The two Nepali teams currently attempting to open a new commercial route on the south side of Cho Oyu have progressed surprisingly quickly. This, despite the harsh winter weather and technical difficulty on the Nepali side of the mountain.

Both teams say that they’re ready for a summit push once conditions permit. It is not unlikely that they will end up trying to reach the 8,201m summit at the same time, via their different routes.

The question is — exactly where are they climbing?

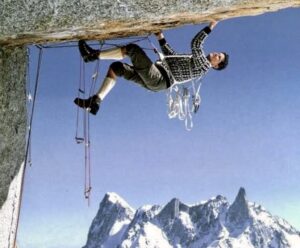

Gelje Sherpa’s team on the route. Photo: Lakpa Dendi

Few details

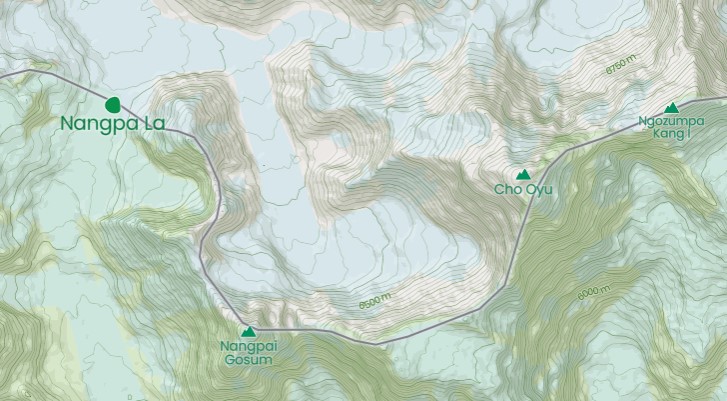

Gelje originally told Stefan Nestler that he wanted to approach the peak “not from the Gokyo side, but from the Nangpa La side (the pass between Nepal and Tibet).”

That is, “over the flank of the 7,000’er Nangpa Gosum, which is connected by a ridge to the highest point of Cho Oyu,” Nestler added.

Nangpa La and Cho Oyu area. Image: Mapcarta

Gelje Sherpa is a respected climber who is trying to become the youngest 14×8,000m summiter. He was also, impressively, one of the 10 who summited K2 in winter a year ago.

As with any other Himalayan climber, we take him at his word, but there has been some recent confusion or obfuscation about the route. Two days ago, he published three screenshots from his tracking device. They showed that their route actually followed a much more direct line up Cho Oyu from Ngozumpa Glacier, toward the col separating Cho Oyu (to the west) and Ngozumpa Kang I (7,916m), also known as Tenzing Peak (after Tenzing Norgay).

Simulation by PeakVisor.com of the view of Cho Oyu from the col to the east. The col separates Cho Oyu from Tenzing Peak, which is not visible in the illustration.

We asked the geolocation and GPS tracking experts at RaceTracker to check the route that Gelje and his team are following. Based on Gelje’s tracker screenshots, the topography, and Google Earth, this is their conclusion:

Gelje Sherpa’s route on Google Earth, based on the screenshots that he shared on IG. Compiled by RaceTracker.es

Credit: RaceTracker.es

Credit: RaceTracker.es

All Cho Oyu routes compiled by Animal de Ruta blog. The ones in Nepal are numbers 15, by Urubko and Dedeshko, 4 by the winter Polish team, 2 the Austrian ascent of 1978 and 8 the Russian line along the East Ridge. The approximate line followed by Gelje is marked in a thicker red line.

Mixed messages

There also seems to be some confusion about the highest point that the climbers reached before retreating to Base Camp. Gelje posted a screenshot of a zoomed-in track. There was no overview, but the data at the bottom of the screenshot read 7,409.72m.

Fellow ExWeb writer @KrisAnnapurna noted that this altitude was remarkably higher than the altitude cited on other screenshots. We did some research, again with the help of RaceTracker. They located the exact point of the last screenshot and concluded that it corresponds to 6,900m, not 7,400m.

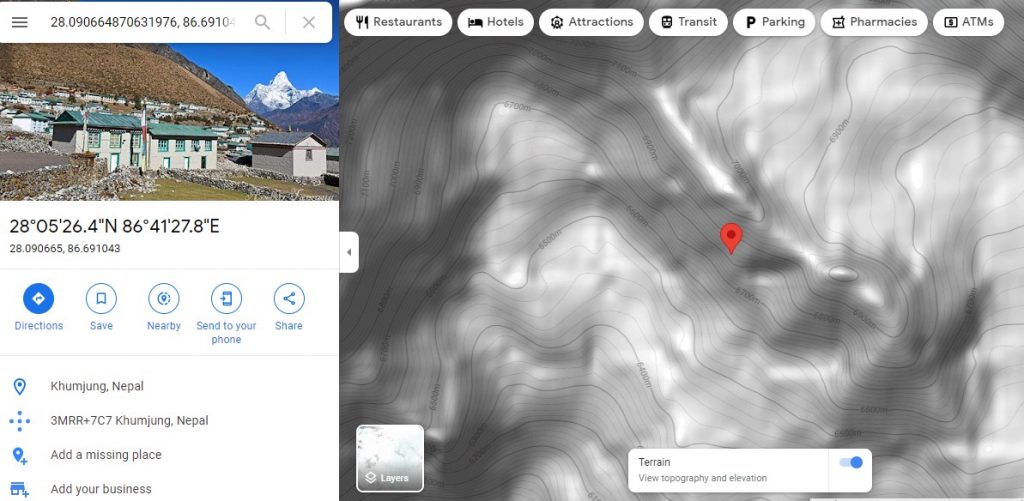

We have reproduced their results below. Interested readers can check it for themselves: Go to coordinates 28.090664870631976, 86.69104276103228 on Google Maps, compare the features (select the satellite layer) with the tracker, then change to terrain layer and check the altitude.

Coordinates on Google Maps, satellite layer.

Same coordinates on the terrain layer, showing an altitude of approximately 6,815m. Image: Google Maps

Gelje’s position, as shown on the screenshot that he posted. Translated onto Google Earth, which shows the correct altitude at the bottom. Racetracker.es

This does not imply that Gelje and his team are being misleading about the highest point that they reached. There are many reasons why the climbers could have gone higher than their tracker registered. They could have shut it off to conserve battery power, for example. But it does mean that Gelje’s initial screenshot above has been combined with data from a higher altitude. Hopefully, the climbing team will be able to explain these irregularities when they return.

The yellow line marks 7,400m. The red line is Gelje’s actual track. The blue dot shows Gelje’s high point, as shown in the tracker screenshot he shared on social media. Photo: Racetracker.es

Earlier today, Gelje’s teammate Lakpa Dendi wrote that they had to retreat in rapidly worsening weather from 7,200m.

The route ahead

Gelje Sherpa’s team is heading for the col between Cho Oyu and Tenzing Peak. (See the last image above.) Once at the col, they will have to follow the long East Ridge toward the main summit. That is, unless they find a shortcut up the face, but this is unlikely, considering the almost vertical terrain.

The aerial view (shot by Gelje Sherpa from a helicopter) shows Cho Oyu’s main summit and the East Ridge to its right. Tenzing Peak lies unseen, to the right of the image.

Cho Oyu north side from Tibet. Tenzing Peak is the flattish one on the left. Photo: Wikipedia

Following Mingma G’s proposed route

Gelje Sherpa’s team is actually following one of the two routes that Mingma G presented to the government of Nepal when they promised to fund a local expedition seeking to open business on Cho Oyu’s Nepali side.

Mingma G shared these details with ExplorersWeb back in late November. He proposed two possible routes up the SE Face. Both aim for the difficult East Ridge. Gelje is leading his team up the aqua-colored line identified as Route 2 in the legend.

Satellite images with the two possible route options on Cho Oyu, courtesy of Mingma G. Gelje’s team seems to be following Route 2.

Mingma G. also detailed the crux of the climb, which lies further than the highest point that the current expedition reached: the East Ridge. That ridge has been already climbed but never repeated.

The Southeast Face+East Ridge of Cho Oyu had thwarted several expeditions before an elite Russian team finally succeeded in October 1991. In her report, Elizabeth Hawley deemed the East Ridge “formidable” and mentioned a “70-metre-deep gap with 80° rock on its sides at a very high altitude.”

On their no-O2 summit push, the five Russians set high camp at 6,900m and a bivouac on the ridge at 7,900m. Sadly, falling rock killed one climber during the descent after the successful climb.

Gelje mentioned that they intend to set Camp 3 at 7,800m, which places it above the col. Later, we hope to clear up whether this is a new route, a variation, or a repetition.

Pioneer Adventure’s route

The second team on Cho Oyu, launched by Pioneer Adventure, has shared their climbing route with ExplorersWeb. It follows a totally different route, from the south.

Pioneer Adventure’s projected route up Cho Oyu, led by Mingma Dorchi Sherpa. Photo: Pioneer Adventure

We compared the map provided by Pioneer Adventure with a topographic map of Cho Oyu routes compiled by Animal de Ruta’s mountaineering blog. We found two options that might be similar to Pioneer Adventure’s route.

At first glance, it seems to match the route opened up the southeast buttress by the Polish Ice Warriors in winter 1985. That team, led by Andrzej Zawada, set up five camps and succeeded despite relentless bad weather. Maciej Berbeka and Maciej Pawlikowski summited on February 12, followed by Zygmunt A. Heinrich and Jerzy Kukuczka three days later. It was Kukuczka’s second winter first ascent of an 8,000’er that season, he had summited Dhaulagiri on January 21.

The 1985 Polish winter route up Cho Oyu’s south ridge. Route line: Animal De Ruta

However, it is also possible that the map provided by the Pioneer Adventure team shows a line much further west, up the SSW ridge.

A second possibility: the route planned by the Pioneer Adventure team may go up the Southwest Ridge, green line above overlaid on the Animal de Ruta blog.

According to Animal de Ruta’s blog, the SSW ridge, on the border with Tibet, has never been climbed. This isn’t surprising: It is difficult and extremely long. The ridge stretches 6.5km and gains 2,900 vertical metres. There is more than one possible access point for the SSW ridge.

We are waiting for Pioneer Adventure’s climbing team to confirm the exact line they are climbing.

Today’s update:

Gelje’s team is in Base Camp, resting and preparing for the summit push. Elite Exped ground manager Ashok Wenja Rai, who is working with Gelje, reports that they have tentatively scheduled their summit push for February 24 to 27.

Gelje Sherpa. Photo: Gelje Sherpa/Instagram

A spokesperson at Pioneer Adventure told ExplorersWeb that their team might go up at the same time. We may therefore see two Nepali teams racing for the summit of Cho Oyu from different angles. However, Pioneer’s team is currently facing an unexpected problem.

“It seems we miscalculated the distance,” the spokesperson told ExplorersWeb. “The ropes we sent at the beginning [ran out], so we delivered new ropes today. The team’s original plan was to set up Camp 2 yesterday and fix to Camp 3 today. [Instead] they hope to fix Camp 2 tomorrow.”

At least, the weather has been clear all day.

Denis Urubko weighs in

The Nepali lines apparently lie to either side of Denis Urubko and Boris Dedeshko’s 2009 direct route up the peak’s SE Face. The highly difficult line, climbed in pure alpine style without oxygen, was the last opened on Cho Oyu’s Nepal side.

Denis Urubko and Boris Dedeshko’s 2009 route. Photo: RussianClimb

Urubko returned to Cho Oyu’s south side in 2013 to acclimatize before attempting Everest with Alexey Bolotov. Urubko’s educated opinion:

“That face is very steep and rather humid because of its [southerly] orientation. It also features many rocky pinnacles, and avalanches pose a serious threat. All these factors minimize the chance of success. Yet I respect the desire of Nepali teams to find a safe line, which down the road could help the Khumbu economy. Is it possible? In my humble opinion, yes, it is.”

As for the routes themselves, Urubko suggests that according to the map provided, the Pioneer team may be climbing a variation of the Polish route, but from the right side of the plateau. “As for the Russian route up the East Ridge,” he says, “the crack on the ridge is technically difficult and risky — definitely not for clients.”

Urubko adds that winter conditions are radically different than the more dangerous situation in spring or fall when the clients would come.

“[In warmer conditions], that face is unpredictable,” he warned. “Is it worth putting clients through such risks? It would be more effective and safer to build a tunnel to the top, as on the Eiger! Or to concentrate on the business of the rest of 8,000ers…This climb may show the Nepalis’ strength to the world, but [doing it] once should be enough.”