A new study has revealed that Stonehenge’s six-tonne altar stone came from even further afield than archaeologists thought. Neolithic people somehow moved the enormous stone roughly 750km from northeastern Scotland to southwestern England.

A new mystery

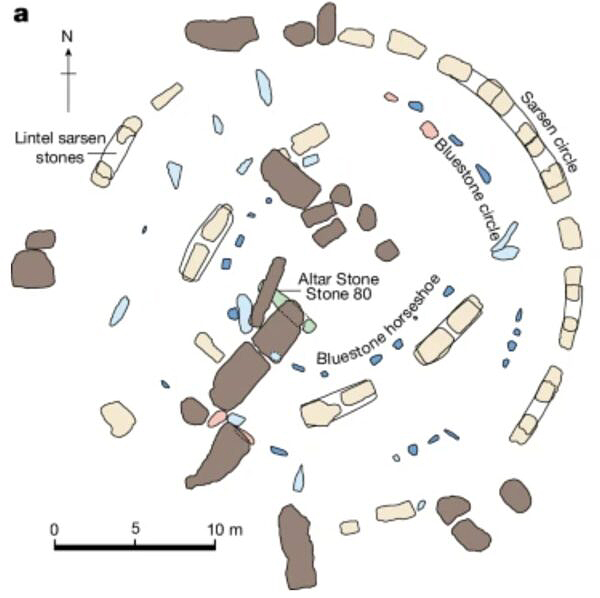

The altar stone lies at the heart of Stonehenge, buried in the center of the circle. Much like the Neolithic site it belongs to, its purpose remains a mystery.

The majority of the Stonehenge Circle is made of either sarsen (silicified sandstone blocks) or bluestone (a type of fine-grained sandstone). The sarsen stones are from the nearby West Woods. But the bluestones come from the Preseli Hills in southwest Wales, already a monumental distance to transport heavy loads with primitive technology.

The sandstone altar stone is the biggest bluestone, and researchers had assumed it came from the same corner of Wales. Fresh geological fingerprinting shows that this is not the case.

The layout of Stonehenge. Image: Clarke et al., 2024

The altar stone was added to the site during the second construction phase between 2620 and 2480 BC. Last year, Nick Pearce, a professor of geography and earth sciences at Aberystwyth University, declared that the stone was not from Wales. Now, an international team from Wales, Australia, and England has pinpointed its original location in northern Scotland.

“I don’t think I’ll be forgiven by people back home,” lead author Anthony Clarke, who is from Wales, told the BBC.

Image: Google Maps

A shocking result

Stonehenge is a World Heritage Site, and researchers cannot chip away at the stones. Instead, they have to use historical samples. One of the study’s samples was taken in the 1840s, the other in the 1920s. The team studied the mineral grains in the stone fragments to analyze their age. The chemical fingerprint showed that some minerals are two billion years old, while others are around 450 million years old.

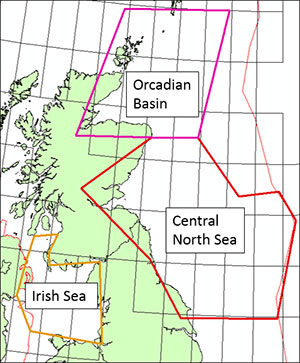

The team compared this chemical fingerprint with rock and sediment from across Europe. The results match the Old Red Sandstone from the Orcadian Basin, a depression of sedimentary rock in northern Scotland. The basin stretches from Inverness to the Orkney Islands.

“This is a genuinely shocking result,” co-author Robert Ixer said.

The findings provide fresh insight into the Neolithic period.

“Our discovery of the Altar Stone’s origins highlights a significant level of societal coordination during the Neolithic period and helps paint a fascinating picture of prehistoric Britain,” co-author Chris Kirkland commented.

The Orcadian Basin in northern Scotland. Image: British Geological Survey

How, and why?

How and why Neolithic people transported the rock remains a fascinating mystery. Speaking to The Washington Post, the authors said that this is a puzzle for future generations of archaeologists to solve, if it can be solved at all.

A similar mystery relating to how the ancient Egyptians moved the giant blocks from the quarry to the pyramids was recently solved using a combination of historical maps, sediment coring, geophysical surveys, and radar satellite imagery. It turns out that a 64km-long branch of the Nile that vanished thousands of years ago was still flowing when Egyptians built the 31 pyramids. They evidently barged the blocks down the Nile to the sites.

Stonehenge experts also believe that transport via boat or raft is likely. “Transporting such massive cargo overland from Scotland to southern England would have been extremely challenging, indicating a likely marine shipping route along the coast of Britain,” Kirkland explained.

Stonehenge is at least 55km from the ocean, so even a water route required a lot of dragging at the end to move it into place.

While Stonehenge has been extensively studied, it is still capable of surprising researchers.