I started using iNaturalist in 2018. I had been using the app, a free citizen science platform that defies easy categorization, to record the wildlife I observed as I traveled. A sort of real-life Pokemon. But it wasn’t until 2020 that I was fully hooked.

I was walking through Cat Tien, a sweaty chunk of lowland jungle in Vietnam. I had spent the night at a ranger station set up to protect a critically endangered population of Siamese crocodiles. But it wasn’t the crocodiles that triggered my iNat addiction. It was something much smaller, something I might not have noticed pre-iNat, let alone photographed. On the trail, I found a large land snail and decided to take a couple of snaps of it.

Later, I uploaded the sighting to iNaturalist. For some organisms, the AI identification tool immediately provides an ID with reasonable certainty. For others, it has less information to work with. In these cases, you upload with an ID to whatever level you’re comfortable with. With no knowledge of Vietnamese snail species, I went with the very generic gastropods.

More than a social network

This is when another of iNat’s functions comes in. The app (and website) do much more than serve as a gallery of the things you’ve seen. It describes itself as “an online social network of people sharing biodiversity information to help each other learn about nature. It’s also a crowdsourced species identification system and an organism occurrence recording tool.”

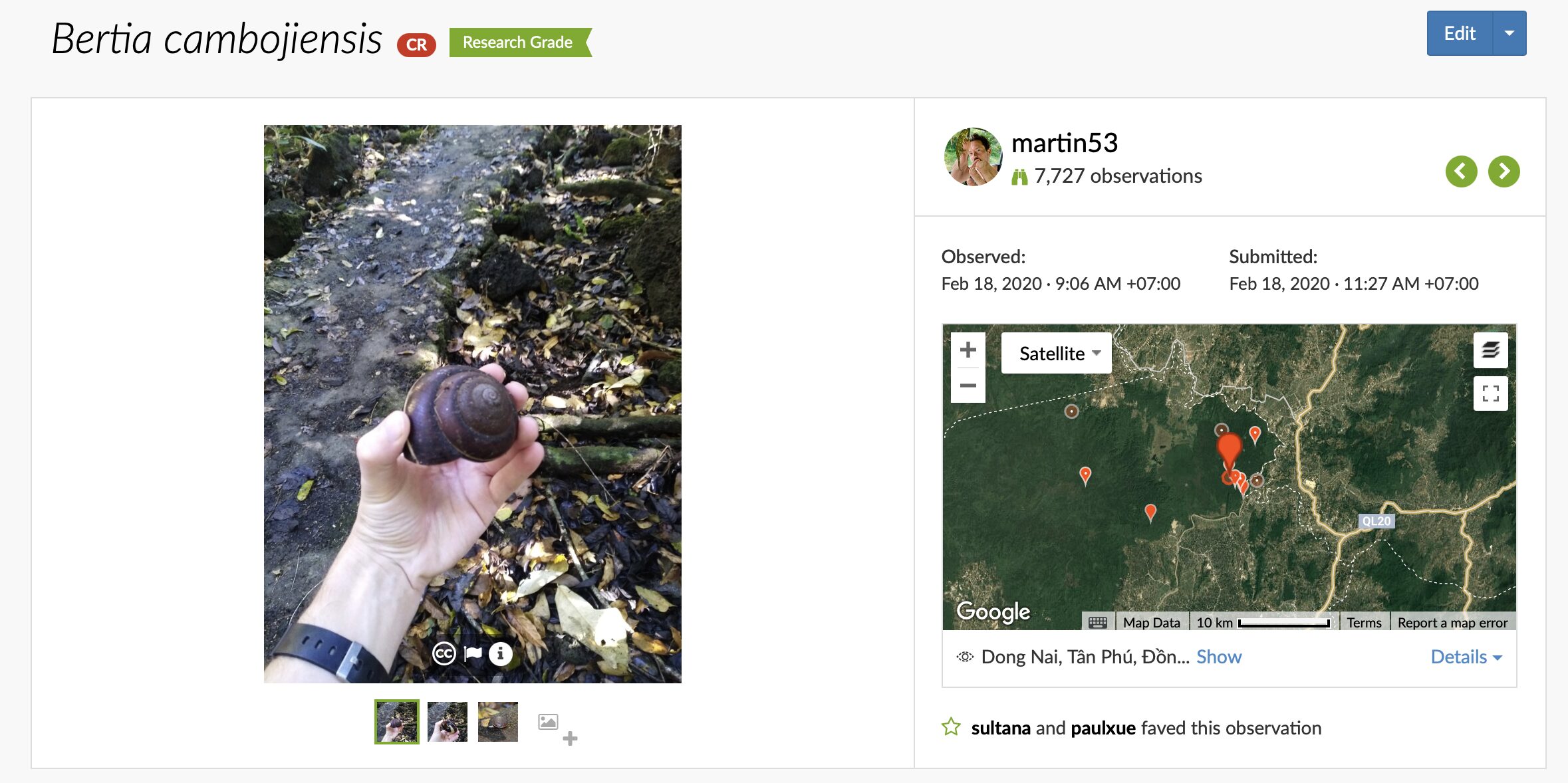

Within a couple of days, other users identified my snail as Bertia cambojiensis, the Vietnamese giant magnolia snail. Critically endangered, this species was long thought extinct and only rediscovered in 2012.

My observation of ‘Bertia cambojiensis.’

From there, it was a slippery slope. Within a year, I’d bought a large camera and some proper binoculars. Soon, I was reading research papers on species splits and primate behavioral studies. Last week, I was chatting to a lepidopterist (someone who studies moths/butterflies) in Colombia who wanted to know if she could use one of my photos for a field guide. I’m 2,400 species deep and still going strong.

And that’s the thing: iNaturalist makes you look at the world differently. It encourages you to take in what’s around you, to explore, and to learn about what you find. Unlike eBird, which has been around much longer and also collects crowd-sourced data, iNat deals with all life: plants, birds, mammals, reptiles, viruses — if it is wild, upload it. This breadth encourages learning, and it encourages a more holistic view of the natural world.

Fancy getting addicted, too? Here’s a quick explainer on how to use iNaturalist.

Getting started

It might be helpful to think of the three elements of iNaturalist as different levels of interest.

Do you just want a quick AI-driven ID of something in your garden? Try the Seek app, made by the same company. This is the most basic version of what iNaturalist offers. Point your phone at a flower, take a photo, and the image recognition software will try to tell you what it is. You don’t have to upload the observation (but you can!).

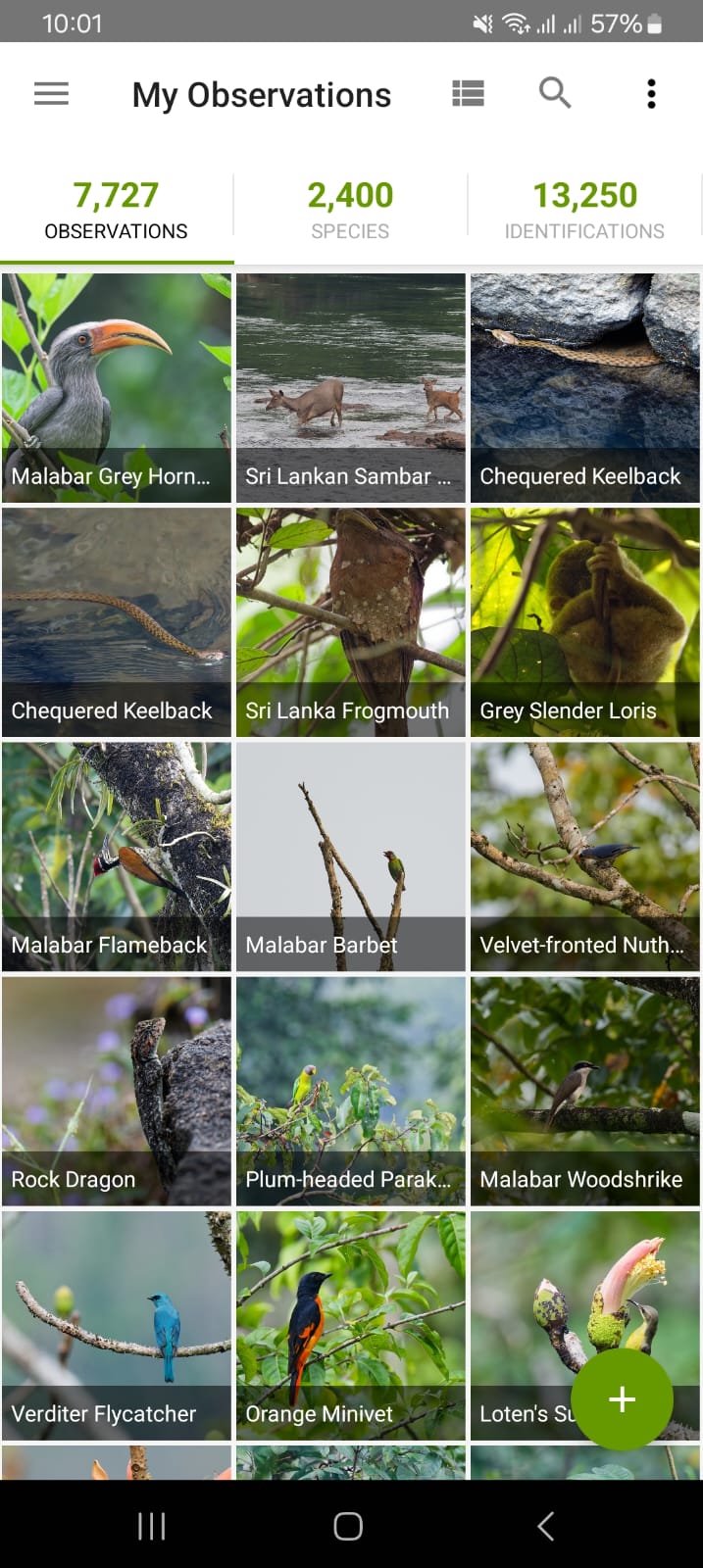

Want to track what you’ve seen and contribute to science? Then, the iNaturalist app is better for you. It will track what you’ve uploaded, allow you to explore other people’s observations from around the world, and provides most of the functionality of the website. You can find the Android app here and the iPhone app here.

A screenshot of the iNaturalist app on Android.

Want the full package? The website is best if you want to do all of the above and also help others to identify their observations. I use it to learn, plan trips, and help out by identifying birds and mammals in Southeast Asia, where fewer users have the requisite knowledge.

The iNaturalist website, showing my observations on a world map.

Making an observation

To make an observation, you need a few things.

- A photo or a sound recording.

- When (date/time) you saw the organism. This is usually added automatically from a photo’s metadata.

- Where you saw the organism. This can be added automatically if you’re taking the photo on your phone. Otherwise, you will need to do this manually using the map.

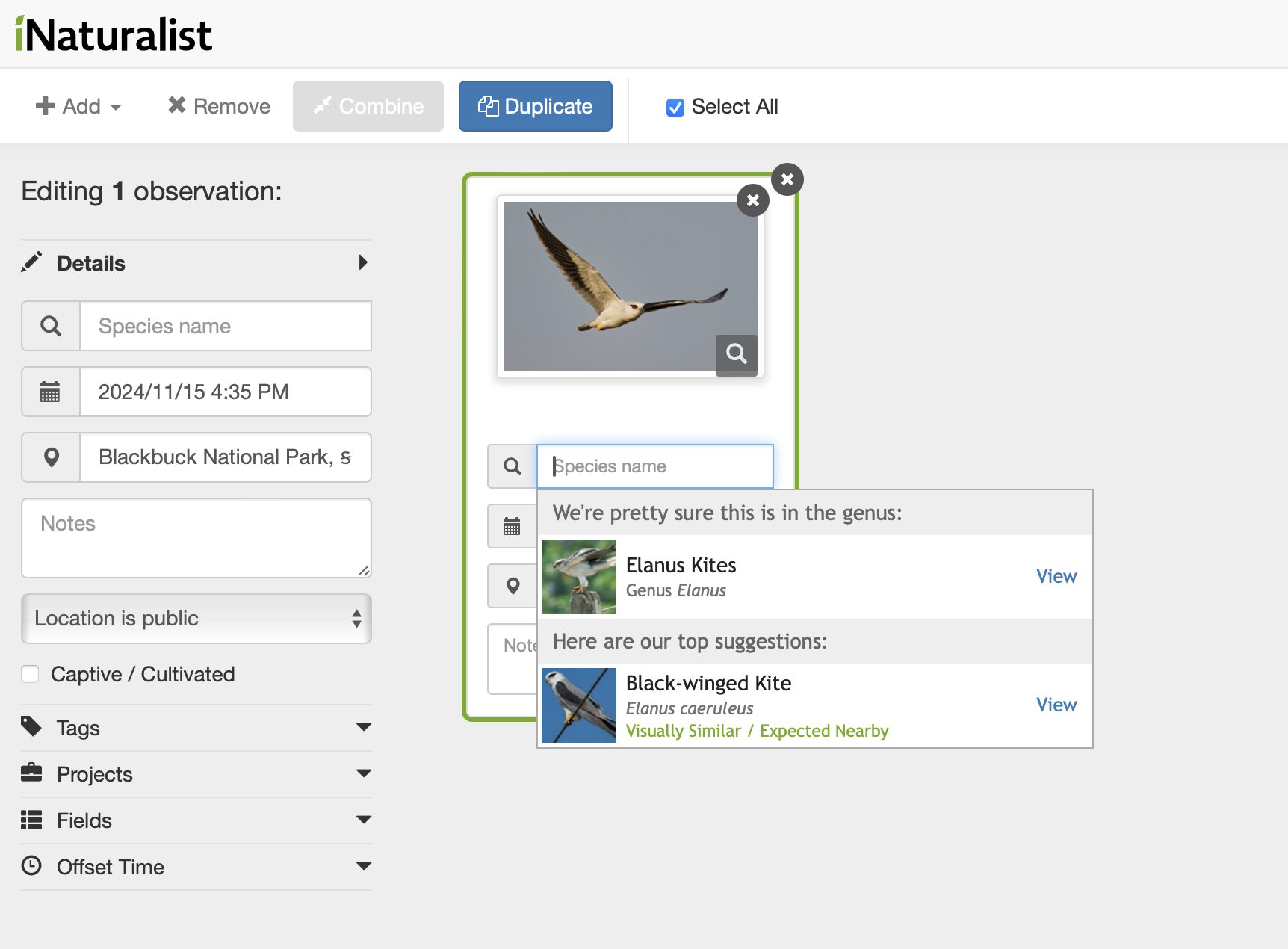

- What did you see? The AI will offer suggestions. Sometimes, it will say: “We’re pretty sure this is…” with a single suggestion. If this matches what you observed, select this. Other times, it won’t be so sure: “Here are our top suggestions.” In this case, it is best to only ID to a level you are sure of — eg. You’ve seen a woodpecker but you’re not sure of the species? Type in woodpeckers and select the family group. It’s always better to go with a coarse ID like “Birds” or “Mammals” rather than guess what something is.

- Was it wild? Is it a pet/zoo animal/cultivated plant? Then tick the captive/cultivated box.

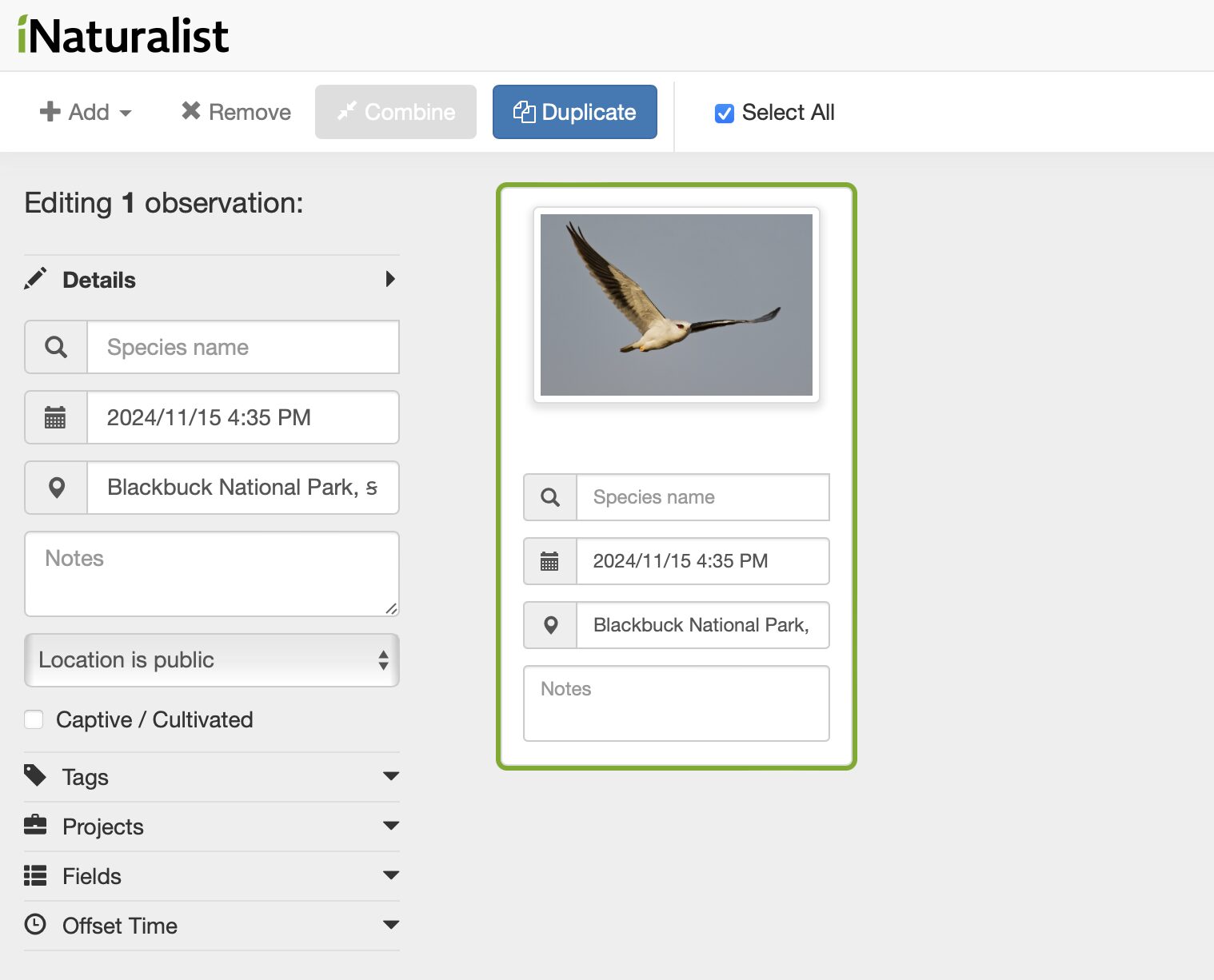

Adding an observation through the website. I added a photograph, and the date and time were automatically populated from the photo’s metadata. I then added a location in the third box: Blackbuck National Park.

In this screenshot, you can see the AI image recognition trying to determine the species. In this case, it only recognizes up to the genus level (Elanus kites). However, the top suggestion is the correct species. Users who don’t know the species should only follow the ‘We’re pretty sure this is…’ suggestions. Other users will then help ID the species.

Got old wildlife photos? You can upload historical records, too.

iNaturalist has a detailed step-by-step guide to making observations here.

Citizen science

If an observation reaches “Research Grade” (has all the data listed above and the ID is agreed upon by at least 2/3 of identifiers), then scientists can use it. You might see your observations included in a research paper or upcoming study.

Occasionally, iNaturalist leads to the rediscovery of a species or the discovery of new ones. This month, a London commuter uploaded an invasive insect not seen in the UK for 18 years. Last month, a marine worm was rediscovered after 68 years when researchers spotted it photobombing seahorses, and a user spotted a humpback whale in New York’s East River!