Today is the 70th anniversary of the first ascent of 8,586m Kangchenjunga, the world’s third-highest mountain.

Located on the border of Nepal and Sikkim, India, Kangchenjunga means the Five Treasures of the Great Snow, referencing its five prominent peaks and cultural significance in Sikkim, where it is considered sacred. Kangchenjunga drew early mountaineers because of its height and extreme technical challenges. Before its first ascent in 1955, 13 expeditions targeted the peak.

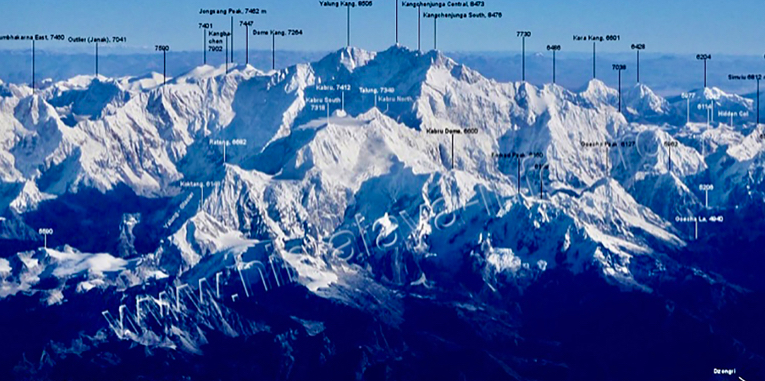

The Kangchenjunga Massif from the southwest. Photo: Gunter Seyfferth

Early exploration and reconnaissance

The climbing history of Kangchenjunga begins with exploration rather than summit bids. In 1899, British mountaineer Douglas Freshfield became the first European to circumnavigate the mountain, mapping its glaciers and ridges. Freshfield described the Northwest Face as a formidable barrier, seemingly designed to repel climbers with its ice and snow defenses. His observations laid the groundwork for future attempts, suggesting potential routes via the Southwest Face and the Kangchenjunga Glacier.

The first summit attempt

The first serious attempt to climb Kangchenjunga came in 1905, led by controversial British mountaineer and occultist Aleister Crowley, who later styled himself “the wickedest man in the world.” The expedition also included Jules Jacot-Guillarmod, Charles Reymond, and Alexis Pache of Switzerland, along with Alcesti C. Rigo de Righi (an Italian hotelier from Darjeeling), and four Sherpas.

The expedition approached from the Nepal side, targeting Kangchenjunga’s Southwest Face via the Yalung Glacier, a route suggested by Freshfield. Crowley, who had previously attempted K2 in 1902, led with a mixture of ambition and recklessness.

Kangchenjunga from Gangtok, Sikkim. Photo: Johannes Bahrdt

The team established Camp 7 at approximately 6,300m. However, the expedition unraveled because of Crowley’s leadership and dangerous conditions. On September 1, an avalanche struck and swept the climbers away, killing Pache and three Sherpas (The Himalayan Database does not list the names of the Sherpas.) De Righi was partially buried, and the survivors called for help. Crowley reportedly remained in his tent, later claiming the “Demon of Kangchenjunga” had been appeased by the deaths. Earlier in the expedition, one porter died in a fall.

The avalanche ended the 1905 attempt, and Crowley’s reputation suffered.

Kellas’ reconnaissance

Between 1907 and 1921, Scottish chemist and mountaineer Alexander Mitchell Kellas made six visits to the Kangchenjunga region, climbing in alpine style with Sherpa and Lepcha porters. Kellas, a pioneer of high-altitude physiology, believed peaks like Kangchenjunga could be climbed without supplemental oxygen.

In the spring of 1910, Kellas made a solo reconnaissance trip on the northeast side of Kangchenjunga and explored near Kirat Chuli. Kellas studied the Zemu Gap, Simvu Saddle, and Kangchenjunga Glacier, making several first ascents of peaks over 6,000m, including 7,128m Pauhunri (1911) and 6,965m Langpo (1910).

Kellas’ work provided critical knowledge of the terrain and Sherpa capabilities, though he never attempted Kangchenjunga’s summit. Tragically, Kellas died in 1921 during an Everest reconnaissance expedition, but his contributions shaped Himalayan mountaineering.

From left to right, Jules Jacot-Guillarmod, Charles Adolphe Reymond, and Alcesti C. Rigo De Righi at Kangchenjunga Base Camp in 1905. Photo: Jules Jacot-Guillarmod

Interwar attempts

After Crowley’s failed attempt, Kangchenjunga saw no major expeditions until after World War I, when mountaineering interest in the Himalaya surged. In the autumn of 1920, British climber Harold Raeburn, accompanied by Ferdie Crawford, scouted the southwest side of Kangchenjunga and reached 6,400m.

Solo attempt and death

Edgar Francis Farmer was a young man from the Standard Oil Company of New York who dreamed of climbing Kangchenjunga. In May 1929, he set out on a solo attempt to reach the summit by the Southwest Face. The decision led to his death.

Thanks to detailed reporting in The Himalayan Journal and the American Alpine Journal, Farmer’s climb was well covered. Farmer wasn’t an experienced Himalayan climber; his only mountaineering background was in the Rockies. Still, he was determined and had studied climbing books. He kept his ambitious plan secret, not sharing it with officials or experienced climbers in Darjeeling who might have warned him against it.

Farmer set out on May 6, with skilled Sherpa and Bhutia porters, claiming he would explore the Guicha La region. Farmer led his team across the Kang La into Nepal, and camped on the Yalung Glacier near Kangchenjunga’s Southwest Face. On May 26, with three porters, he tackled the icefall toward the Talung Saddle. Though personally well-equipped, his porters lacked proper gear.

With melting snow making the climb risky, the head porter, Lobsang, urged Farmer to turn back. However, the American, promising to stop by noon, continued alone into the mist despite the porters’ pleas.

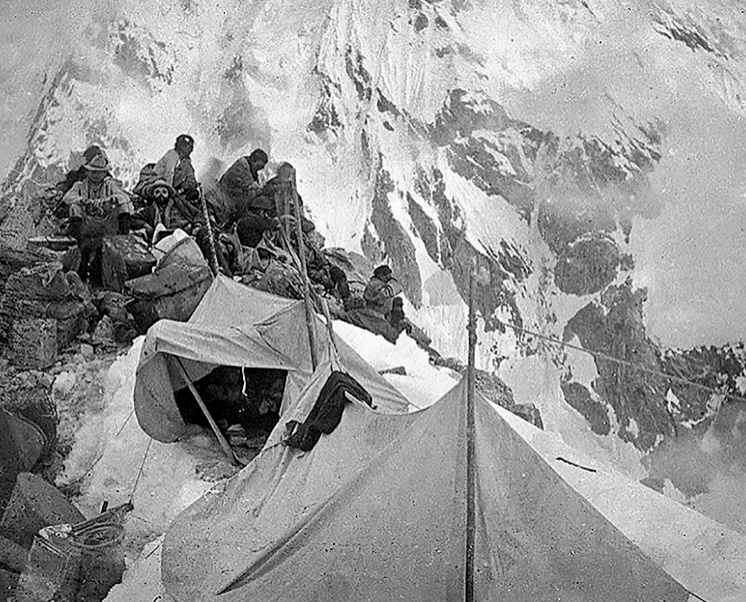

Camp 4 on Kangchenjunga in 1905. Photo: Cordada

By 5 pm, the porters saw Farmer climbing higher, but the mist soon hid him. The porters signaled by torch, hoping he would return. The next morning, they spotted Farmer up a steep slope, moving oddly, possibly snowblind. He then vanished at approximately 6,000m.

Out of food, the porters waited until May 28 before descending. On May 30, they reached Tseram, traded a coat for food, and sent a porter to Darjeeling. The porter reported the tragedy on June 6.

Farmer had arrived in Darjeeling earlier that year and met G.H. Wood-Johnson, an experienced Himalayan climber. Wood-Johnson helped Farmer hire skilled porters, including Lobsang, a veteran of Everest expeditions. Lobsang’s detailed account to the Indian Police matched the porters’ story, describing how Farmer misled them about his real plans.

Farmer’s obsession with reaching the summit of Kangchenjunga clouded his judgment.

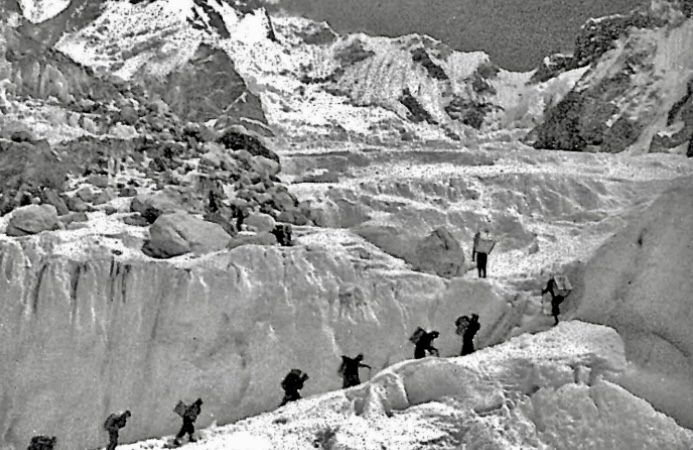

Porters on the Northeast Spur between Camps 7 and 8, during the 1929 German expedition. Photo: Alpine Journal

German attempt

In the summer of 1929, German climber Paul Bauer led a well-organized German-Austrian-British expedition targeting the Northeast Spur from the Sikkim side. Bauer’s team first made a reconnaissance of the East-Southeast Ridge, but then focused on the Northeast Spur-North Ridge route. The party reached 7,400m, where a five-day storm stopped them. The long and exposed Northeast Spur proved technically challenging and avalanche-prone, ultimately forcing a retreat.

In the spring of 1930, an international expedition led by Swiss mountaineer Gunter Oskar Dyhrenfurth attempted the Northwest Face via the Kangchenjunga Glacier from Nepal. The team, including German, British, Swiss, and Austrian climbers, aimed to follow Freshfield’s suggested route. They established Base Camp near Pangpema, but faced disaster when a massive ice avalanche killed Chettan Sherpa, one of their strongest high-altitude porters, and nearly wiped out the team. The expedition abandoned the climb at 6,400m, but completed a circuit of Kangchenjunga, ascending three lower peaks.

Years later, other climbers found Chettan Sherpa’s remains and G.O. Dyhrenfurth’s ice axe. According to a letter written by Dyhrenfurth’s son, Norman Dyhrenfurth, on November 27, 1987, and sent to The Himalayan Database, Chettan Sherpa was crushed by a huge ice avalanche on May 8, 1930. After more than an hour of artificial respiration, he was buried near Camp 2.

“My father’s old ice-axe was indeed placed on his grave. Perhaps a recent avalanche brought his remains to the surface and broke the ice axe as well. What a strong coincidence,” Norman Dyhrenfurth wrote.

Kangchenjunga’s Northeast Face and Spur in 1929. Photo: Alpine Journal

Bauer returned in 1931 with a large German team of 10 climbers. They followed the same Northeast Spur. Despite persistent bad weather, they reached 7,940m, but a dangerous snow slope between the Spur and the North Ridge proved impassable. The expedition suffered losses when climber Hermann Schaller and Sherpa Pasang died in a fall, and Sirdar Lobsang and porter Babu Lall succumbed to illness. Bauer’s determination earned respect, but Kangchenjunga remained unclimbed.

Further reconnaissance

George Frey of Switzerland and Gilmour C. Lewis of the UK made a reconnaissance from the southeast to the southwest side of Kangchenjunga in the autumn of 1951. This was followed by John Kempe’s (UK) reconnaissance in the spring of 1953, also with C. Lewis, of Kangchenjunga’s Southwest Face.

Kempe returned in the spring of 1954 with seven other climbers (two of them Sherpas), again scouting the Southwest Face.

All attempts and reconnaissance of Kangchenjunga between 1905 and 1954 were carried out without supplemental oxygen.

Charles Evans. Photo: Himalayan Club

The 1955 British Kangchenjunga Expedition

By the 1950s, Kangchenjunga had gained a fearsome reputation, with 11 people dead and no summits. After the successful first ascents of Everest (1953) and K2 (1954), Kangchenjunga became the highest unclimbed peak, drawing intense interest.

In 1955, a British expedition led by Charles Evans, deputy leader of the 1953 Everest expedition, achieved the first confirmed ascent. The team’s success was a mountaineering landmark, often considered a greater achievement than Everest because of Kangchenjunga’s technical difficulty and remoteness.

The Great Shelf on Kangchenjunga. 1955. Photo: Tony Streather Collection

The expedition included experienced mountaineers and Sherpas, carefully selected for their skills and Himalayan experience: Charles Evans (leader, 36, a seasoned Himalayan climber, calm and strategic, who negotiated access with Sikkim’s authorities), Norman Hardie (deputy leader, 30, a New Zealand engineer and expert ice climber, responsible for oxygen equipment), George Band (26, a Cambridge graduate and Everest 1953 veteran, in charge of food logistics), Joe Brown (24, a British working-class rock climbing prodigy with no prior Himalayan experience but exceptional technical skills), John Clegg (29, expedition doctor and alpine climber), John Jackson (34, a Himalayan veteran who had been on the 1954 Kangchenjunga reconnaissance), Tom McKinnon (42, expedition photographer with extensive Himalayan experience), John Neil Mather (28, an ice and snow specialist from the Alps), and Tony Streather (29, an army captain with broad mountaineering experience, including the 1953 K2 attempt, responsible for porters).

The team also included Dawa Tenzing, Sirdar, 45, a highly respected Sherpa leader, known as the King of the Sherpas for his stamina and character. Additional Sherpas included Ang Temba, Ang Noru, Tashi, Urkien, Ila Tenzing, and Pemi Dorje, who played critical roles carrying supplies and establishing camps.

Kangchenjunga Base Camp in 1955. Photo: Tony Streather

The route

The expedition, including over 300 porters and 26 climbing Sherpas, approached from Darjeeling, a 10-day trek along the Sikkim border and through Nepal to the Yalung Valley.

The team initially attempted a route reconnoitered by John Kempe in 1954 (Kempe’s Buttress) but found it impractical because of the very unstable lower icefall.

“We could find no safe route from the top of Kempe’s Buttress to the Plateau,” Evans noted in the American Alpine Journal.

Instead, they chose the Southwest Face via the Yalung Glacier, the same route attempted by Crowley in 1905. This route ascended snow and ice slopes west of the Western Buttress, crossing what they called The Hump to the upper icefall and reaching the Great Shelf, a large ice terrace at 7,300m. From there, it followed the Gangway, a snow slope leading to the summit ridge, avoiding the dangerous “Sickle” formation.

The 1955 first ascent route. Photo: Culturademontania

Kangchenjunga’s first ascent

The expedition began with Evans, Hardie, and two Sherpas reaching 7,150m, establishing Camp 4 and identifying the route to the Great Shelf. By May 13, the team reached the Great Shelf and established Camp 5 at 7,710m. This camp was under a vertical ice cliff, higher than any previous Kangchenjunga attempt.

George Band at the summit of Kangchenjunga. Photo: Royal Geographic Society and Alpine Club of Great Britain

On May 15, Jackson and McKinnon led Sherpa teams to stock Camp 5, battling deep snow and an avalanche that scattered supplies. Jackson suffered snow blindness, but continued, guided by Sherpas.

The team regrouped at Base Camp, where Evans announced the summit plan: Joe Brown and George Band would lead the first summit attempt, supported by Evans, Mather, Dawa Tenzing, Ang Temba, Ang Noru, and Tashi.

The Sherpa team from the 1955 Kangchenjunga expedition. Photo: Himalayan Club

Hardie, Streather, Urkien, and Ila Tenzing formed a second summit team and planned to follow a day behind. On May 24, they established Camp 6 at 8,200m on a precarious snow ledge. It was the final camp before the summit.

Crossing a crevasse in 1955. Photo: Himalayan Club

On May 25, Brown and Band set out from Camp 6 at 8,200m. They navigated the Gangway, facing soft snow and avalanche debris. Brown led a challenging six-meter rock climb up a crack with a slight overhang, rated very difficult at sea level but grueling at 8,500m.

On May 25 at 2:45 pm, Band and Brown topped out. Respecting Sikkim’s religious sensitivities and as Evans had promised the Sikkimese prime minister, they stopped just short of the true summit. Clouds obscured most of the view, but they glimpsed Makalu, Lhotse, and Everest 130km away. After an hour, they descended, discarding empty oxygen tanks and reaching Camp 6 as darkness fell. On May 26, at noon, Hardie and Streather also reached the summit.

In the upper icefall in 1955. Photo: Expeditions-unlimited

Supplemental oxygen was a key component in the expedition’s strategy, reflecting the growing acceptance of its necessity at extreme altitudes. The team used oxygen for climbing and sleeping above Camp 3 (6,700m). Sherpas used oxygen only for carries above Camp 5 (7,700m). George Band and Joe Brown carried 1,600 liters of oxygen each for their summit push, while Hardie and Streather carried 2,400 liters each. However, leaks reduced Hardie and Streather’s supply, forcing Streather to descend without oxygen. The oxygen systems posed challenges, including mask leaks that fogged goggles, contributing to Jackson’s snow blindness during a carry to Camp 5.

A snowstorm. Photo: Tony Streather Collection

Sherpa contributions

Sherpas were integral to the expedition’s success, carrying heavy loads, establishing camps, and breaking trail in deep snow. Dawa Tenzing, the sirdar, was praised for his leadership and stamina. He had also previously outperformed others on Everest in 1953.

Sherpas like Ang Temba, Ang Noru, and Tashi supported the summit teams, carrying vital supplies to Camp 6. However, the expedition was marred by the death of Pemi Dorje, Dawa Tenzing’s brother-in-law, who died of a stroke at Base Camp on May 26, after an exhausting carry to Camp 5.

George Band under the summit of Kangchenjunga in 1955. Photo: Expeditions-unlimited

The 1955 British expedition achieved the first ascent of Kangchenjunga through meticulous planning, skilled climbing, and Sherpa support, navigating the Southwest Face with supplemental oxygen. The climb was a historic success, proving that even the Demon of Kangchenjunga could be tamed through perseverance and respect for the mountain’s cultural significance.

The second ascent of Kangchenjunga did not occur until the spring of 1977, when Prem Chand Dogra and Nima Dorje Sherpa, members of the Indian Army Expedition led by Narinder Kumar, carried out the ascent via the East Spur-North Ridge route.

Subsequent ascents included a 1979 climb by Doug Scott, Pete Boardman, and Joe Tasker, who made the first Kangchenjunga ascent without oxygen or high-altitude porters, via a new route.

A photo of the 1990 reunion of the 1955 Kangchenjunga climbers. From left to right, front: Neil Mather, John Jackson, Charles Evans, and Joe Brown. Left to right, rear: Tony Streather, Norman Hardie, George Band, and John Clegg. Photo: Wikimedia