It’s an oft-quoted fact that we know less about the bottom of the ocean than we do about space. And that’s true (from a certain viewpoint). But the top of the ocean can be equally mysterious, particularly when it comes screaming toward you at twice the height of the surrounding waves — seemingly out of the blue.

The phenomenon is called a rogue wave. These were long thought to be the stuff of maritime legend until improving technology allowed them to be recorded and studied for the first time. The Drapuner Wave, a 25.6m giant that struck an oil platform in the North Sea in the mid-1990s, was one of the first examples to be caught on camera.

Freak of nature

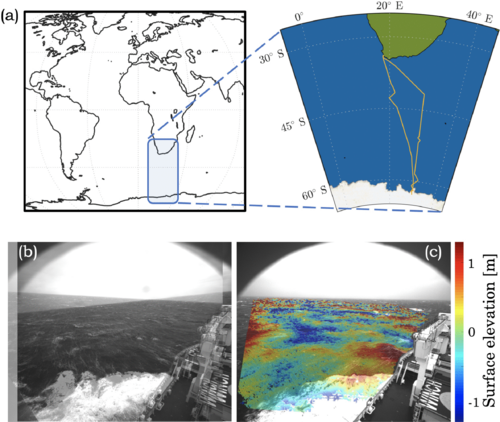

Efforts to understand these oceanic freaks of nature have continued ever since. One recent example is research published last month in the journal Physical Review Letters. Led by Alessandro Toffoli, a professor in ocean engineering at the University of Melbourne, the team ventured into the legendarily fierce Southern Sea with a boatload of 3D imaging equipment and — presumably — toiletry kits full of anti-nausea medication.

As Toffoli explains in a story published in The Conversation, current scientific consensus suggests that rogue waves arise from a combination of two factors. The first is an overlapping of multiple powerful waves — basically a “by your powers combined” type of situation. But the ocean is dynamic, and waves don’t overlap that way all that often.

The second factor is wind.

“But wind has seldom been considered in rogue wave analysis,” Toffoli wrote.

So, part of the team’s mission was to use the extremely bouncy journey to study wind and how it contributes to rogue wave generation.

But there’s a third factor that Toffoli and his comrades were even more interested in — one that might not bode well for how often rogue waves arise to terrorize sailors worldwide.

Young cannibals

Using 3D imaging techniques that mimic human vision, the team confirmed one of Toffoli’s long-held suspicions.

“When waves are steep and most of them have a similar amplitude, length and direction – another mechanism can trigger the formation of rogue waves,” he wrote.

“This mechanism involves an exchange of energy between waves that produces a ‘self-amplification,’ where one wave grows disproportionately at the expense of its neighbors.”

3D imaging software allowed a team of scientists to study rogue wave generation in the Southern Sea. Photo: A. Toffoli, et al, Physical Review Letters

Basically, the mere existence of a series of large waves can allow one of those waves to cannibalize energy from its sisters and become a rogue wave. The team’s paper reports that the expedition observed such occurrences once every six hours while sailing the Southern Sea.

“Our findings challenge previous thinking: that self-amplification doesn’t change the likelihood of rogue waves in the ocean,” Toffoli concluded.

It’s worth noting that self-amplification only occurred in “young seas,” which is to say, relatively new waves still prone to being influenced by wind (once a wave travels faster than the wind, wind ceases to be a factor).

Why does all this matter? Because as climate change ramps up, wind speeds and average wave heights in the Southern Sea are increasing.

In short, while scientists continue to try to understand rogue waves, what we know so far indicates that the forces that cause them are getting more powerful. And that’s something that doesn’t seem likely to change any time soon.