The discovery that Mount Everest — initially an obscure geographical point known only as Peak XV — was the world’s highest mountain was not a single “eureka” moment for one person. It was the culmination of decades of meticulous work by the British Survey of India. This monumental achievement was driven by five central figures.

Lambton’s first baseline

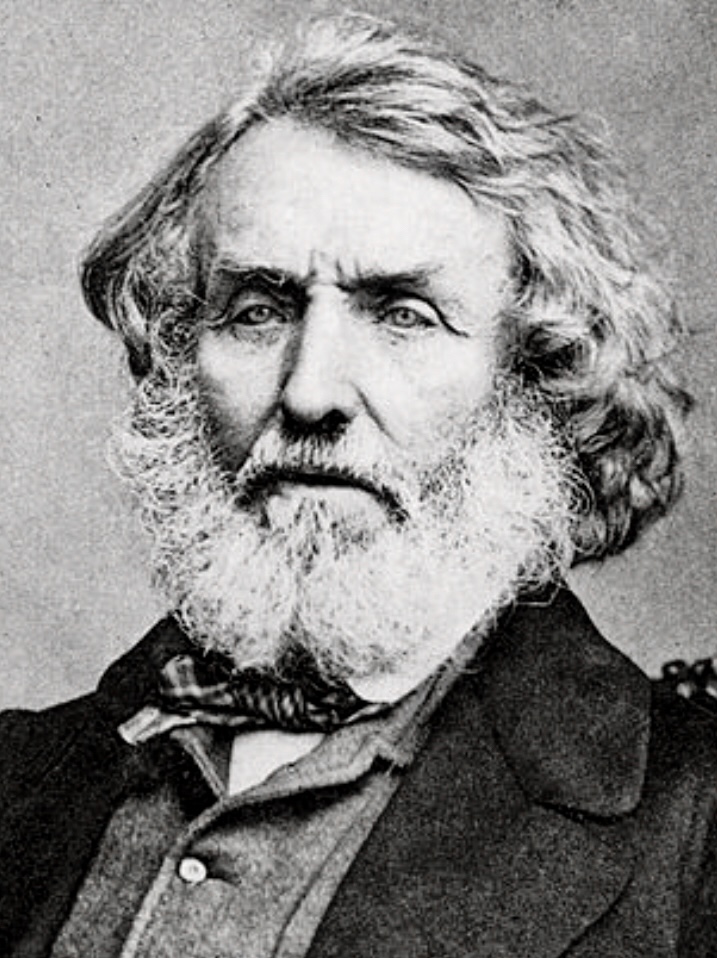

The story of how the height of Mount Everest was established begins not in the Himalaya but on a flat coastal plain south of Madras in the spring of 1802. On April 10 of that year, Lieutenant William Lambton, an infantry officer in the East India Company’s army, started measuring what would become the most famous baseline in the history of surveying.

With a 30.48m-long steel chain, compensated for temperature changes, he and his party spent weeks laying and re-laying out a line slightly more than 12km long between St. Thomas Mount and the village of Perumbauk. They measured every section three times forward and three times backward. The final probable error was less than 5cm.

From that single baseline, Lambton began building a chain of enormous triangles that he hoped would one day run from Cape Comorin to the snows of the north.

William Lambton. Photo: Wikipedia

Lambton’s purpose was twofold: to produce accurate maps for revenue, military, and administrative use, and to measure a meridian arc long enough to improve knowledge of the Earth’s exact shape and dimensions. He called it the Great Trigonometrical Survey.

The work was slow. The triangles often had sides longer than 50km. Stations were placed on hilltops, temple towers, or specially built masonry platforms up to 15m high. Observations were taken only at night or in the early morning when the air was still, and every angle was read dozens of times.

Lambton himself carried the survey north through the Deccan, across the Narmada, and into central India. By the time fever finally killed him in January 1823 near Hinganghat in present-day Maharashtra, the Great Arc had reached latitude 20° 30′ N and covered more than 1,600km. The framework was in place, but the Himalaya still lay far ahead.

George Everest takes command

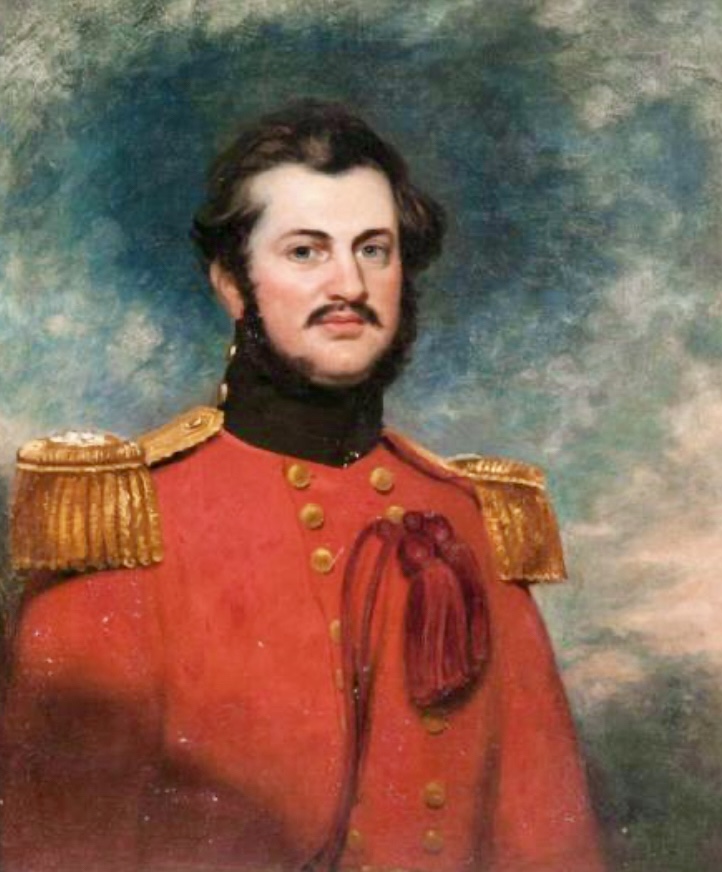

The man who inherited Lambton’s vision and turned it into a machine of almost frightening precision was Sir George Everest. Born in Greenwich in 1790, Everest had arrived in India as a teenage artillery cadet and quickly showed a talent for mathematics and astronomy. He joined the survey in 1818, became superintendent of the Great Arc in 1823, and was appointed Surveyor General of India in 1830.

Where Lambton had been enthusiastic and somewhat improvisational, Everest was methodical to the point of obsession. He threw out many of Lambton’s earlier triangles because they didn’t meet his new standards. He introduced compensation bars to correct for thermal expansion of measuring chains, insisted on observing the same angle on multiple nights, and demanded that every station be occupied by at least two independent observers.

George Everest. Photo: Wikimedia

The giant theodolite

Most famously, he replaced the lighter theodolites previously used. The Great Theodolite built by Troughton & Simms in London stood nearly 1.5m high, had a horizontal circle one meter in diameter, and could read angles to a single second of arc. Moving it required 30 porters and sometimes elephants.

The instrument was so heavy that at one station, it had to be dragged across a river on a raft. Under Everest’s management, the annual advance of the survey slowed to a crawl — sometimes only 50km a year — but the accuracy was unprecedented.

By 1841, the grid had reached the latitude of Dehradun, within sight of the outer ranges of the Himalaya. In 1843, exhausted and half-blind from years of night observing, Everest handed over command and sailed for England. He never saw the greatest result of his life’s work.

The next phase belonged to the field parties who had to work in the Terai, the narrow belt of swamp and jungle that stretches along the southern foot of the Himalaya. The Kingdom of Nepal had been closed to Europeans since the Anglo-Nepalese War of 1814–1816, and no British surveyor could cross the frontier. The only way to see the high peaks was from the Indian side, usually from 160 to 190km away.

The air in the Terai between November and March (when the high peaks were most likely to be clear) was thick with malaria. Observation towers 20 to 30m high were built of bamboo lashed together with ropes. At the top stood a small platform barely large enough for the great theodolite and two observers. They spent their nights in damp tents surrounded by leopards and tigers.

The great theodolite. Photo: Survey of India Archives

James Nicolson’s observations

The officer who commanded these operations in the critical seasons of 1849–1850, and 1850–51, was Captain James T. Nicolson of the Bengal Infantry. Nicolson selected six primary stations spread over a baseline of about 300km: Sandiakaphu in the Darjeeling district (the closest, at roughly 170km from Peak XV), then further west, Harpur, Jiwa Jamuni, Minai, Banog, and others.

From each station, rays were taken to as many as 30 or 40 snow peaks, including the giants later known as K2, Kangchenjunga, Makalu, and the mysterious Peak XV far to the northwest. The horizontal angles were tiny (Peak XV subtended less than one minute of arc from most stations), so every reading had to be repeated scores of times. Vertical angles were even more delicate because refraction could bend the line of sight by several minutes of arc, depending on temperature gradients in the atmosphere.

Nicolson’s health broke under the strain. By early 1850, he was so ill with malaria that he could barely stand. He was carried in a litter to Calcutta and never fully recovered. He died in 1857 at age 37, years before the final height was published.

His field books, however, reached Dehradun safely. Thousands of pages of meticulously recorded angles taken under the flickering light of oil lamps in bamboo towers swaying in the wind.

Bengali mathematician and surveyor Radhanath Sikdar. Photo: Wikipedia

Radhanath Sikdar and the computers

At headquarters in the hill station of Mussoorie and later in the new computing offices at Dehradun sat the men who turned those angles into heights. The most important of them was Radhanath Sikdar.

Born in Calcutta in 1813, Sikdar had graduated from Hindu College, where he studied under the mathematician David Hare. Sikdar joined the survey in 1831 at the personal recommendation of Sir George Everest, who recognized his exceptional mathematical ability.

By the early 1850s, Sikdar was Chief Computer. It meant, in effect, that he was the head of the entire mathematical department. His staff of Indian computers worked in long, quiet rooms filled with the scratch of pens and the smell of ink.

The reduction of Nicolson’s observations was a colossal task. Each ray from each station had to be corrected for instrumental error, for temperature and pressure, and for the curvature of the Earth. Above all, they needed to correct for atmospheric refraction, which at those distances could amount to six or seven minutes of arc and change from hour to hour.

The effect of the Himalayan mass itself on the direction of gravity also had to be estimated. They did their calculations with seven-figure logarithms. It took months. When Sikdar finally combined all the data in 1852, the result was unmistakable: Peak XV stood at least 150m higher than Kangchenjunga and very close to 8,839 meters above the mean sea level at Calcutta.

Andrew Waugh’s final checks

The Surveyor General at that moment was Andrew Scott Waugh, a Scottish artillery officer who had been George Everest’s assistant. He had taken over from the great man in 1843.

Waugh was cautious by temperament. He refused to accept Sikdar’s result without exhaustive checking. He ordered additional observations from new stations. His assistants re-measured some of Nicolson’s rays, and independent computers repeated the calculations.

Only in 1854–1855 did Waugh begin to feel confident. Even then, he deliberately added 0.6m to the computed height, so that the final published figure, exactly 8,839.8m, would not look suspiciously round.

In March 1856, Waugh sent a long letter to the Royal Geographical Society in London. It announced that Peak XV was the highest mountain yet measured and gave its height as 8,839.8m.

In the same letter, he proposed the name Mount Everest, in honor of his predecessor. He explained that the survey had been unable to discover a commonly accepted local name. It was customary to name major features after distinguished former officers. George Everest, at the time 65 years old and living quietly in London, wrote a polite letter saying he would have preferred a native name, but the decision had already been made.

Andrew Scott Waugh, painted by George Duncan Beechey. Photo: Wikimedia

A century at the same height

The 8,839.8m stood as the official height for almost a century. It was refined slightly in 1904–1907 by the use of better refraction tables, and again in the 1950s with improved geodetic data. But the basic measurement from Nicolson’s Terai stations remained remarkably accurate.

Modern determinations, using theodolite triangulation from closer stations in the 1950s, photogrammetry, satellite geodesy, and finally GPS and gravimetry, together with the decision to measure to the top of the permanent snow cap rather than to bare rock, have settled on 8,848.86m as the current official height (China–Nepal agreement of December 8, 2020).

So, the discovery was never a single moment of revelation. It was the end product of a chain that began with Lambton’s steel cable on a coastal plain in 1802, was forged into an instrument of extraordinary precision by George Everest, carried into the malarial swamps by James Nicolson at the cost of his life, computed in the quiet offices of Dehradun by Radhanath Sikdar and his staff, and finally checked, corrected, and announced by Andrew Waugh.

Five men, five very different roles, six decades of institutional labor, and only then did the world learn the exact height of its highest point.

For a deeper journey into the measurement of Mount Everest, we recommend reading John Keay’s The Great Arc.

Mount Everest Base Camp, 2021. Photo: Kenton Cool