Over the past 30 years, scientists and those who prefer not to die in a nightmarish climate disaster have learned that climate change is as much a political struggle as a scientific one. But as the world’s most powerful people stall, deny, or ignore the problem, many now believe it is time to look for geoengineering solutions.

Geoegineering, or climate engineering, involves deliberately altering the Earth’s climate to counteract anthropogenic climate change. This possibility flared up again recently when a group of scientists and investors launched the Seabed Curtain Project.

The project proposes constructing a massive barrier will keep warm currents away from the Thwaites Glacier, forestalling its collapse and preventing over half a meter of sea level rise. The Thwaites Glacier is nicknamed the Doomsday Glacier because of its importance: If it goes, the entire West Antarctic ice sheet may soon follow.

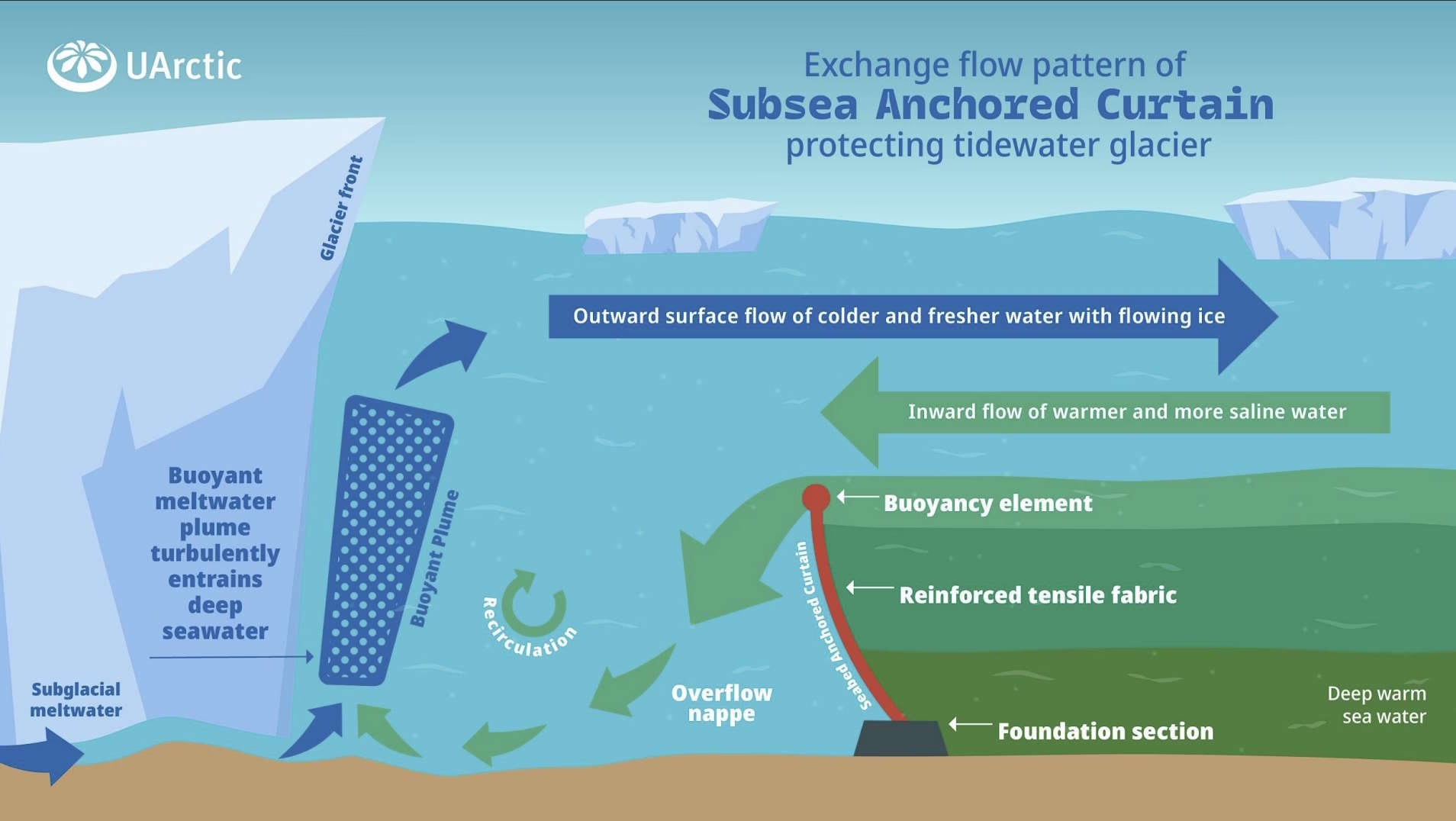

The idea is to build a sub-sea curtain 80km long and 150m high, sitting on the seabed 650m beneath the surface. The buoyant curtain would be anchored to heavy structures on the seafloor. Rather than one solid piece, the curtains would be made of many thin, overlapping panels of flexible material.

What material, exactly, is something the current proposal isn’t far enough along to know definitively. Their goal is to fund and deliver the research required to deploy the curtain by the year 2040.

A project diagram shows how the curtain would prevent warm, deep water from accelerating ice melt. Photo: The University of the Arctic

A bandaid solution?

Ice loss, warmer temperatures, and higher sea levels in the polar regions can act as positive feedbacks loops, quickly accelerating the changes — not just in those regions but elsewhere. Novel interventions on the Thwaites won’t solve this but could buy vital time.

However, climate engineering still has many detractors. The potential project’s initial cost is $40 to $80 billion, with $1-2 billion more per year for maintenance over the curtain’s 25-year lifespan.

In a recent paper, 41 climate scientists came out against such engineering. Massive, disruptive projects in the vulnerable polar regions, they argued, could have unforeseen consequences.

A seabed curtain, in particular, they wrote, is nearly impossible logistically. It requires building a delicate yet massive piece of infrastructure in “some of the world’s roughest seas…in ice-covered locations that even modern ice-strengthened vessels cannot always reach.”

Even if it could be done, they continue, a huge underwater wall would have unanticipated effects on marine ecosystems and oceanic circulation.

The Thwaites has lost over 1,000 billion tons of ice since 2000, and the rate of loss is accelerating. Whether or not a seabed curtain is part of the solution, it’s clear that some answer has to be found.