For decades, the disappearance of dinosaurs has been tied to the Chicxulub asteroid, whose crater lies partly beneath Mexico’x Yucatan Peninsula. But new research has revealed that there were at least two dinosaur-killing asteroids. The impact crater of the second one lies unseen, 300m under the floor of the Atlantic Ocean.

Illustration: Wikipedia

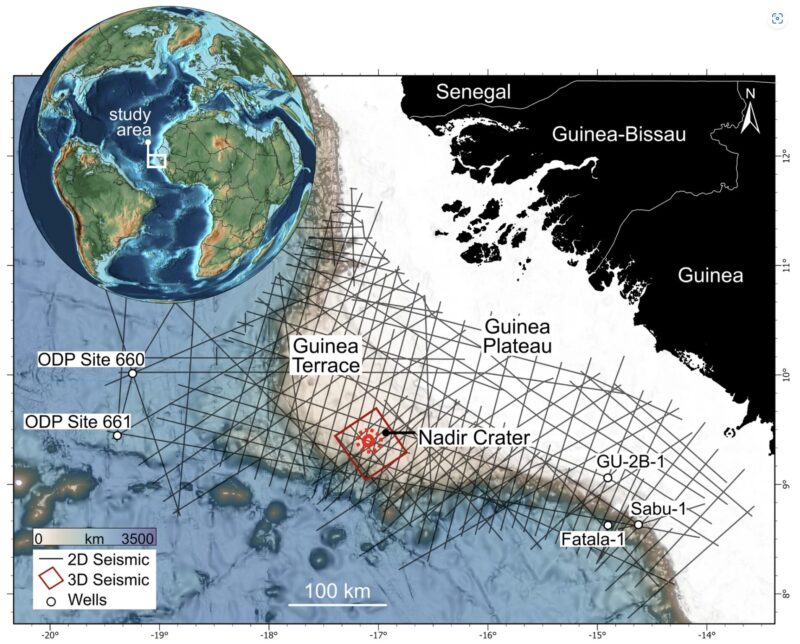

Discovered in 2022, the Nadir crater lies off the coast of Guinea, West Africa. The 400m-wide asteroid created a crater 8.5km in diameter. The exact timing of the impact is unknown, although it struck at the end of the Cretaceous period, around the same time as the asteroid that created the 200km-wide Chicxulub crater. Though the Nadir crater is much smaller, the space rock that made it still slammed into the Earth at 72,000kph.

The location of the crater. Image: Nicholson et al., 2024

From new images of the crater, researchers have been able to piece together what happened in the minutes after impact. The asteroid hit with such force that it triggered a series of events that likely added to the dinosaur’s mass extinction event. The initial impact liquified underwater sediments, causing faults in the seabed, landslides that extended far beyond the edge of the crater, and a huge 800m-high tsunami to tear across the Atlantic Ocean.

Uisden Nicholson discovered the Nadir crater in 2022. He was studying seismic data from the Atlantic Ocean off West Africa when he stumbled across it. He always thought an asteroid had created the crater, but now he had seismic data to prove it.

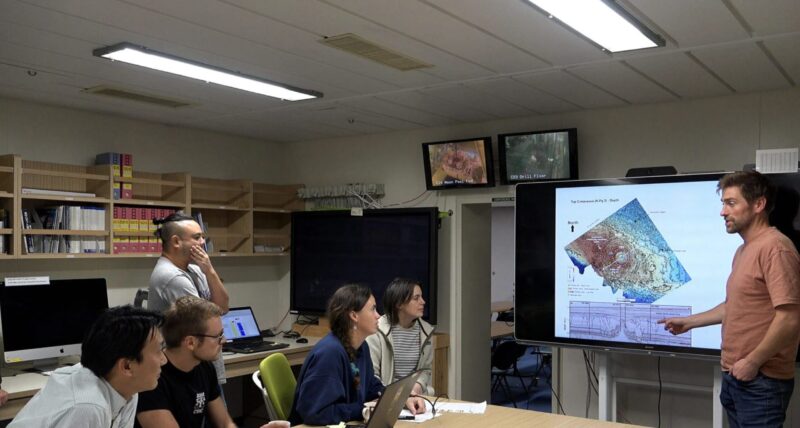

“There are around 20 confirmed marine craters worldwide, and none of them has been captured in anything close to this level of detail,” Nicholson commented. “It’s exquisite.”

Uisdean Nicholson presents his findings. Photo: Heriot-Watt University

Like an ultrasound

He compared the new and improved imaging to that of a pregnancy ultrasound:

A few generations ago, the ultrasound showed a grainy blob. Now you can see the baby’s features in 3D, in incredible detail, including all the internal organs. We’ve gone from 2D, fuzzy imaging to amazing high-resolution imaging of the Nadir Crater. The new images paint a picture of the catastrophic event.

The advanced imaging also lets us examine other impact events in more detail and consider how they might have affected Earth’s evolution.

“Most craters on the surface of the Earth have eroded over time, but we can use seismic data and drill cores to look at what is going on underneath them,” said co-author Veronica Bray. “Some craters on other planets are in almost pristine condition but we can only see the surface layer. This new seismic imaging allows researchers to look at the surface and everything underneath it. It’s a startlingly good look at an impact crater.”