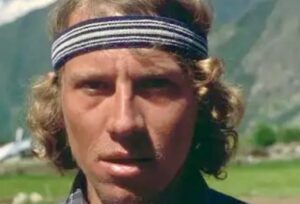

Steve McClure hunts joy on terrifying climbs.

From GreatNess to Lexicon and beyond, the Brit has made spine-tinglingly dangerous, very hard climbs his department. He’s famously taken 20-meter whippers, and less famously taken a 25m groundfall (very early in his career).

McClure seems to thrive in the liminal area between benchmark ascents and nauseating falls. Despite the risk assumed, he’s rarely been injured.

And here’s the thing: If you ask him, he doesn’t want the margin to be any wider.

Sound like a fine line to walk? Well, McClure’s dancing on it, while spinning plates with one hand and juggling torches with the other. When I interviewed him this week, he once referred to his gear placement style as “getting away with it.”

“I just really like the battle — the battle where it could go either way. And the closer I get to that, the better buzz I get out of it,” he explained. I’ve noticed that on most of my ascents, I find myself tying in at the bottom, thinking, ‘You know what? I’m going to go for this, it’s going to be flipping close, but it’s going to be such a ride. And I’m going to take it.'”

McClure’s most recent performance — on Le Voyage, James Pearson’s strikingly beautiful and highly popular trad line in Annot, France — was a nail-biter (as confirmed by his belayer). The route strings together sometimes sparse features up 40 meters of always-overhanging sandstone at E10 7a.

Confident, technically-sound gear placement is integral for any climber who leads Le Voyage. Consistently physical climbing, a pronounced 8a crux with tiny holds, and mandatory runouts up to several meters mean small gear must go in seamlessly and securely.

For these reasons, most climbers rehearse the route tirelessly before jumping on the sharp end. (McClure’s ascent is the seventh in its fairly young history — the recipe for success is well-known.)

But high-percentage outcomes are not what Steve McClure is seeking in climbing.

Getting the “buzz” he wants requires engaging with trad climbing on a psychological level. Uniquely to trad, you cannot do harder routes without accepting higher risk. Sparser features generally make placements more challenging and critical. More strenuous moves and sequences rob the climber of precious time to fiddle with gear.

At a certain difficulty, trad climbing forces a problematic calculation: How much of your safety are you willing to risk to get to the top?

View this post on Instagram

“As a trad climber, you try to weigh the level of risk. Maybe skipping a piece will give you the edge you need for success — especially if it’s fiddly and awkward to place. But then you increase the risk,” he explained.

On the other hand, McClure added, “You might decide that the risk [of skipping the piece] is not going to be too high. But it might psychologically crush you. The key to it is, do you really need it? If you skip it, can you get away with it?”

McClure’s sketch of the gear on Le Voyage spoke to that predicament. The business gets underway about halfway up. Consistent cracks give way to big reaches across blank rock. The area that protects the low-percentage crux will only accept tiny gear like stoppers better suited for aid climbing.

“If you place all the gear, you’d almost certainly be alright — almost certainly, but not completely,” McClure told me, with what I have to imagine was a wry smile. “If you opted to miss a few out — because it is proper [hard] to place — gosh, you’d be quite gripped.”

Steady hand

However, McClure said, he never once felt unsafe on Le Voyage.

It’s hard to overstate the difficulty of feeling comfortable on such a route. It has frayed the nerves of the likes of Babsi Zangerl, Siebe Vanhee, and Jacopo Larcher. A world-class climber can spend weeks working their way up to their first lead attempt.

In that vein, McClure’s relative lack of preparation also bears mentioning. By the time of the send, he had completed the crux move on top rope exactly once. During one ill-planned evening visit (of only a few total rehearsals), it got too dark for McClure to see the holds by the time he made it halfway up, so he cashed in the session.

A rest day was supposed to take place before he would launch into the redpoint. But according to his belayer, Patch Hammond, McClure got “bored” and provoked a trip to a casual multi-pitch climb nearby. The 6a climb the two had expected would have been one thing — but the climb turned out to be an 8a.

“It was not a rest day,” Hammond asserted.

McClure has deep experience and physical acuity, sure — but where did his pronounced edge in confidence come from? He generously attributed it to the person most vital to any trad climber: his belayer.

Hammond has logged vertical mileage with the likes of Leo Houlding. He’s climbed sandstone in the Czech Republic, where the ethic dictates using nothing but knotted ropes as gear. He’s been a frequent companion of McClure’s, and he belayed him on Le Voyage.

Hammond gave a detailed play-by-play of the send, which colors in the razor-thin margin by which McClure succeeded. McClure himself said, “I’ve been pretty close to a fail lots of times, and this was the closest. I absolutely dragged something out of nowhere.”

McClure gets away with it again

“I don’t know if this is psychology on his behalf, or some kind of mind game he plays,” Hammond began. But on the day McClure wound up sending Le Voyage, “he said, ‘Oh, I’m just going to go up and have a look.’”

With Pearson and his wife Caroline Ciavaldini standing by, it all started pretty innocently. McClure’s stated plan was to work the route in sections, familiarize himself with the gear, and work the cruxes after hanging on pieces he’d placed. —

“So he sort of sets off,” Hammond said, “looking not really warmed up and sort of scrapping around. He gets to the first rest and hangs out there. And then he started forgetting the sequences, and I’m shouting up at him, ‘No, Steve, go left there, go right there,’ all this sort of stuff.

“It didn’t feel like someone trying to climb an E10,” he said. “There was all this little, make it up as you go along type stuff.”

Playing make-believe or not, McClure soon found himself at the crux — looking “a little bit tired but not too bad,” Hammond recalled.

McClure reached for the first hold in the crux, a desperate crimp, and latched it.

Then, for some reason, he stopped.

“He sees a little wire placement, and he gets a tiny wire off his harness and puts it in, and clips it. And Caroline looks at me and is like, ‘That crimp is so small. You do not place gear there — you’re in the middle of the crux! You’re meant to be pushing on, not just hanging out!’”

“We’re all on the ground and we’re like, ‘Is this guy for real?’” Hammond said, laughing.

But McClure continued to wow his audience. Fighting for moves through huge fall potential, his feet flying wildly off the wall, he barely clung on as Hammond and the Pearsons cheered.

“It looked like he was in real trouble,” Hammond said.

Still, he made it to the exit crack. A segment of 7b climbing on rattly fingers was all that guarded the chains. McClure shook out briefly on the jug below, then quested up — and, to Hammond’s dismay, promptly back down.

“He started reversing it and I was like, oh no, he’s pumped out,” Hammond recalled. “But then he got back to the jug, shook out a little — and then he just motored up the top crack like it was nothing. And the route was done.”

“I was a bit speechless, actually, afterward. He’d really struggled on the top rope, he really didn’t look good, he didn’t have a proper sequence for the crux. And luckily James was there. He was like, ‘I can’t believe what I’ve just seen.’”

Proof of Hammond’s innate skill with rope in hand bore itself out in McClure’s send (and stated sense of comfort).

“For me, it’s about deciding what I’m going to do before I leave the ground, being happy with that decision, and then just going for it,” McClure said. “In terms of belayer trust, the most important thing is that when you leave the ground, you don’t think for a second what the belayer’s doing. Like, it must never enter your head. I one hundred percent trusted Patch.”

At the end of the day, McClure describes himself as rational. If a move demands death risk, he says, “It’s got to be a pretty easy one!” for him to accept it. Driven to hunt experiences rather than checklists of climbs completed, he’s concerned with the memories he’ll walk away with.

The top of the route is not the end-all, be-all target — the gambit between getting there and plummeting through space is.

“I’ve done a few routes where I’ve only just [sent] it. And they stick in my memory so strongly. And I know they’re sticking there because of that. There’s nothing worse than that feeling of, ‘Oh, that wasn’t even that hard.’

“I don’t get that very often, funny enough,” he quipped. “It’s pretty rare.”

Sure is.