fairly intact. Because few eyeballs gaze at this site, it feels more pristine than the grave site down below. Summer fog often envelops Beechey Island, but curiously, the cairn’s location appears on the Navionics app, so it’s possible to find your way there even in zero visibility.

Franklin cairn, Beechey Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

The vanishing cairn

At first, a traveler learns about these places through the explorers’ popular books. I used to carry dozens of photocopied pages with me; now I just download their entire volumes on my phone.

Norwegian explorer Otto Sverdrup looms particularly large on Ellesmere Island, an area I specialized in for some time. That’s how I learned about his so-called end cairn at 80˚55′ on nearby Axel Heiberg Island. Here, Sverdrup left a note declaring sovereignty over the High Arctic islands for Norway. That cairn has never been found.

One year, a partner and I spent a day and a half looking for it. It’s in an area where any small pile of stones would be easily visible in the open landscape, and according to Sverdrup, this had been a sizeable construction. But it wasn’t there.

My theory — it’s just a theory — is that a 1932 Royal Canadian Mounted Police patrol in that area took the note and thoroughly dismantled the cairn, so that not even a remnant pile of stones remained. Canadian sovereignty over the region had been settled three years earlier, but the presence of a note giving those islands to the King of Norway might still have wigged out Canadian officials.

No sign of Sverdrup’s end cairn at 80˚55′ on northwestern Axel Heiberg Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Beyond popular accounts

As the historic passion grows, you become more serious about your sources. The explorers’ popular volumes are not detailed enough. You need their original trail journals and maps. These are rarely online. You have to visit archives, museums, and the rare book rooms of university libraries in other countries.

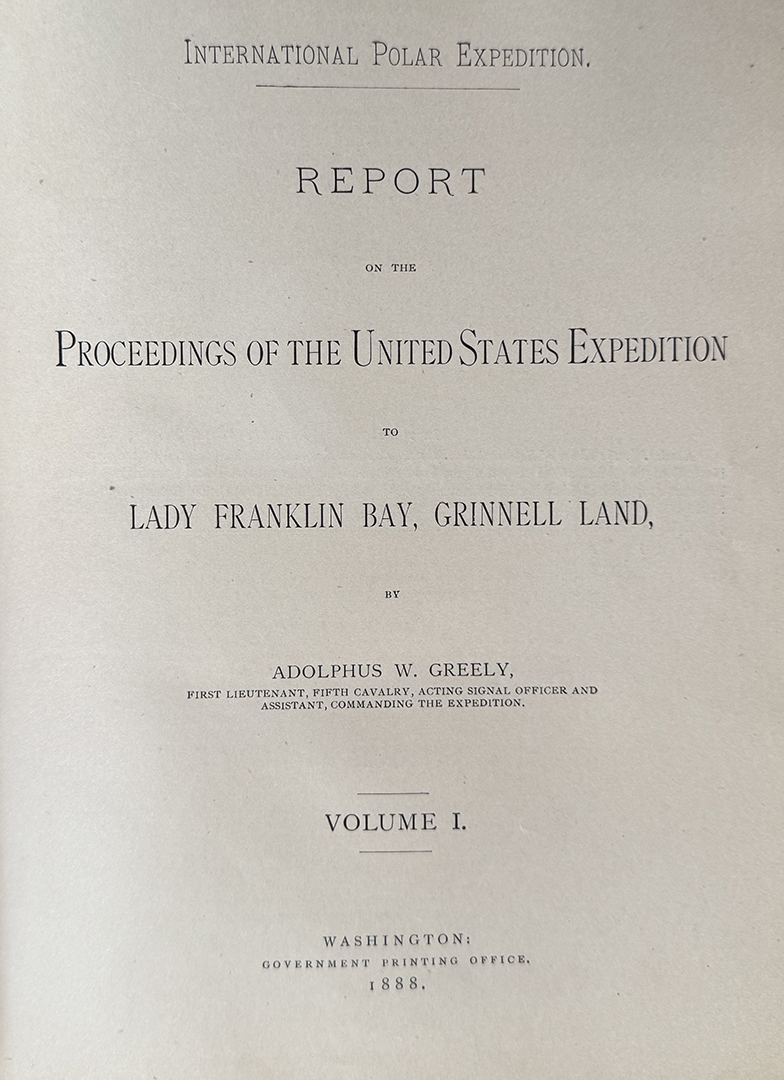

Washington, D.C.’s Library of Congress has Adolphus Greeley’s trail journal during his overland discovery of Lake Hazen, the world’s largest High Arctic lake. His small, neat, crimped writing hints at the precise man who got on the nerves of many of his men during that disastrous American expedition of 1881-84.

The Stefansson Collection at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire has two other journals from that expedition, including the long, vertical notebook of David Brainard, listing his fantasy meals during their eight-month starvation ordeal. It also has the journal of George Rice, another heroic figure, who perished in his tireless efforts on behalf of the crew. Such sources are less maps to particular sites than windows into the humanity of those explorers.

Apart from specific journals, the most useful source on the Greely expedition is the two-volume Proceedings, based on the Congressional investigation into the screw-ups that left 19 dead out of the 25 original members.

A five-pound albatross

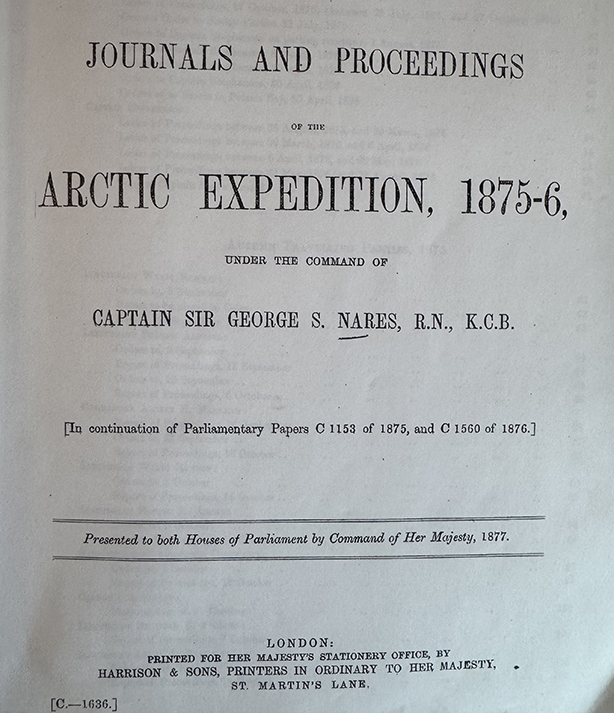

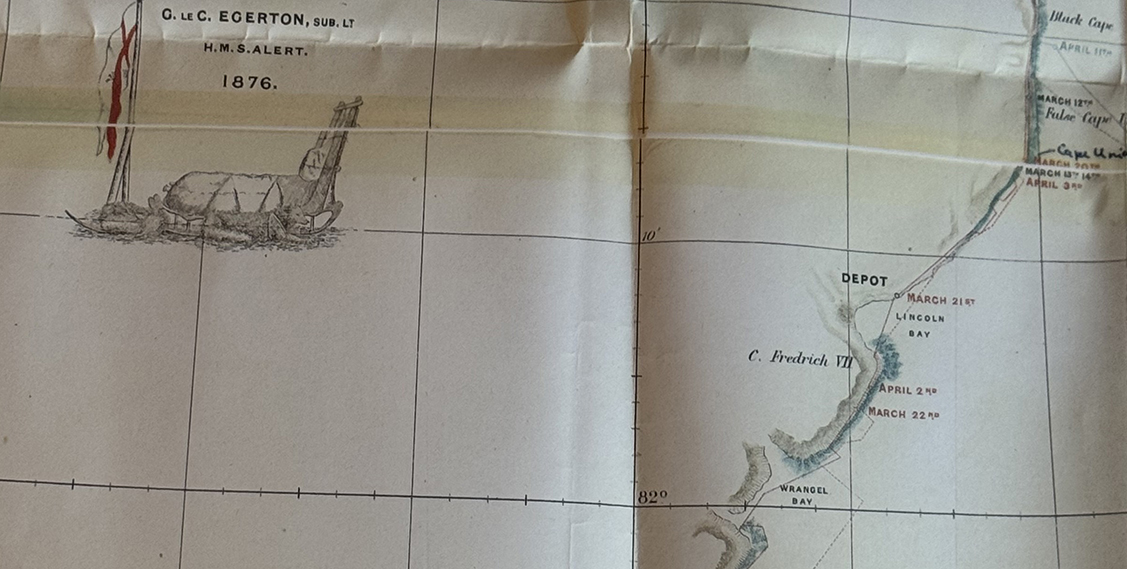

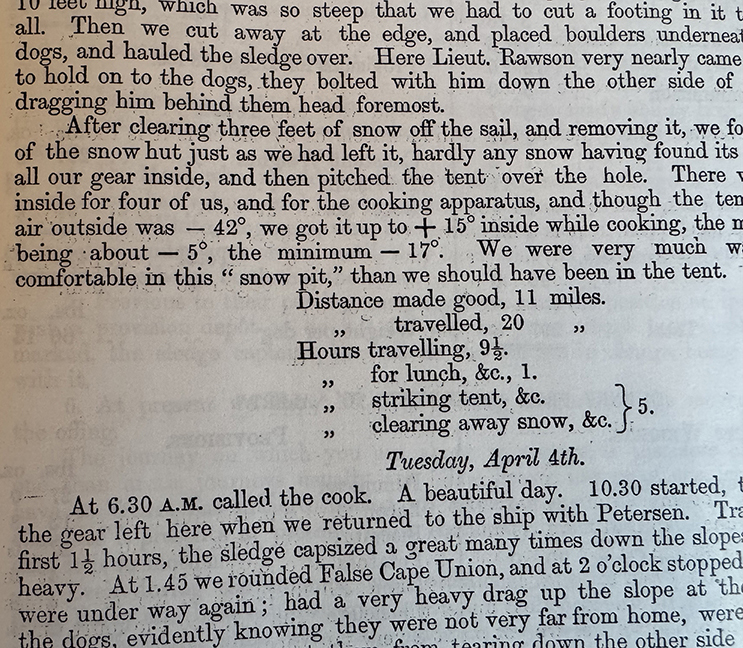

When I travel northeastern Ellesmere Island, even if I’m backpacking, I always carry the five-pound volume of Parliamentary Papers from the British Arctic Expedition under George Nares in 1875-6. Similar to the Greely Congressional Proceedings, its hundreds of pages are full of printed journals and detailed color maps of their routes, showing the locations of depots, camps, cairns, and so on.

Using that obscure volume — good luck finding it outside a private collection or somewhere like the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge — I’ve tracked down some of their depots on northern Ellesmere.

What do you do when you find them? Nothing, really. You take photos and GPS coordinates. You inventory. You poke around, looking for something unintentionally poignant. Then you continue your trek, utterly thrilled.

1876 Nares depot, Ellesmere Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Travelers have to develop to stay interested in travel. But this was quite a transformation for someone who used to memorize pi during history class.