My father always insisted on swimming in mountain tarns even in the depths of winter, which we all assumed meant there was something wrong with him. But health influencers have long touted the benefits of cold water plunges. The practice has been recommended for exercise recovery, increased energy levels, and even mental health disorders.

Curious about what cold plunges actually do to the human body, researchers at the University of Ottawa decided to take a closer look. The study reveals that after only a week of regular plunges, their subjects were seeing positive changes on a cellular level.

Cold plunges like this one in Iceland promise ‘rejuvination,’ and other vague but enticing health benefits. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

New evidence for an old practice

Humans seem to have an instinctual belief that getting really cold for a bit is good for us. Hippocrates recommended immersion in cold water for tetanus patients, and both the Roman physician Galen and Chinese surgeon Hua To favored an icy dip to treat fever.

In more modern times, the use of icy plunges expanded to all manner of ailments. English physician John Floyer published a treatise on temperature therapy in 1697. In it, he wrote that during summertime, “it is necessary to concente [sic] our Strength and Spirits by Cold bathing.” By following his own regimen, he claimed to have made himself healthier and heartier.

During the 19th century, physicians used cold therapy to treat mental illness, numb limbs for amputation (this was before actual anesthesia), and lower fevers. The upper classes started cold bathing for all manner of aches and for that ephemeral and still sought-after “wellness.”

Sea bathing became enormously popular as a general health and hygiene practice. One proponent was William Cullen, an 18th-century Scottish physician who prescribed cold showers (and cold enemas) for a range of ailments. The second thing did not catch on as much.

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, the popularity of cold water plunges has only increased. Sports medicine, especially, has embraced the practice for post-exercise and injury recovery. But just what exactly happens to a person when they undergo regular cold water treatment?

While it eventually became a popular recreation for all, sea-bathing in 18th and 19th-century England began as a health treatment. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Cellular change

The Ottawa researchers, led by Glen Kenny and Kelli King, submerged their subjects in 14°C (57˚F) water for an hour a day, seven days in a row. By collecting blood samples before, during, and after this regimen, they could watch the effects of the plunges.

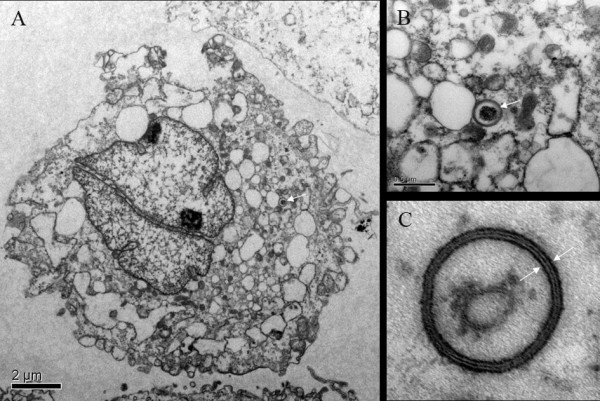

At first, it didn’t look good. The stress on the body was significant, and it threw off the autophagic systems of the cells. Autophagy is the cell’s cleanup and recycling system. When organelles are damaged or no longer needed, autophagic processes dispose of them. The material is then reused to make new cell parts. When this system isn’t working well, damaged or unbalanced cells build up. This buildup of damaged cells is part of the aging process.

If cells are damaged, the body may trigger apoptosis, which destroys a cell entirely. Apoptosis is normal, and some cells simply need to go. However, it’s much more efficient to repair them through autophagy rather than relying only on apoptosis. As the subjects’ autophagy went down, apoptosis went up to compensate.

But after a few days, the patients’ cells started to acclimate. Autophagy picked back up, though stress was still evident as well. By day four, the subjects were “over the hump,” as it were. Their cells were undergoing autophagy more and apoptosis less.

Autophagy in rat cells, observed through an electron microscope. Photo: Shen et al, via ResearchGate

Cold plunges for all?

The results are promising. By acclimating themselves to the cold, the subjects were better able to withstand the temperature extremes they were exposed to. More than that, Kelli King called cold water plunging a “tune-up for your body’s microscopic machinery.” The positive impact on autophagy has implications for disease prevention and the slowing of aging.

But this was a small study. There were only 10 subjects, all healthy adult men. People of different ages and sexes handle cold differently. For people with preexisting conditions, this sort of treatment can be dangerous.

One influential cold-water health guru, a Dutch man named Wim Hof, has faced multiple accusations of negligence for his recommendations. A Sunday Times investigation in May of 2023 revealed 11 deaths connected with his teachings, which combine ice water plunges and breathing exercises.

The American Heart Association has come out against cold therapy. Sudden exposure to extreme cold can trigger heart attacks even in young, fit people. In fact, University of Portsmouth researcher Mike Tipton, an expert in the physical effects of cold water, found young and healthy people had up to a three percent chance of cardiac arrhythmia in an icy plunge.

The University of Ottawa subjects were carefully monitored and vetted. The amateur fitness enthusiasts trying cold plunges at home are not. So take this study as it is: fascinating preliminary research. Not a how-to guide for a frigid DIY fountain of youth.

Promoting autophagy. A visitor takes a dip in the Northwest Passage. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko