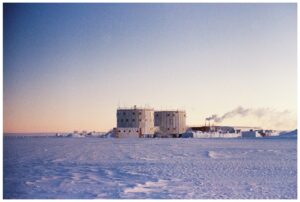

The Amundsen-Scott station at the South Pole is recording a heat wave — measuring average days of -37˚C instead of the typical -53.7˚ average.

While it’s not unusual for temps at the Pole to tick upward from time to time, scientists say the severity and duration of this event is part of a global pattern of unusual weather this season: from record-breaking snowpack in the American West to the second-warmest winter in Europe.

“The culprit for the unusually high temperatures [at the South Pole] is likely to be a shift in the southern jet stream, the undulating high-altitude current that carries warm air masses far into the south while bringing colder air masses farther north,” wrote Dr. Michael Wenger in a recent post on Polar Journal.

The heat wave that started on March 25 at South Pole Station continues

The montly average will be above the reference 1991-2020 (-53.7 °C) for the first time since August 2022 pic.twitter.com/KeR3Tyniyq

— Stefano Di Battista (@pinturicchio_60) March 27, 2023

Atmospheric rivers bring heat and moisture, Wenger continued. As of this writing, a glance at the South Pole Station webcam bolstered his thesis: It showed the cloudy skies accompanying such rivers.

Wenger also pointed out that February saw the lowest Antarctic sea ice levels on record, with ice continuing to decline in March.

Taken together, the trends are “another shot across the bow that shows that climate is going off the rails globally,” the scientist concluded. If there’s a silver lining, it’s this: The temperatures aren’t as warm as those recorded last year, when Concordia station reported a relatively sweltering -11˚C.

What’s cooler than being cool? Ice cold.

On the other end of the Antarctic weather spectrum is the kind of mind-boggling cold the continent is famous for. A good example is the conditions experienced by three members of Robert Scott’s 1911 Antarctic expedition.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, Henry Bowers, and Bill Wilson split off from the primary expedition in June 1911 to collect emperor penguin eggs. On their journey, they camped in -60.5˚C (-77˚F) — still a record low for a night spent in the open.

“The day lives in my memory as that on which I found out that records are not worth making,” Cherry-Garrard later wrote in his great classic memoir of the ordeal, “The Worst Journey in the World.”

If only some contemporary Antarctic travelers took this to heart and were less concerned with records.

Anyway, as fate would have it, the egg quest so weakened Cherry-Garrard that he didn’t accompany Scott on the final push for the pole. Scott and four others (including Bowers and Wilson, but minus Cherry-Garrard) did make it to the South Pole, but their hopes of being the first there were dashed. A Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen beat them by 34 days — a fact Scott’s team only realized upon discovering a flag, gear, and note the Norwegians left behind at the Pole.

“Great God! This is an awful place,” Scott wrote in his journal. “Well, it is something to have got here.”

The five men began the multi-week return journey. But their frigid trek ended when the men perished 18km from One Ton Depot, a supply cache they’d created earlier in the expedition.

Would Scott’s group have made it these days, in the relatively balmy climes? Hard to say, but it’s at least certain that Cherry-Garrard did not want it any colder.