Seventy-five years ago, on June 3, 1950, French mountaineers Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal achieved what no climber had done before: summit an 8,000m peak. Herzog and Lachenal topped out on 8,091m Annapurna I, the 10th highest peak in the world, via the North Face and without supplemental oxygen.

In west-central Nepal, Annapurna I is the highest peak in the Annapurna massif. The name Annapurna originates from Sanskrit, combining “Anna” (meaning food or grain) and “Purna” (meaning full or abundant). It translates to “the giver of food,” or “she who is full of food.” In Hindu mythology, Annapurna is a goddess of nourishment and abundance, an incarnation of Parvati, Shiva’s consort, revered for sustaining life.

There are no registered attempts to climb Annapurna I before 1950. Its first ascent was not just a climb, but a race against time, weather, and human limits, marked by unparalleled courage and harrowing consequences.

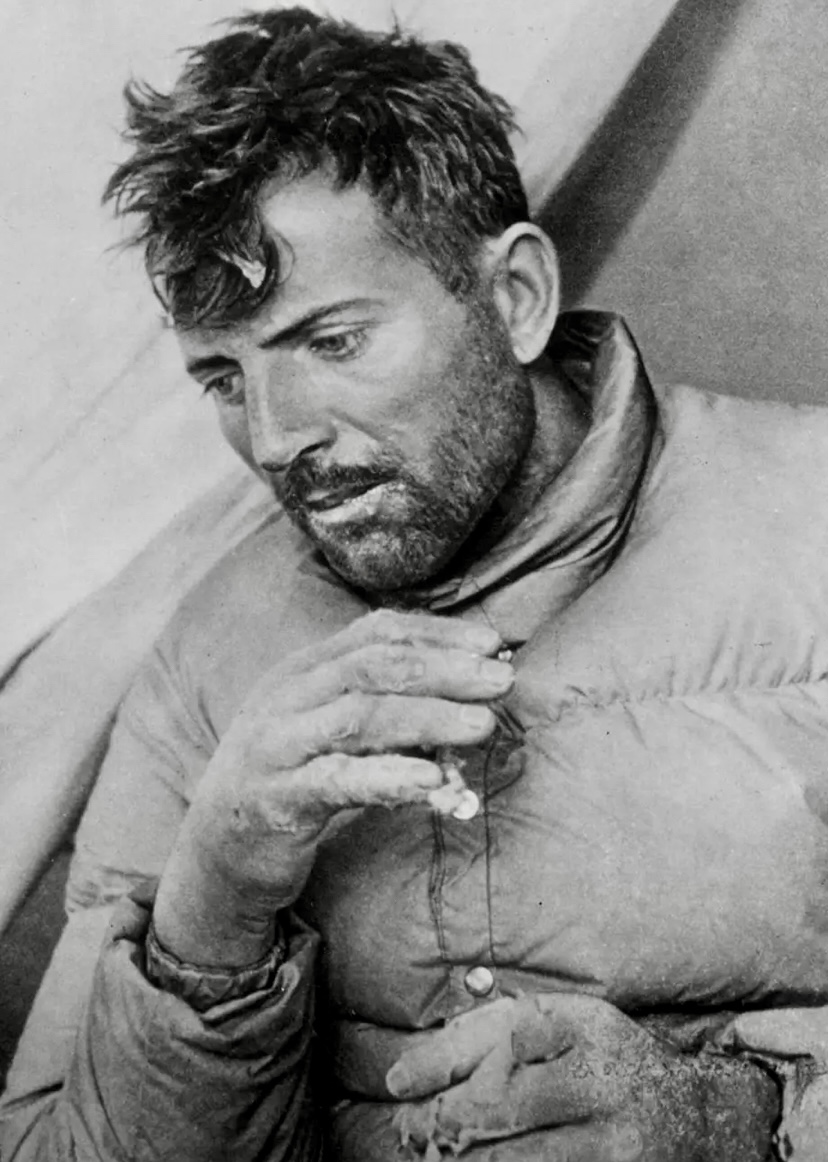

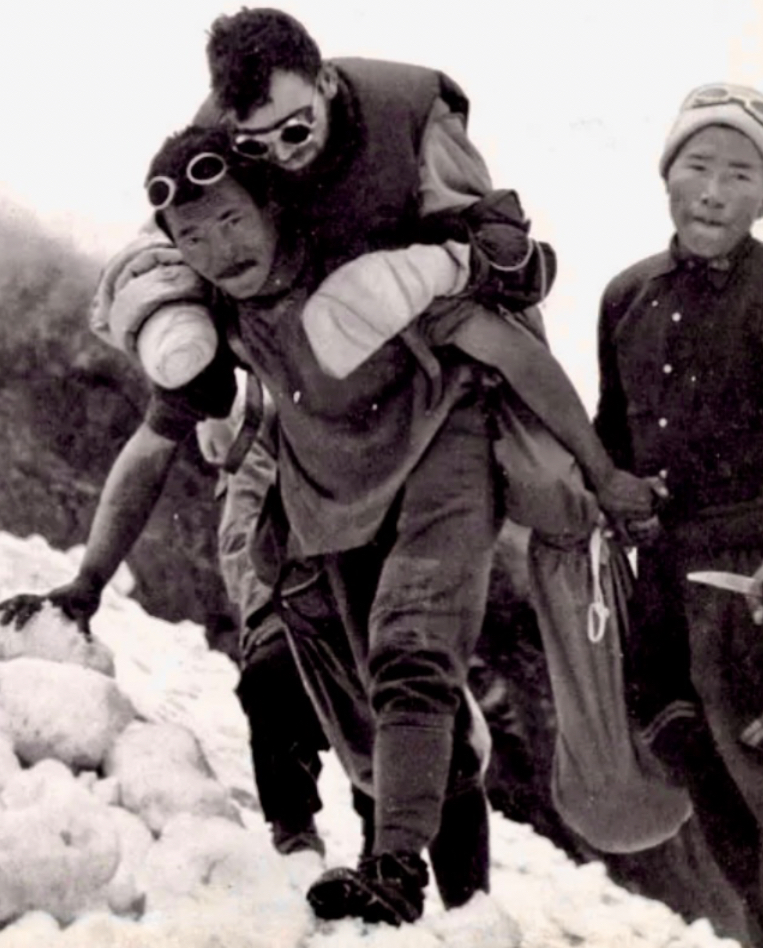

A severely frostbitten Maurice Herzog after the ascent of Annapurna I. Photo: Maurice Herzog

The team

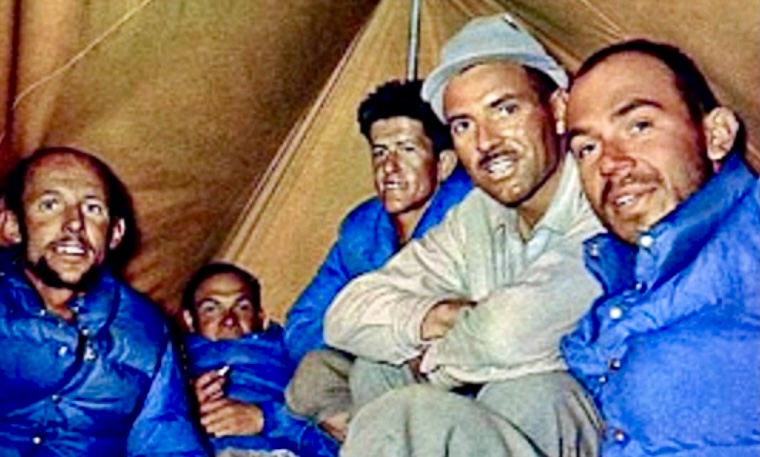

The expedition, organized by the French Alpine Club and approved by the Nepalese government — the first such permission in over a century — included Maurice Herzog (leader), Louis Lachenal (a skilled Chamonix guide), Lionel Terray (a powerful, experienced alpinist), Gaston Rebuffat (another Chamonix guide known for his technical prowess), Jean Couzy and Marcel Schatz (both strong climbers), Francis de Noyelle (a diplomat facilitating logistics), Jacques Oudot (the expedition doctor), and Marcel Ichac (a filmmaker documenting the expedition).

The Sherpa team, which provided critical support during the expedition, included Ang Tharkay Sherpa (sirdar), Ajiba Sherpa, Ang Dawa Sherpa, Ang Tshering Sherpa, Dawa Thondup Sherpa, Ila Sherpa, Phu Tharkey Sherpa, and Sarki Sherpa.

Change of plans

The expedition began in mid-April 1950, with the team traveling from India to Nepal’s Kali Gandaki Valley.

Originally, Herzog’s team had climbing permits for both Dhaulagiri I and Annapurna I. The climbers first set their sights on Dhaulagiri I. From their base in Tukucha at 3,000m in the Kali Gandaki Valley, they explored the area around Miristi Khola river and the east of Dhaulagiri Glacier for potential routes. However, after making a reconnaissance of Dhaulagiri I’s Southeast Ridge and northern side, Dhaulagiri I seemed too difficult, especially with not much time before the monsoon season arrived. Instead, the team decided to shift to Annapurna I.

“As to Annapurna, we knew the northern slopes were accessible, but apart from that, although we had hopes, we could not be sure that the expedition could find a way up. We thought there were three possible routes, but only the glacier route proved practicable,” Herzog wrote in the Alpine Journal.

Time was short. The expedition had to explore, scout, and climb the mountain in a single season, an unprecedented feat.

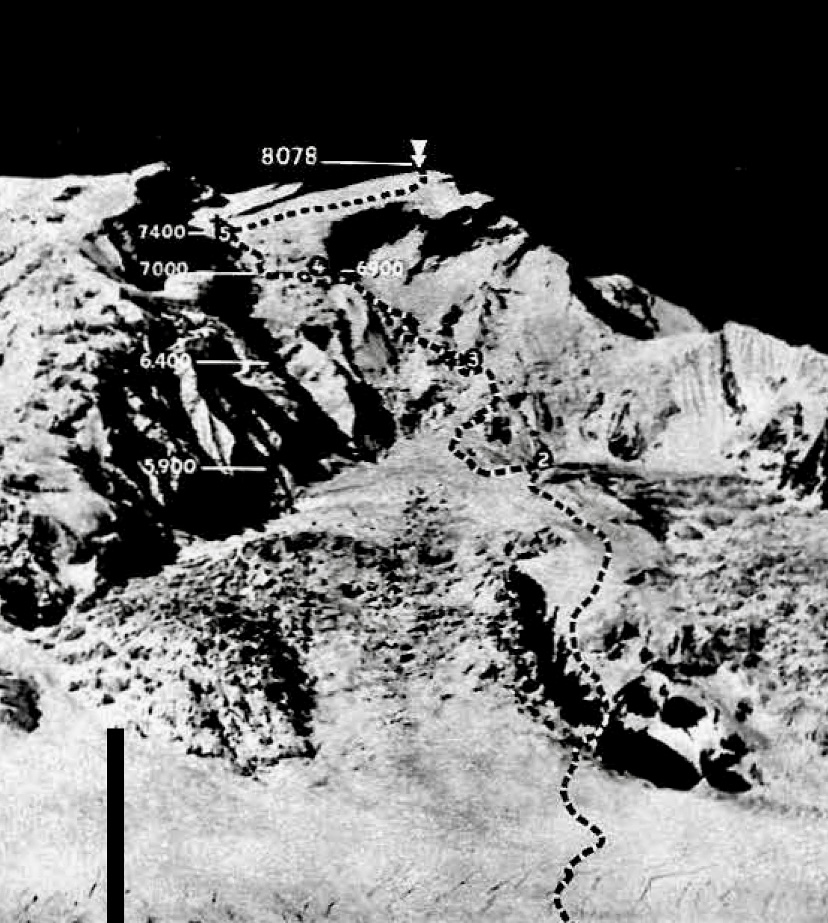

The first ascent route on Annapurna I. Photo: The Alpine Club

Route-finding

The distance between Dhaulagiri and Annapurna is approximately 35 to 40km, and the two peaks are separated by the Kali Gandaki Gorge, one of the deepest gorges in the world.

Herzog’s party arrived in the Annapurna region in early May. The approach offered them several challenges: dense forests and treacherous moraines. The team initially explored the North and East faces of Annapurna I, but the complex terrain and lack of viable routes forced them to reconsider. Herzog, with input from Terray and Rebuffat, decided to focus on the North Face, which offered a feasible but difficult way to the summit.

According to Herzog’s report, the other possibility, the East Glacier route, would have been technically more demanding. Their final decision was critical, as the monsoon’s approach left no room for further delays. The team adopted a siege-style approach, establishing a series of camps to support the ascent and abandoning their initial idea of carrying out a lighter, alpine-style climb. The route reconnaissance involved significant exploration, with key contributions from Terray and Rebuffat, who helped identify a viable line through the complex terrain of seracs, crevasses, and ice walls.

A still image from a video showing the north side of Annapurna. The image shows the various points along the summit ridge, from CO at the east end to Ridge Junction (RJ) in the west. C2 and C3 mark the 8,091m summit. A marks the upper east ridge, B the gully leading to C1. C marks the French Couloir. SFE is the South Face exit. Photo: Joao Garcia with explanation by 8000ers.com and Damien Gildea for the American Alpine Journal

Camps

The route up Annapurna’s North Face began with the establishment of Base Camp at 4,500m on May 18. From there, the team set up five further camps.

Camp 1 was at 5,000m, at the base of the North Face. Camp 2 was at 5,500m, below a sickle-shaped glacier full of crevasses and steep ice slopes. This camp served as a key logistical point, stocked with supplies for the upper camps.

They set up Camp 3 at around 6,000m on a windy snowfield, offering a starting point toward the upper slopes. This was followed by Camp 4, at 6,800m, situated above the rock band on a narrow ledge. Their small, exposed Camp 5 at 7,400m would be the climbers’ last stop before the summit attempt.

Team members during the 1950 expedition. Photo: The Alpine Club

The ascent

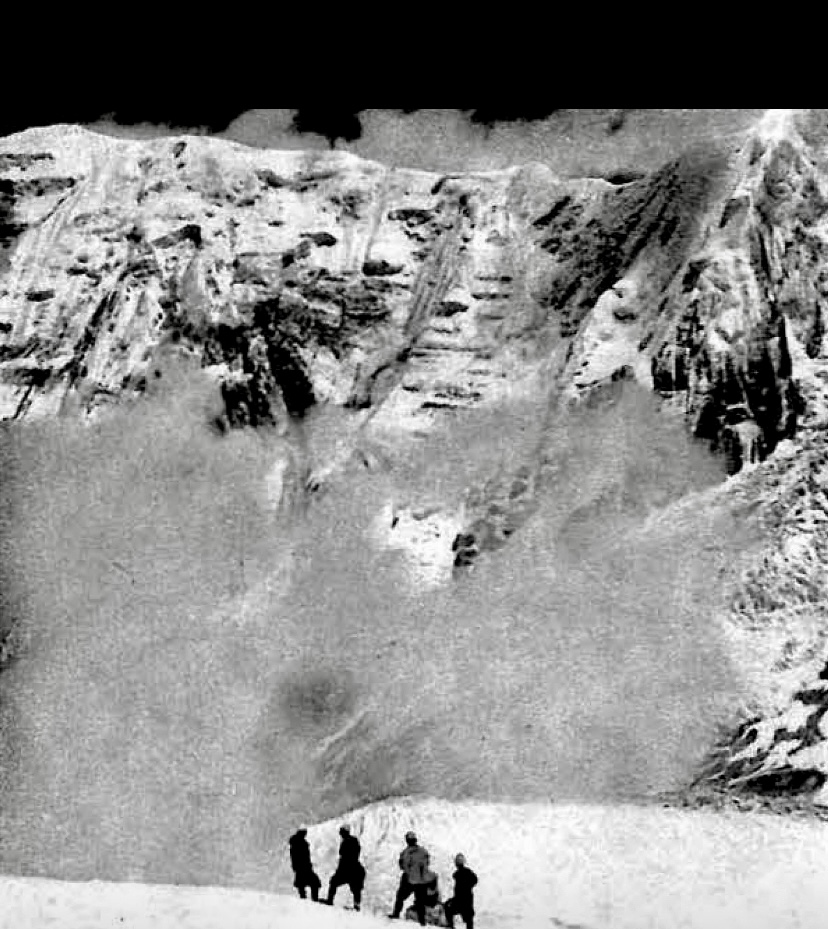

The ascent was grueling. Snowstorms, avalanches, and bitter cold tested the team. The Sherpas, led by Ang Tharkay, hauled heavy loads to stock the camps, while Herzog, Lachenal, Terray, and Rebuffat scouted routes and fixed ropes. The terrain was treacherous, with steep ice, loose rock, and deep snow. Crevasses and avalanches were constant threats. Teamwork kept them going, though exhaustion and altitude strained their spirits.

On June 2, Herzog and Lachenal, supported by Terray and Rebuffat, reached Camp 5. Herzog invited Ang Tharkay Sherpa to be in the summit party, but Ang Tharkay declined, explaining that his feet were starting to freeze.

From left to right: Lachenal, Oudot, Rebuffat, Herzog, and Schatz. Photo: Maurice Herzog

Summit push

On June 3, Herzog and Lachenal launched their summit bid from Camp 5. They started at dawn, climbing without oxygen, through deep snow and fierce winds. Each step of the last 700m was a battle, and the thin air consumed their strength. Lachenal, wary of frostbite, hesitated near the top, but Herzog, driven to reach the summit, urged them onward.

At around 2 pm, Herzog and Lachenal topped out in -40°C, becoming the first people to summit an 8,000m peak.

“I hardly knew if I were in heaven or on Earth, and my mind kept turning to all those men who had died on high mountains and to friends in France. Our moments up there were quite indescribable, with the realization before us that we were standing on the highest peak in the world to be conquered by man,” Herzog wrote in the Alpine Journal.

Herzog took photographs at the summit, planting a French tricolor in worsening conditions. Lachenal, more pragmatic, urged a swift descent as the storm was about to arrive.

A difficult descent

The way down from the summit was where triumph almost turned to tragedy. As Herzog and Lachenal descended, a storm hit the mountain. Herzog lost his gloves, and both climbers suffered severe frostbite on their feet. At Camp 5, Terray and Rebuffat met them. Herzog’s hands and Lachenal’s feet were already severely frostbitten. Rebuffat and Terray warmed them overnight.

On June 4, in a whiteout, the snowblind Rebuffat and Terray tried to descend to Camp 4. Unable to find it, the four spent a harrowing night in a crevasse, sharing a single sleeping bag in freezing temperatures.

A Sherpa carries Herzog down Annapurna. Photo: Mark Horrell

On June 5, during their descent to Camp 2, Rebuffat helped rescue Herzog and two Sherpas from an avalanche. By the afternoon, the team reached Camp 2. Finally, everyone reached Base Camp alive.

“We had beaten it, and I could lie back and think: the job has been finished, the struggle is over,” Herzog wrote.

The North Face of Annapurna I from Camp 1. Photo: Mark Horrell

Amputations

Herzog and Lachenal, unable to walk because of their injuries, were carried by Sherpas across the moraines. Dr. Oudot began treating their frostbite in camp, making multiple amputations without anesthesia to combat gangrene. Oudot saved their lives but at great cost; Herzog lost all his toes and most of his fingers, and Lachenal lost his toes.

Aftermath

They left Base Camp on June 10, reaching Kathmandu a month later and returning to Paris on July 17.

Herzog, Lachenal, and Ang Tharkay were awarded the Legion of Honor, and Marcel Ichac’s film, Victoire sur l’Annapurna, premiered to acclaim. Herzog’s book, Annapurna: The First Conquest of an 8000-Meter Peak, became a mountaineering classic. The book ends with the classic line: “There are other Annapurnas in the lives of men,” which inspired generations of climbers.

However, controversies later emerged. Rebuffat felt Herzog downplayed his contributions, particularly in route-finding, and was dismayed by the expedition’s hierarchical structure. Lachenal’s posthumously published journals (1996) revealed tensions, including his frustration with Herzog’s prolonged summit photography and the official narrative’s omissions.

Ang Tharkay Sherpa. Photo: Dan Bryant/Royal Geographic Society

In his book True Summit, David Roberts revealed that the expedition was marred by internal discord. Herzog’s book portrayed a unified, heroic effort, but Lachenal’s diary and Rebuffat’s writings exposed tensions, including Herzog’s capricious leadership, and the marginalization of Lachenal, Terray, and Rebuffat’s contributions.

In his 1954 memoirs, Ang Tharkay Sherpa wrote that the French members of the expedition treated him with friendship and equality.

The 1950 Annapurna expedition remains a landmark in mountaineering history, a testament to human endurance, but also the price of ambition.