At 4,392m, Mount Rainier is the highest peak in the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest. Situated just 95km southeast of Seattle, it has long beckoned climbers and adventurers. Today, we’ll look into its rich climbing history, spotlighting the pioneers who first approached its icy heights.

An active volcano

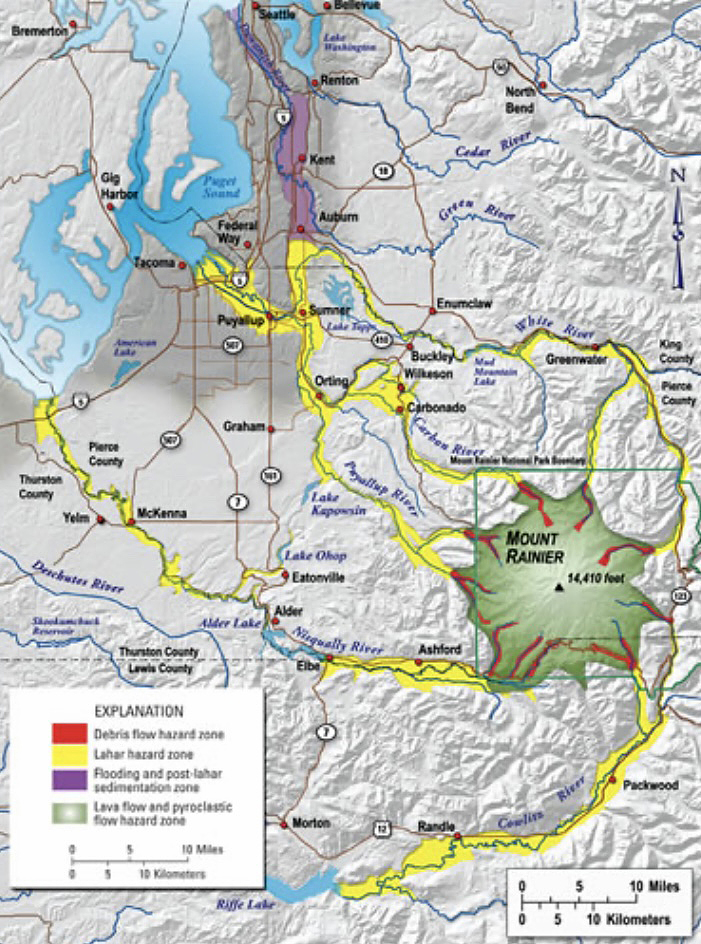

An active stratovolcano, Mount Rainier’s last significant eruption was around 1,000 years ago. (There was some unconfirmed minor activity in the 19th century.) Although it hasn’t erupted for a long time, Mount Rainier is close to populated areas and is considered one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the U.S.

The map shows the areas that could be affected by a Mount Rainier eruption.

Mount Rainier has three distinct summits. The highest is Columbia Crest (4,392m), situated on the crater’s western rim. In 1870, the first successful climbers of Mount Rainier identified this as the main summit. The other summits are Point Success (approximately 4,315m) and Liberty Cap (approximately 4,301m).

Older sources occasionally treat Point Success and Liberty Cap as subsidiary peaks, but modern nomenclature and climbing records recognize all three because of their topographic significance.

Views while descending from Mount Rainier’s summit toward Gibraltar Ledge. Photo: Cascadeclimbers

Cultural significance

Mount Rainier has deep cultural roots for the Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest, whose lands surround the mountain. For these communities, Mount Rainier was not just a physical landmark but a sacred entity tied to creation stories, spirituality, and survival. In various tribal languages, Mount Rainier is commonly known as Tahoma or Takhoma, often translated as “mother of waters” or “snow-covered mountain.”

Archaeological evidence, like stone tools found at the peak, suggests the existence of seasonal camps dating back thousands of years. It is unlikely that climbing to the summit was a cultural practice because high elevations were often seen as the domain of spirits and deities.

Mount Rainier’s summit area. Photo: Wikipedia

First European sighting

In May 1792, English explorer Captain George Vancouver sighted the mountain during a scouting expedition. He named the peak Mount Rainier after Admiral Peter Rainier of the British Navy. The name has caused controversy, with many people believing the name should feature a local figure or have an Indigenous name. However, Mount Rainier has stuck.

In 1833, Scottish botanist William Fraser Tolmie explored the area, seeking medicinal plants. Tolmie was not a climber, but his documentation of the region provided some interesting early insights that encouraged later climbs.

Early attempts

The first documented attempt to climb Mount Rainier took place in August 1857. U.S. Army Lieutenant Augustine Kautz led a team that included Dr. Robert Orr Craig and several Nisqually guides. They started from a low elevation near the Nisqually River and followed what is now known as the Kautz Glacier route.

After eight difficult days of climbing, Kautz’s party reached about 4,267m. Here, they turned back because of exhaustion and health issues. “[We were] too weak to go further,” Kautz wrote.

There was possibly an ascent in 1852, but the climb remains unverified. A brief account in the Olympia Columbian newspaper from September 1852 mentions a climb by one Benjamin Franklin Shaw and other climbers. But details were vague, without route specifics, any detailed description, or firsthand accounts. It’s possible that they reached a high ridge or a false summit, but without more evidence, the ascent can’t be credited as Mount Rainier’s first.

George Vancouver. Photo: Britannica

The first ascent

On August 17, 1870, Americans Hazard Stevens and Philemon Beecher Van Trump completed the first documented ascent of Mount Rainier. Without much prior climbing experience, their achievement marked a significant moment in the mountaineering history of the Pacific Northwest.

Hazard Stevens was a clerk for the Oregon Steam Navigation Company and a Civil War veteran. Van Trump was a government official who worked as a private secretary to the governor of Washington Territory. Both had a keen interest in exploration and the natural world.

The two men had been planning their 1870 expedition for years but were delayed by forest fires in the region.

Mount Rainier from Tipsoo Lake. Photo: Sue Ellen White

James Longmire, an experienced explorer of the area around Mount Rainier, provided critical logistical support for Stevens and Van Trump, including pack horses and guidance. Longmire would not ascend the peak, but his role was instrumental in getting the party to the base.

A Yakama Indian guide called Sluiskin accompanied Stevens and Van Trump to the base of the mountain. He took them to Sluiskin Falls, located at 1,830m, but warned against the climb, fearing supernatural dangers.

English mountaineer Edmund T. Coleman joined the party in Olympia and wanted to summit, but he had to turn back after losing his pack during a difficult crossing of the Tatoosh Range during the approach.

The long approach

The party departed from Olympia on Aug. 8, 1870, traveling southeast toward Mount Rainier. They were accompanied by Coleman and a group of well-wishers who escorted them to Longmire’s ranch on Yelm Prairie, 48km from Olympia.

At the ranch, Longmire provided pack horses. They then proceeded to Bear Prairie, hiring Sluiskin as their guide. Sluiskin was so convinced that the two climbers would perish that he promised to wait two days before reporting their deaths.

Between August 14 and 16, Stevens and Van Trump rested at their base camp and prepared for the ascent.

Mount Rainier. Photo: Caleb Riston

The ascent

On August 17, 1870, Stevens and Van Trump began their climb at dawn. They ascended via the challenging Gibraltar Ledges route, located on the southeast face. This route starts at a low elevation and follows a steep rocky ridge known as Gibraltar Rock, which connects to the upper snowfields and glaciers leading to the summit.

They navigated through loose rock, steep snow-covered slopes, and icy sections, arriving at the crater (at 4,317m) in the afternoon. From there, they made a final traverse to Columbia Crest at 4,392m.

After summiting, night fell, and the weather turned bad. They sheltered overnight in a steam-heated ice cave within the crater.

A difficult descent

The next day, Stevens and Van Trump began to descend early in the morning down the Gibraltar Ledges. On their way down, Van Trump slipped on ice and slid 12m, injuring his thigh but surviving the close call.

Finally, they reached base camp late in the afternoon on August 18, reuniting with their guide, Slusikin.

The duo’s ascent marks the beginning of recorded mountaineering on Mount Rainier.

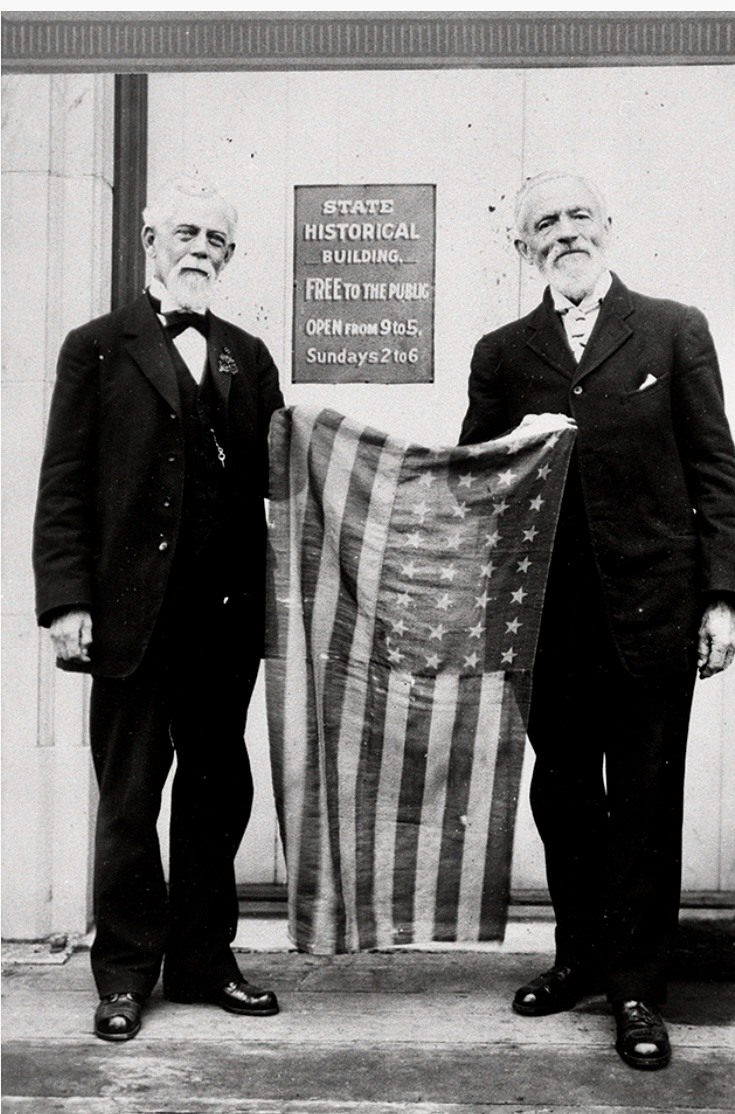

An undated photo taken at the Washington State Historical Society shows Stevens, left, and Van Trump holding the flag they carried on their 1870 ascent. Photo: Washington State Historical Society

John Muir

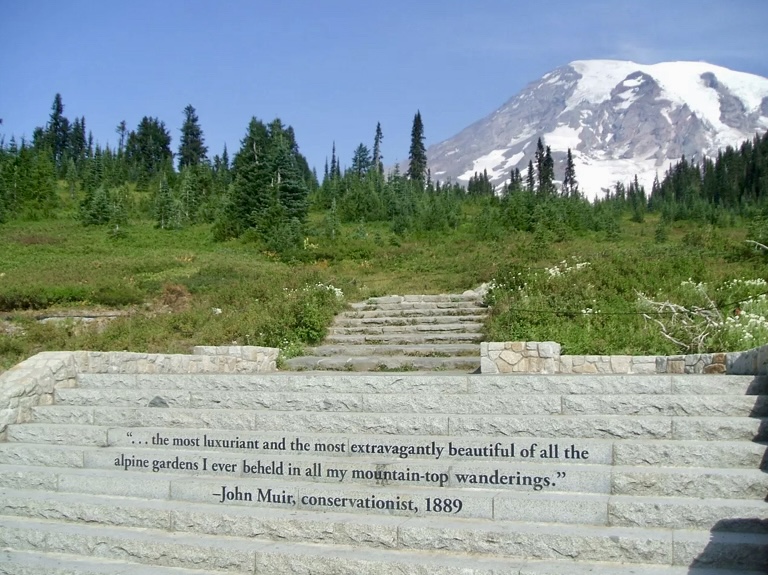

Scottish-American writer and conservationist John Muir summited Mount Rainier in the summer of 1888. He also climbed via the Gibraltar Ledges route. He later wrote about his experience and helped secure the mountain’s protection as a national park in 1899. Muir was struck by Mount Rainier’s extensive glaciers and surrounding wildflower-rich meadows.

“Of all the fire-mountains which, like beacons, once blazed along the Pacific Coast, Mount Rainier is the noblest in form,” Muir wrote.

Other notable ascents

The Gibraltar Ledges route saw its first winter ascent on Feb. 16, 1922. The party was led by Jean Landry and Jacques Landry, possibly alongside Ranger Oliver G. Cornwell and others.

In the autumn of 1935, Ome Daiber, Jim Borrow, and Arnold Campbell summited via the Liberty Ridge route on the north side. Liberty Ridge is Mount Rainier’s most iconic and dangerous route.

The Disappointment Cleaver route is on the southeast side of the peak. Dee Molenaar, Jim Wickwire, and four companions first ascended it on Aug. 23, 1950.

The Muir Steps. Photo: National Park Service

Since its first ascent, thousands of mountaineers have climbed Mount Rainier, which now has over 20 climbing routes.

To date, there have been 370,000-400,000 successful ascents. The success rate is around 50%. The success rate for guided climbs is higher.

Fatalities

Approximately 130 people have died Mount Rainier, including Willi Unsoeld of Everest fame in 1979. Almost every year, there is a fatality.

On Dec. 10, 1946, a U.S. Marine Corps transport plane carrying 32 Marines from San Diego to the Naval Air Station at Sand Point, Seattle, crashed into the South Tahoma Glacier on Mount Rainier’s southwest flank. In stormy weather, the plane hit the mountain at around 3,230m, killing everyone on board.

On June 21, 1981, a massive ice avalanche hit a guided team on the Ingraham Glacier route at 3,353m. A serac collapse triggered the avalanche, which buried 11 of the 29 climbers.

In May 2014, a six-person team was probably hit by an avalanche on the Liberty Ridge route. It killed all six climbers. The team was last spotted on May 28 at 3,962m.

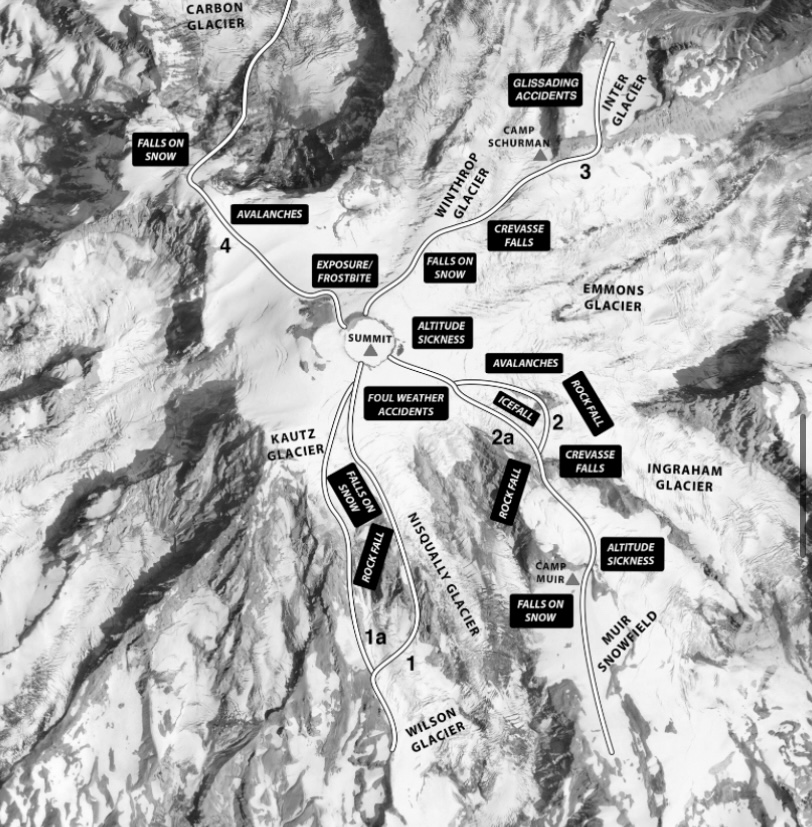

Mount Rainier’s danger zones. Photo: American Alpine Journal