Like many children, I was devoted to dinosaurs. Their grand scale, their strangeness, the sudden tragedy of their violent end, captures the imagination like little else. It’s strange for us, today, to remember than for much of our history, these ancient beasts were unknown.

Of course, we’ve been finding their bones around the world for probably as long as we’ve had eyes. They may have inspired mythological creatures like giants, dragons, and griffins. But it was only in the mid-19th century that we began to think of them as a specific group of long-extinct animals, and only in 1842 that they were given a name.

Less than a decade after the word dinosaur was coined, a sculptor with a keen interest in natural history was commissioned to create life-size models of prehistoric beasts. His creations fascinated and frightened, entering the public imagination with a grand dinner hosting the celebrity scientists of the day. On the last night of 1853, twenty-one prominent paleontologists ate an eight-course meal inside a massive model of an iguanodon.

Artist John Martin painted these enchantingly big-eyed creatures in 1837, inspired by the very first fossilized iguanodon bones. They don’t look a lot like iguanodons, but they sure have charmed me.

We should get some beasts in this park

In 1851, the Great Exhibition brought over six million visitors to Hyde Park in London, where a specially built Crystal Palace held all the wonders of the Victorian era. But after that first World’s Fair ended, Britain was left with a big glass building just sort of sitting there. In 1852, the Crystal Palace was disassembled and rebuilt on Sydenham Hill, southeast of London.

There, artists and experts gathered to design and build exhibitions on a massive scale. Different courts showcased the history of art, society, and the natural world. All aspects of the park were designed around what Victorian elites considered the proper order of things. Science and history were enlisted to support the modern British imperial project.

A scion of that project, Prince Albert, first suggested an area dedicated to all those strange prehistoric beasts that people had been digging up over the past few years. What were they calling them again…? Ah, yes. Antediluvian Monsters.

The man they found for the job was Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, a sculptor and artist who had illustrated scientific works, including The Zoology of the Voyage of HMS Beagle. Renowned gardener Joseph Paxton designed a “primordial” landscape with a series of islands, which would be populated by full-sized statuary recreations of extinct animals.

The iguanodon, still in its cast, alongside the other dinosaurs still in progress at Waterhouse’s workshop. Photo: Illustrated London News Archive

Designing dinosaurs

While Hawkins himself was educated and interested in natural history, the primary scientific mind behind the project was paleontologist Richard Owen: the man who first called them dinosaurs.

In the early 19th century, a few very important fossils were unearthed and described scientifically for the first time. Geologist William Buckland presented Megalosaurus in 1824, and amateur paleontologist husband-wife duo Gideon and Mary Ann Mantell discovered the Hylaeosaurus and Iguanodon in the same decade.

In 1842, Owen compared these three extinct animals and theorized, based on shared anatomy, that they were all part of the same Mesozoic family. He called this family Dinosauria, a Greek construct meaning “fearfully great lizard”.

A decade later, Owen brought all his expertise to bear on the Crystal Park dinosaurs project. (A brief note on terms: Technically, only four of the statues are what we now define as dinosaurs, but I’m going to keep referring to them all that way for the sake of brevity.)

Hawkins and Owen were the first to create 3D, full-size speculative replicas of extinct animals. Hawkins created endless sketches and miniature models, studying the fossils and the literature, trying to get it right. Their reconstructions also drew inspiration from modern animals. This is where things got a bit contentious.

One of the iguanodon teeth that Mary Ann Mantell found on a Sussex beach. Photo: London Natural History Museum

A tale of two iguanodons

The biggest debate revolved around the iguanodon. You can tell a lot from bones, but there’s also a lot you can’t tell. The biggest contention revolved around how they stood and moved.

The first camp was headed by Gideon Mantell, who, as the name he gave it suggests, believed the iguanodon had a lizard-like build. His model had longer hind limbs than forelimbs (this later proved correct) and a long, whip-like tail (not correct, but cool).

Owen was on the other side, vocally championing his view that the iguanodon and the other dinosaurs were built more like large mammals. His iguanodon has the broad-shouldered stance of a rhinoceros and a horn to match.

Owen, a seemingly rather difficult and pugilistic personality, attacked Mantell, publicly accusing him of plagiarizing Owen’s own work and calling him “nothing more than a collector of fossils,” who could only provide materials for real scientists like himself.

Mantell, unfortunately, was dealing with chronic pain and an attendant opiate addiction following a carriage accident, and his decline prevented a vigorous defence. He died of an overdose in 1852. A postmortem examination found the twisted spine behind his years of pain. Owen added Mantell’s spine to his collection in the Hunterian Museum.

The iguanodon based on Owen’s theory stands behind. Mantell’s lizard-like iguanodon lies in front. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A fearfully great dinner

Hawkins, perhaps wanting to balance the two conflicting interpretations, ended up creating two iguanodons. One was reptilian, the other was mammalian in build. But the compromise only went so far. When it came time for the big dinner, it was Owen’s iguanodon that would be the star.

That big dinner was an event that Hawkins hoped would legitimize the scientific accuracy of his designs and get people excited for their upcoming unveiling. To that end, he sent out dozens of invitations to prominent zoologists, geologists, paleontologists, and anatomists. While he was at it, he also invited the press and the wealthy magnates who had sponsored the building of the park.

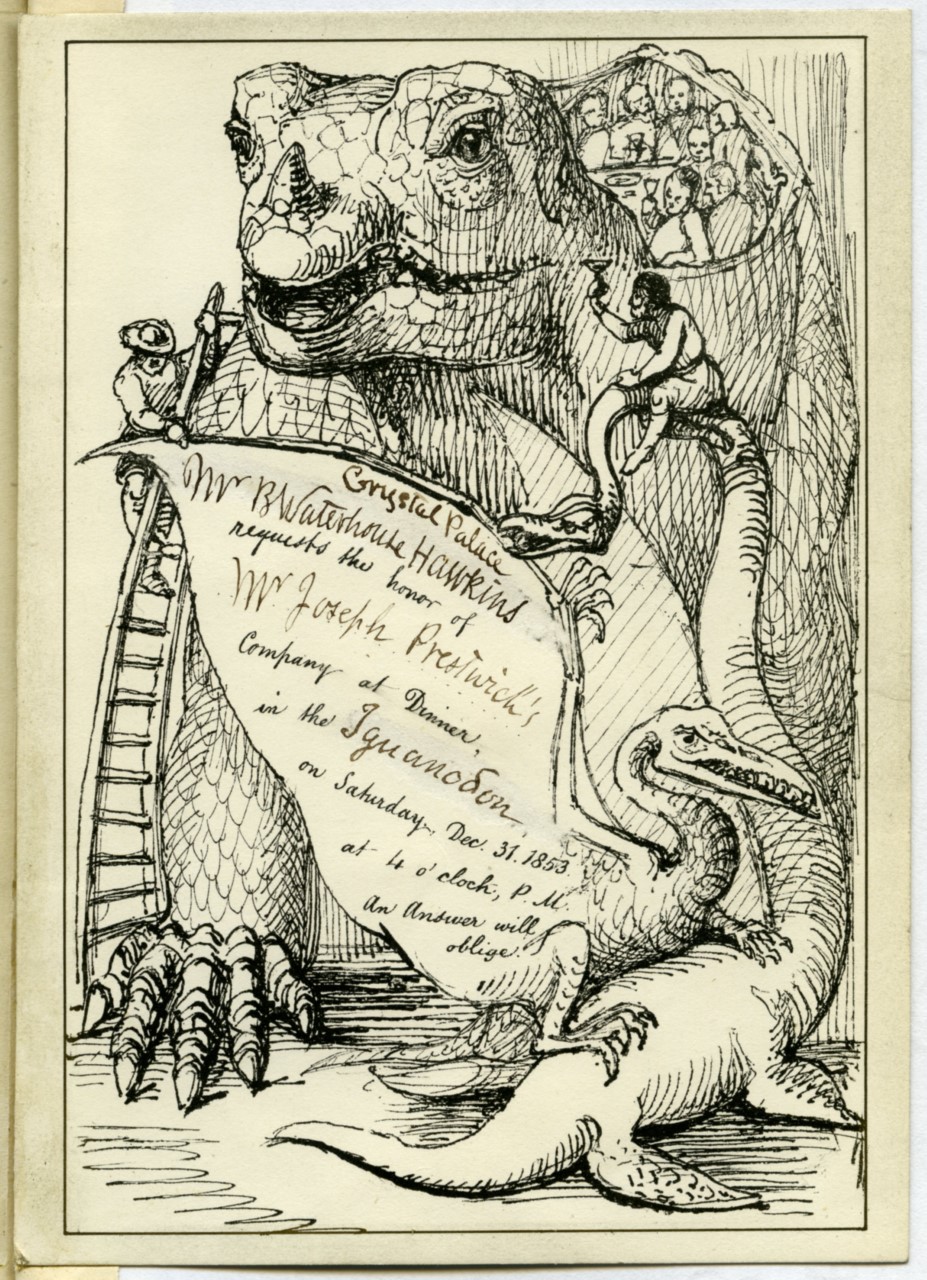

These luminaries received a card, illustrated by Hawkins with prehistoric creatures, inviting them to dinner “in the Iguanodon” on New Year’s Eve. Twenty-one of them turned up, probably not knowing what to expect.

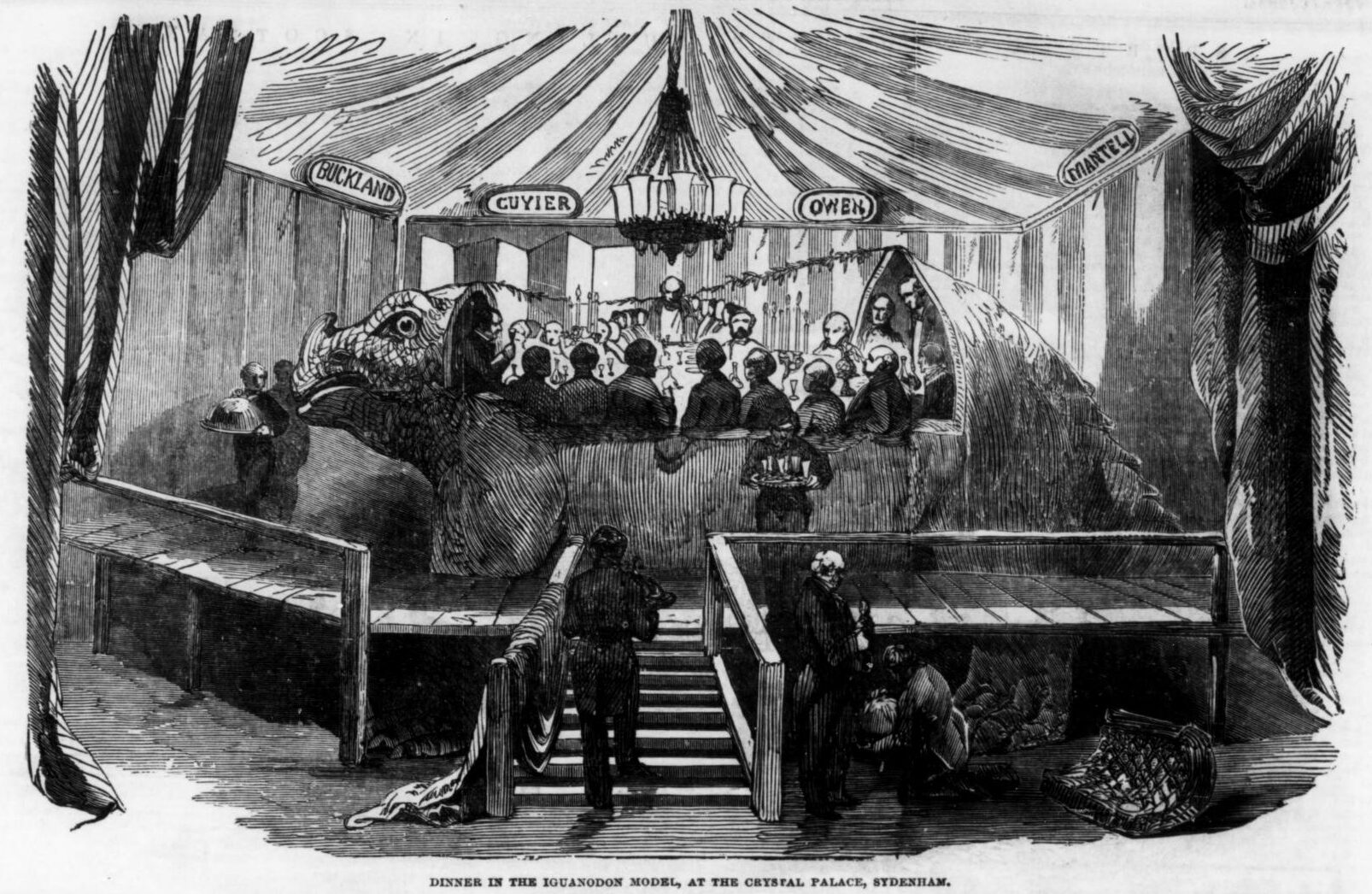

What they found was the massive iguanodon, hollowed out with an open back, on a stage hung with banners bearing the names of famous deceased zoologists, and Owens. Owens himself sat at the head, as the symbolically powerful brain of the whole affair.

He opened the event as the main speaker, praising the models in progress and their accuracy. He finished by offering a toast to the deceased Mantell. Though he’d refused to admit it when Mantell lived, Owen was now willing to drink to him as the “discoverer of the iguanodon.”

Generously, one could interpret this as a burying of the hatchet. But considering the time and exact place, it may have been more like a victory lap.

The invitation sent to Joseph Prestwich, geologist. Photo: Geological Society Archives

The jolly old beast

After a moment of silence for Mantell, the mood picked up. Attendants, including naturalist Edward Forbes, geologist Joseph Prestwich, ornithologist John Gould, and the managing director of the Crystal Palace, grew merry.

Forbes had written a song for the occasion and hired a singer to perform it. The original music is lost, but we still have the lyrics. The chorus goes: “The jolly old beast/Is not deceased/There’s life in him again!/ROAR!”

From surviving menu cards, we know diners enjoyed an eight-course meal that included dishes like mock turtle soup, turbot à l’hollandaise, pigeon pie, and salmi de perdrix. Their desserts were macedoine or orange jellies, Bavarian cream, Charlotte Russe cake, and nougat à la Chantilly. All of it was washed down liberally with sherry, madeira, port, moselle, and claret.

Things kicked off at 4 pm, but it was well into 1854 before the distinguished guests wrapped up, stumbling to the train line.

Hawkins sent this sketch of the dinner to the press. Photo: Illustrative London News Archive

In all the papers

The dinner was widely publicized. Lengthy reports appeared in the most popular papers and magazines like Punch and the Illustrated London News (ILN). The reports have more than a touch of humor, with Punch joking that “if it had been an earlier geological period, they might perhaps have occupied the Iguanodon’s inside without having any dinner there.”

Alongside a massive illustration, ILN produced a long and effusive column of text. On the same page, ILN included a long article about Owen’s work with other extinct animals. The story appeared in over a hundred newspapers across the British Isles. For many, it was the first introduction to dinosaurs and the science of paleontology.

When the statues their newspapers had praised so highly were finally unveiled, crowds flocked to the new Crystal Palace park to see the massive ancient beasts which had once prowled their island. They proved so popular that Hawkins made a bustling side income selling miniature models and was commissioned to make many more extinct animal models for the park.

The impact of these massive, life-size models on the public imagination was electric. This was a public that hadn’t even been introduced to the concept of evolution yet, and it was now coming face to face with massive, draconic beasts existing on a timescale hard even to comprehend. Dinosaur parks proliferated in the following decades.

Soon they began appearing in popular works by Jules Verne, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Charles Dickens. The second age of the dinosaurs had begun. God willing and the creek don’t rise, it’ll never end.

This print by contemporary artist George Baxter shows the way the statues were first displayed. Photo: The Wellcome Collection

The Crystal Park dinosaurs reign eternal

The Crystal Palace burned down in 1936. But the park remains, including the 30-odd statues. Over the many years out in the elements, by 2014 the old beasts had taken quite a beating. Several were missing outright.

A charitable organization, formed to protect and maintain the statues and the surrounding geological landscape and art, stepped in. Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs successfully campaigned for funding, and the statues were subject to a year’s long conservation program. The dinosaurs were repaired, repainted and in the case of a stolen Palaeotherium, replaced. Historic England ensured the statues’ digital preservation in 2023 with the creation of digital scans.

Conservation work is ongoing, and the iguanodons will continue to stand as they grow more and more out of date. Modern paleontological work has shown that real iguanodons looked absolutely nothing like the statues. Oh well.