It was a scene out of a horror movie. There was no sound, the air was deadly still, and the putrid smell of rotting eggs wouldn’t go away. Bodies of people and animals lay motionless in several villages near Lake Nyos. In August 1986, hundreds of people died suddenly in one of the rarest geological events of the modern era.

Background

Lake Nyos is a 1.9km long and 200m deep crater lake located in northwestern Cameroon. Between 9 pm and 10 pm on Aug. 21, 1986, villagers in the valley heard a strange rumbling noise. Those closest to the lake itself described a bubbling noise. Then, white smoke started to emerge from the lake and travel northwards. Then, people and animals suddenly dropped dead, killed by a silent assailant. The cloud is called a mazuku, a deadly blanket of carbon dioxide.

Around 1,800 people died, all living in the affected towns of Nyos, Cha, Fang, Mashi, and Subum. Most residents were farmers. About 3,500 livestock also perished. Insects stopped making sounds. It was as if time stood still. The lake water was usually a brilliant blue color, but after the eruption, it turned reddish-brown.

A rescue team did not arrive until 36 hours later. Assisted by the Cameroon military, everyone had to wear protective gear and oxygen tanks. Sadly, the dead could not receive individual funerals, so mass graves were dug.

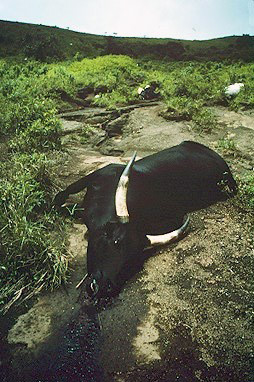

A dead cow from the Lake Nyos disaster. Photo: Jack Lockwood/USGS

The aftermath and effects varied. The survivors (four in Nyos and around 5,000 in the general area) were all in comas that ranged from six to 36 hours. They reported falling unconscious and waking up dazed. They escaped death because they lived on higher ground.

Some had respiratory issues, which cleared up soon after. Women suffered miscarriages; others had pneumonia. Some committed suicide after seeing the horror or losing family members. Pictures of the dead bodies also contained big lesions caused by low levels of oxygen.

Limnic eruption

The disaster at Lake Nyos is an example of a limnic eruption, also called a gas eruption. It happens when a lake, typically a volcanic crater lake, instantaneously releases a large amount of dissolved gases.

In this case, Lake Nyos primarily contained carbon dioxide with traces of sulfur dioxide. This gas release can occur when pressure builds up at the lake’s bottom from geothermal activity.

When the pressure becomes too great, gas rapidly escapes to the surface and forms a dense, toxic cloud. The cloud can blanket the ground, displacing oxygen and asphyxiating people and animals. It does not seem to affect plant life.

Lake Kivu has the potential for a devastating limnic eruption. Photo: ondraphototravel/Shutterstock

Two other dangerous lakes

Lake Nyos is not the only incident. Just 100km away, Lake Monoun erupted on Aug. 15, 1984, killing 37 people. Lake Nyos erupted almost exactly two years later.

Lake Nyos and Lake Monoun are two of three lakes in Africa that experience these types of eruptions. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the third lake, Lake Kivu, expels not just carbon dioxide but also methane and hydrogen sulfide. Though it has not erupted catastrophically like the other two, scientists worry that it has the potential to release over 300 cubic kilometers of carbon dioxide and 60 cubic kilometers of methane, according to journalist Nicola Jones of Nature.

Though companies commercially extract methane from the lake, volcanic activity can trigger a limnic eruption at any time. In 2021, there was a scare when Mount Nyiragongo erupted and triggered small amounts of gas to emerge from the lake. A volcanic crater lake in Italy called Lake Albano also has the potential to have a limnic eruption.

In Russia, the Valley of Geysers is located in the super-active Kamchatka region. Locals refer to an adjacent low-lying area as the Valley of Death because heavier-than-air carbon dioxide can blanket the ground and kill wildlife. While the Valley of the Geysers is a tourist spot (it’s the second-largest geyser field on Earth, after Yellowstone), the nearby Valley of Death is understandably off-limits.

The Valley of the Geysers, top, and the Valley of Death, below, in Kamchatka, Russia. Both: Jerry Kobalenko

How it happened

“Anaesthetic concentrations of carbon dioxide [was] formed as the gas mixed with air during its flow into the valleys,” explained the official study written by Peter J. Baxter et al.

Furthermore, on this calm night, the gas collected in hollows and would stay there until the winds or solar heat dispersed it. Although the initial cloud that erupted from the lake was an estimated 50-100m thick, it is unclear how thick the blanket that settled upon the villages was.

But why are these lakes concentrated in one region? Lake Nyos is not a very old lake, possibly just a few hundred years old. Lake Nyos and Lake Monoun are in the Oku Volcanic Field, part of a 1,600km-long chain of volcanoes that runs from Nigeria and Cameroon in the mainland to the southernmost island of Annobón.

Lake Kivu lies in the East Africa Rift Valley, which is notorious for its highly active and dangerous volcanic formations. The region’s volcanism is due to the split between the African and South American plates over 100 million years ago.

Thirty-seven people died in the first limnic eruption, at Lake Monoun above. Photo: Prosper Mekem/Wikipedia Commons

A bubble of CO2

According to NASA, Lake Nyos sits on the edge of an inactive volcano and a pocket of magma. “Carbon dioxide from that magma slowly percolates through Earth’s crust with the groundwater and accumulates in the bottom of the lake,” states NASA. “Eventually, the gas becomes too concentrated, and a bubble of CO2 bursts from the lake.”

What triggered the eruption? Most likely a landslide or a small earthquake. This would have released carbon dioxide, which accumulated to over 10%.

So why carbon dioxide? Why wasn’t it mixed with the usual volcanic gases — sulfur dioxide, hydrogen fluoride, hydrogen sulfide, hydrogen chloride, and carbon monoxide? While water tests showed that the accumulated gas was almost completely carbon dioxide, the rotten egg or gunpowder smell after the eruption suggests that very small amounts of sulfur dioxide might have been present. However, when carbon dioxide is saturated in water, it also gives off this unpleasant smell.

Prevention

To prevent a recurrence, measures were implemented to manage the buildup in Lake Nyos. At first, scientists considered blowing up the lake with a bomb. Instead, they opted for a gradual degassing of the lake.

In 2001, French engineers installed degassing pipes to release the trapped gases in a controlled manner. A plastic tube reached 203m down and conducted the gas safely into the atmosphere. Authorities installed two more pipes in 2011. They did not want to take any chances with Lake Monoun, so they installed three pipes there as well.

They also relocated several communities and have tried to discourage those who wish to return to the lake decades later. Apparently, the lake is still toxic. However, residents claim that this is their ancestral land, and they prefer to bear the risk.