It came from the Oort Cloud, a giant web of floating miniature planets lying just beyond the edges of the solar system. It dazzled the skies above Chile for a handful of weeks. Now it’s gone for the next 600,000 years.

The Oort Cloud

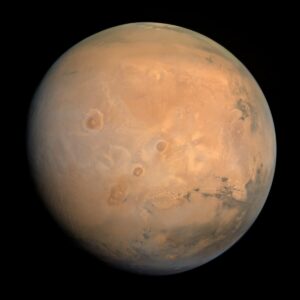

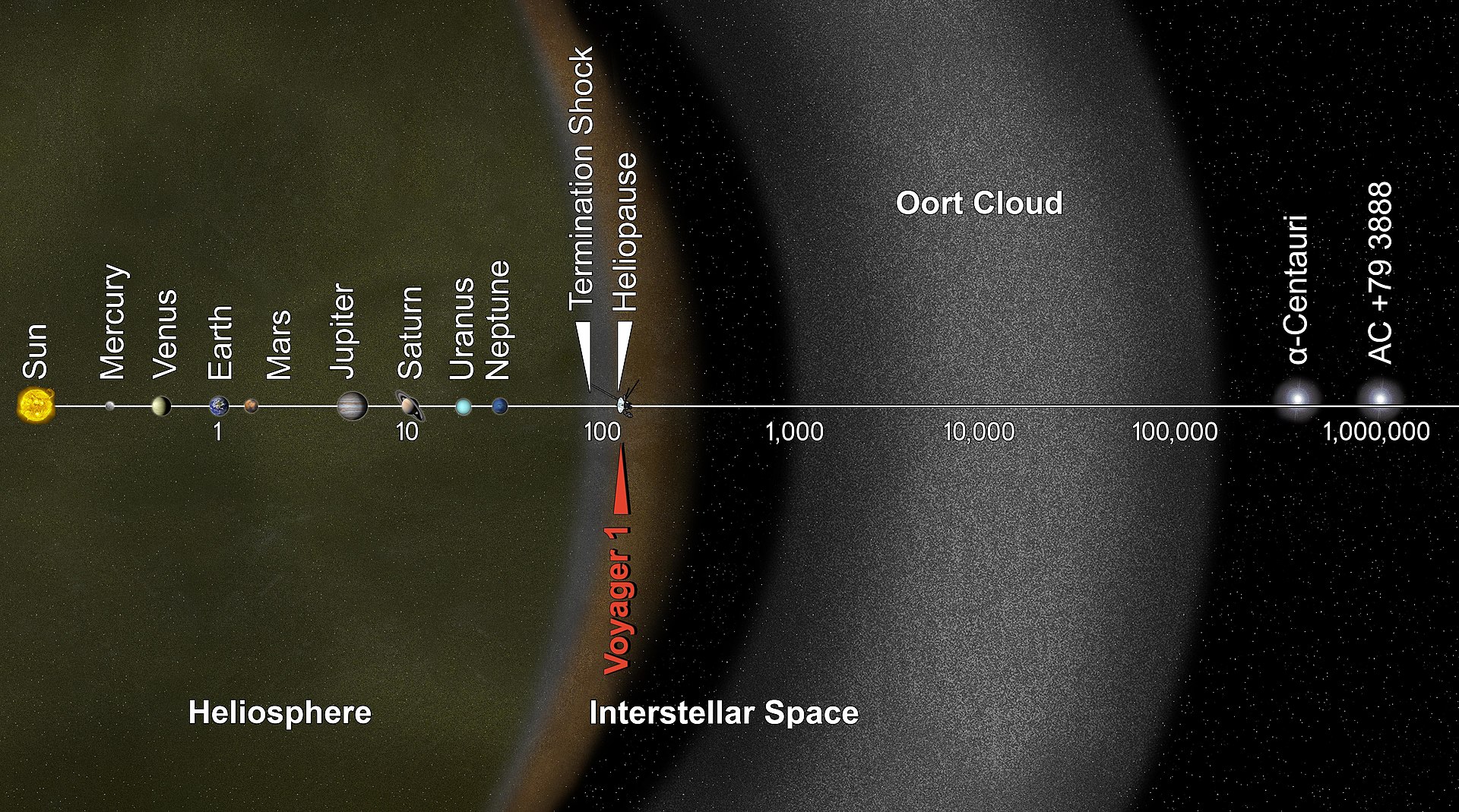

The Oort Cloud, technically, isn’t a confirmed place. It’s a theoretical location. Some comets orbit the Sun over hundreds of thousands or even millions of years. They must, therefore, call somewhere home. That place is the Oort Cloud, a massive reservoir of icy comets lying outside the boundary of the solar wind, too far for telescopes to see.

Many famous comets return within a generation. Halley’s Comet, for instance, will visit again in 2061. But when comets head in from the Oort Cloud, they won’t be back anytime soon.

The Oort Cloud lies just beyond the extent of the solar wind. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Early observations of the comet

Way back in April of 2024, observers at a small telescope in Chile reported a very faint speck hurtling toward the Sun. It was a comet, the icy siblings of asteroids, and it was 655 million kilometers away but approaching rapidly.

It took the name of the observatory that discovered it — ATLAS. And as 2024 turned to 2025, amateur astronomers started reporting that ATLAS was visible with the naked eye at night. Instead of a little dot barely visible with a telescope, it was now as bright as Polaris, the North Star.

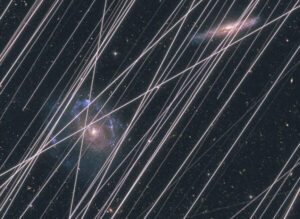

Amateur astronomers often provide most cometary observations and photography, such as this view of ATLAS (seen with a faint tail in the center of the photo) taken on January 3, 2025. Photo: Michael Mattiazzo

This sudden increase in brightness was caused by the disintegration of the comet’s surface. As the comet sped towards the Sun, the temperature increase evaporated large chunks of ice from its surface, feeding its outgassing tail and the hazy glow around its nucleus. But in early January of 2025, it hadn’t yet reached its full glory.

The Great Comet of 2025

On January 13, ATLAS entered an exclusive club: the list of comets within the last century that were visible to the naked eye during the day. At the time, it was passing through perihelion, the closest approach to the Sun. It was brighter than anything else in the southern sky, including the planets.

Astrophotographers snapped stunning photos of its tails, one comprised of heavy particles and the other of light gases. An astronaut on the ISS snapped a photo of it through the space station windows. And NASA used a telescope device called a coronagraph to block out the Sun’s light, allowing sensitive cameras to observe the comet without being blinded.

The comet on January 21 over Punta de Lobos, Chile. Photo: Wikimedia

The comet descends over the Earth’s atmosphere, viewed from the ISS on January 10. Photo: Иван Вагнер/Роскосмос/ТАСС

A coronagraph blocks out the Sun’s light in this timelapse video of perihelion. The comet’s tail is so bright that it is causing the sensors to glitch, resulting in the horizontal spikes. Photo: NASA/ESA/SOHO/LASCO/K. Battams

Goodbye, ATLAS

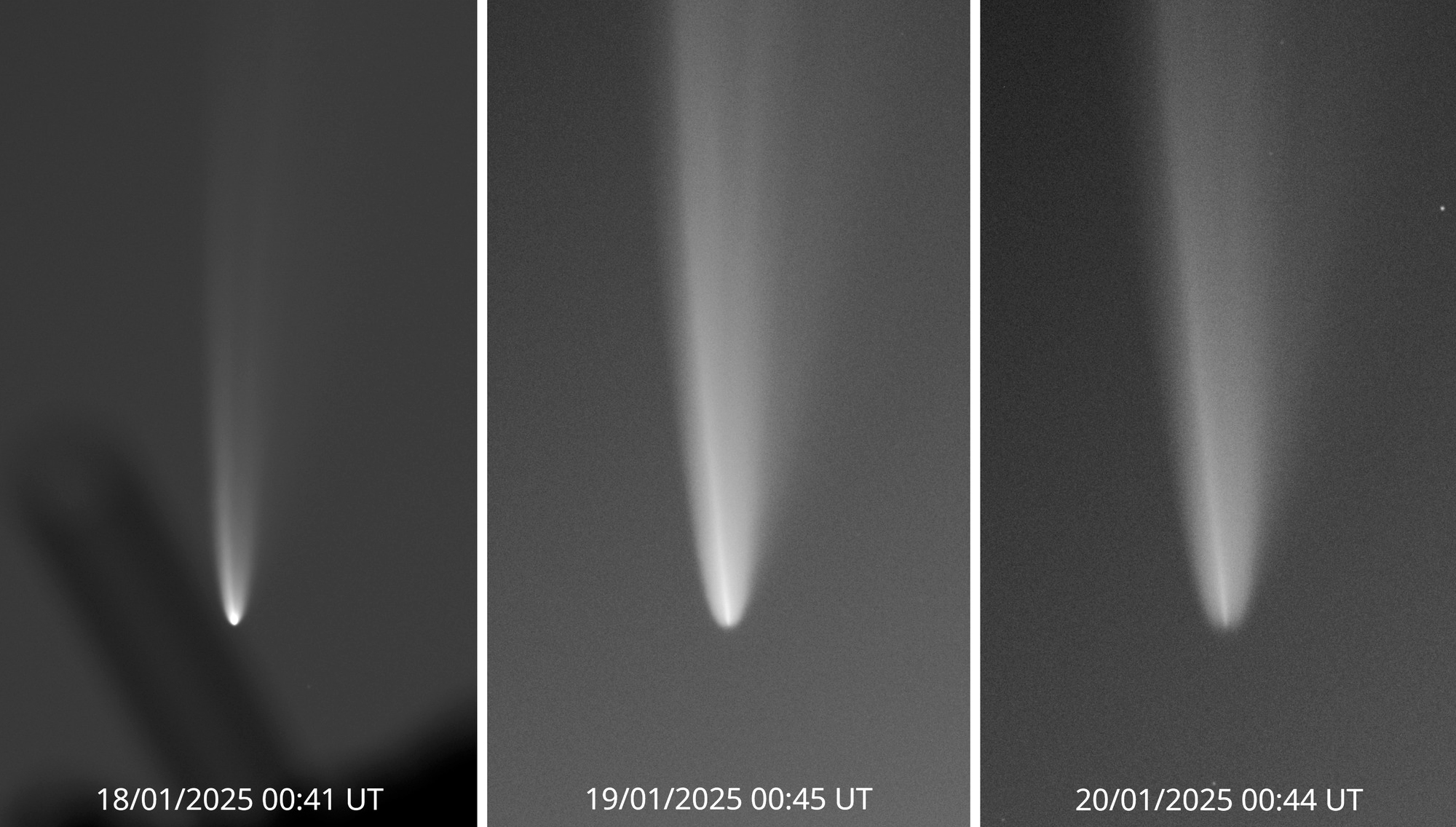

ATLAS is heading away from us, but not unscathed. On January 19, the bright little speck of its nucleus vanished, suggesting that the comet fragmented after its passage around the Sun. What’s left is a ghost: tails still streaming across the sky in the wake of debris that soon may disintegrate entirely. We’ll have to wait half a million years to see if any part of it survived its vacation to the center of the solar system.

On January 19 (the middle photo), ATLAS’ nucleus disappears. Photo: Lionel Majzik

The comet on January 21, seen from Cerro Paranal in Chile. The Very Large Telescope is on the left. Photo: Florentin Millour

Gas and dust particles created multiple tails in the ATLAS comet. Photo: Abel de Burgos Sierra/ESO