Space is packed with hazards and health risks, and researchers have spent decades discovering what space travel does to the human body (answer: nothing good). But a new study suggests that the effects are more fundamental than we realized. Spending time in space can actually speed up the physical aging process on a cellular level.

Cells in space

The recent study, funded by NASA and conducted by the University of California San Diego’s Sanford Stem Cell Institute (UCSD), examined the effects of space travel on human stem cells.

Specifically, these were human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, or HSPCs. Stem cells are cells that are not yet fully differentiated, meaning they can become various types of cell. HSPCs can become blood cells and are an important part of the immune system and vascular health.

Dr. Catriona Jamieson and her team in the lab, preparing for the experiment in space aging. Photo: Kyle Dykes/UCSD Health Sciences

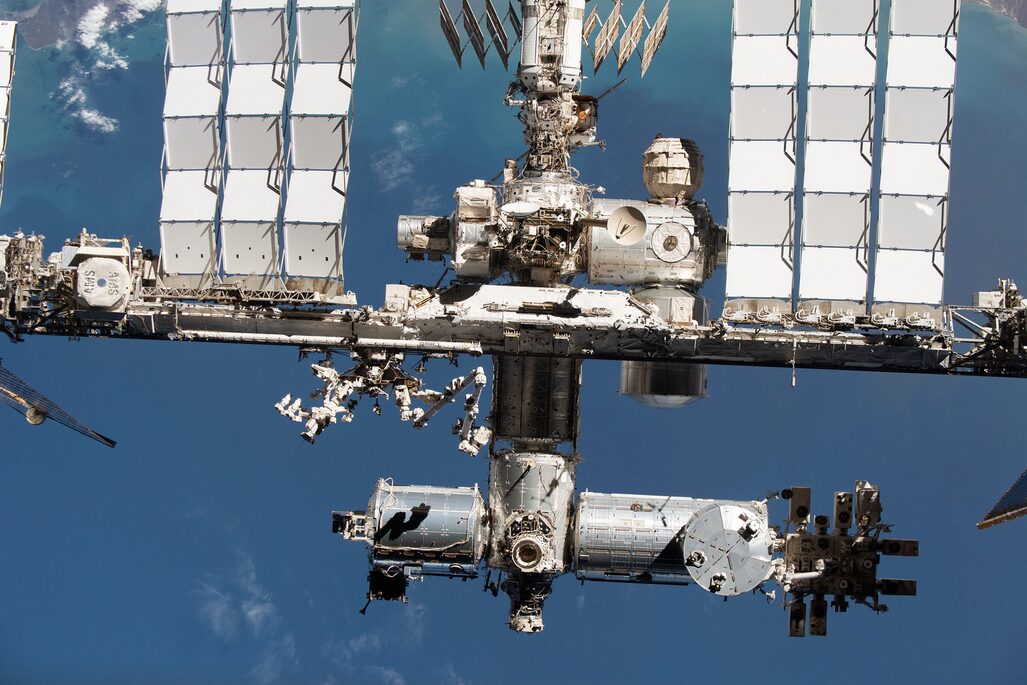

SpaceX periodically sends craft to the International Space Station on resupply missions. For this experiment, the UCSD team, led by Dr. Catriona Jamieson, sent some cells up with them. The scientists cultured the cells inside a “nanobioreactor” of the team’s own invention. The nanobioreactor kept the HSPCs in a stable environment and monitored a number of important health indicators.

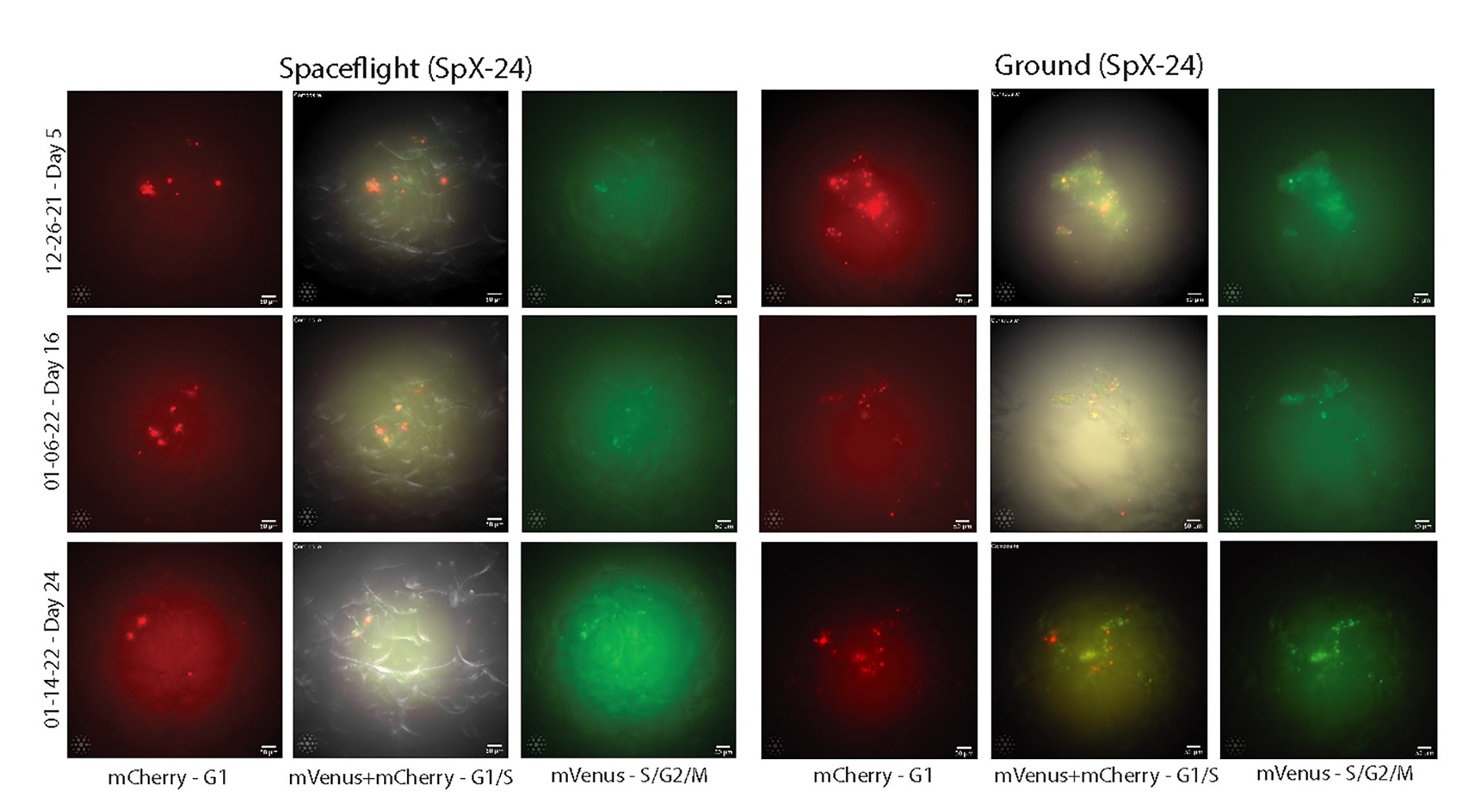

The cells spent 32 to 45 days in space across several different supply missions. Once they got home, researchers compared them to a control group that never left Earth.

You can see a distinct difference from the control in the fluorescent images of the cell cultures. Photo: Jamieson et al

Cells hate being in space

The cells that went to space came back changed. They were more vulnerable to mutations, were less able to make new, healthy cells, and were losing their DNA protection more quickly.

In some ways, their findings corroborated earlier findings. Most importantly, the famous “twins study,” where astronaut Scott Kelly went to space while his brother Mark stayed home. The stem cell study confirmed what the Kelly brothers demonstrated: Space is bad for telomeres.

Telomeres are a protective cap at the end of your DNA. When DNA is copied, a little bit at the end is chopped off. The telomeres get chopped off first, so you don’t lose anything important — until you run out of telomeres. Scientists believe that losing your telomeres is an important element of the aging process. It seems that space travel inhibits telomere maintenance.

Exposure to damaging ionizing radiation in space also made the cells more likely to mutate. We’ve been aware of possible increased cancer risks for astronauts for a long time, but this new evidence will help provide direction for future research.

The cells showed broader signs of stress, wear, and aging as a result of space. The mitochondria (the powerhouse of the cell) exhibited stress responses, which could decrease immune health. The cells became more active, burning through stored-up energy, inhibiting their ability to recover.

Scott Kelly and Mark Kelly. Photo: Derek Storm/NASA

Good news for the HSPCs (and space enjoyers)

It isn’t all bad news. The research team kept monitoring the cells after they returned to Earth and found they showed signs of recovery. After spending 12 days cultured on healthy young bone marrow stromal layers, the cells were perking up and increasing their capacity for self-renewal.

This data confirms at a cellular level much of what the twins study suggested. Once Mark Kelly returned to Earth, many of the negative effects of time in space reversed, at least partially. But, as the study’s authors warn, the effects of longer-term space travel may be more dramatic and more permanent.

As we continue to send people to space, we’ll need research like this to better understand how to protect astronauts from the physical consequences. As Dr. Jamieson said in a UCSD press release: “This is essential knowledge as we enter a new era of commercial space travel and research in low Earth orbit.”