On January 26, 1950, a military aircraft took off from Anchorage on a routine flight to Montana. On board were 41 military service members, a civilian technician, and a young mother with her toddler son. Neither plane nor passengers were ever seen again.

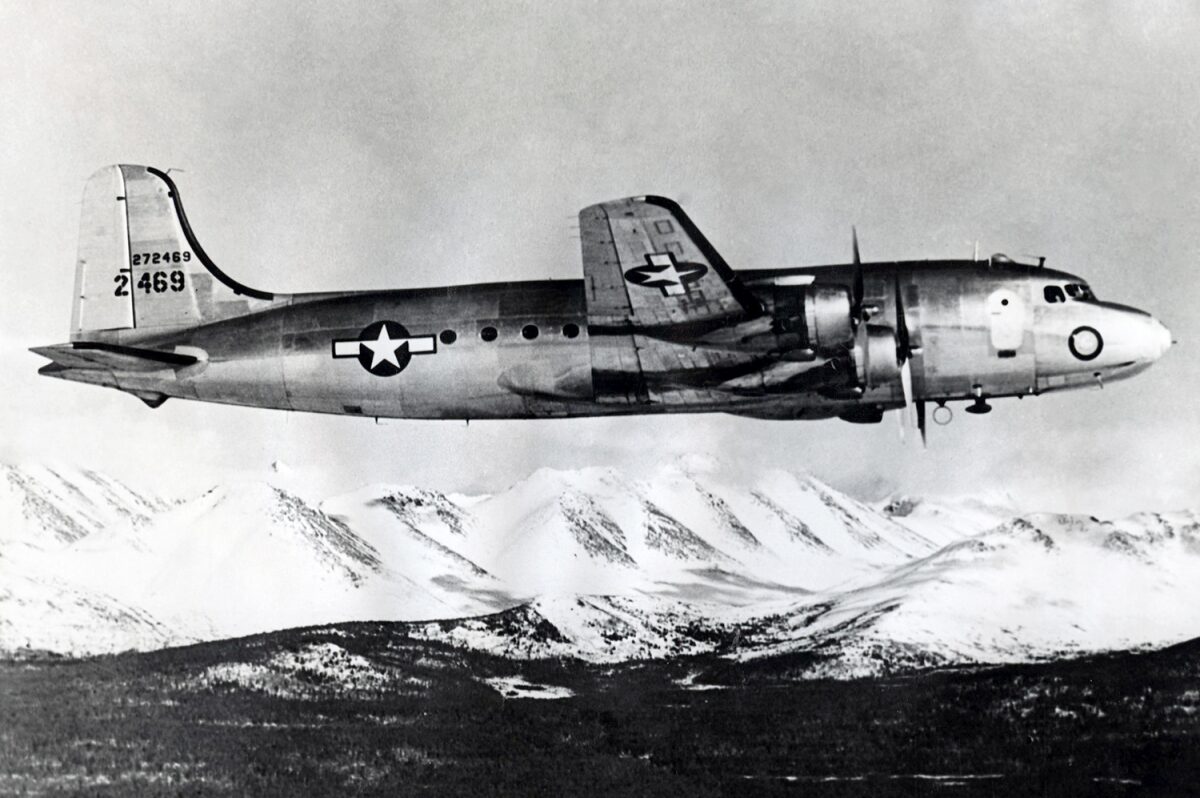

Designated USAF Flight 2469, it crossed the Alaska-Canada border two hours after takeoff and went down somewhere over the Yukon. Now, 75 years later, the Douglas C-54D Skymaster lies wherever it landed, with the fate of those on board still weighing heavily on the families.

As a military flight, the details of the incident were carefully recorded and filed in now-public reports. This is what we know:

At 9:16 pm on January 26, the pilot, 1st Lieutenant Kyle E. McMichael, was cleared for takeoff from Elmendorf Air Force Base outside Anchorage, Alaska. The commanding officer aboard was Major Gerald Brittain. There was fog but no wind, and the weather conditions were not considered hazardous.

At 11:09 pm, the Skymaster reported its position, just over the small Yukon town of Snag. Just three years earlier, Snag reported the lowest recorded temperature on the North American continent, at -62.2 °C (-80 °F). The plane’s altitude was 10,000 feet, or about 3,000 meters, with some ice conditions and a strong tailwind of 60 to 80mph (96 to 128 kph). At that time, they reported that they were proceeding as planned toward Whitehorse. They were to check in again by radio as they flew over the Yukon capital.

Finally, at 3:05 am, the Skymaster was reported missing when it failed to arrive at its destination in Great Falls, Montana.

A massive search began immediately.

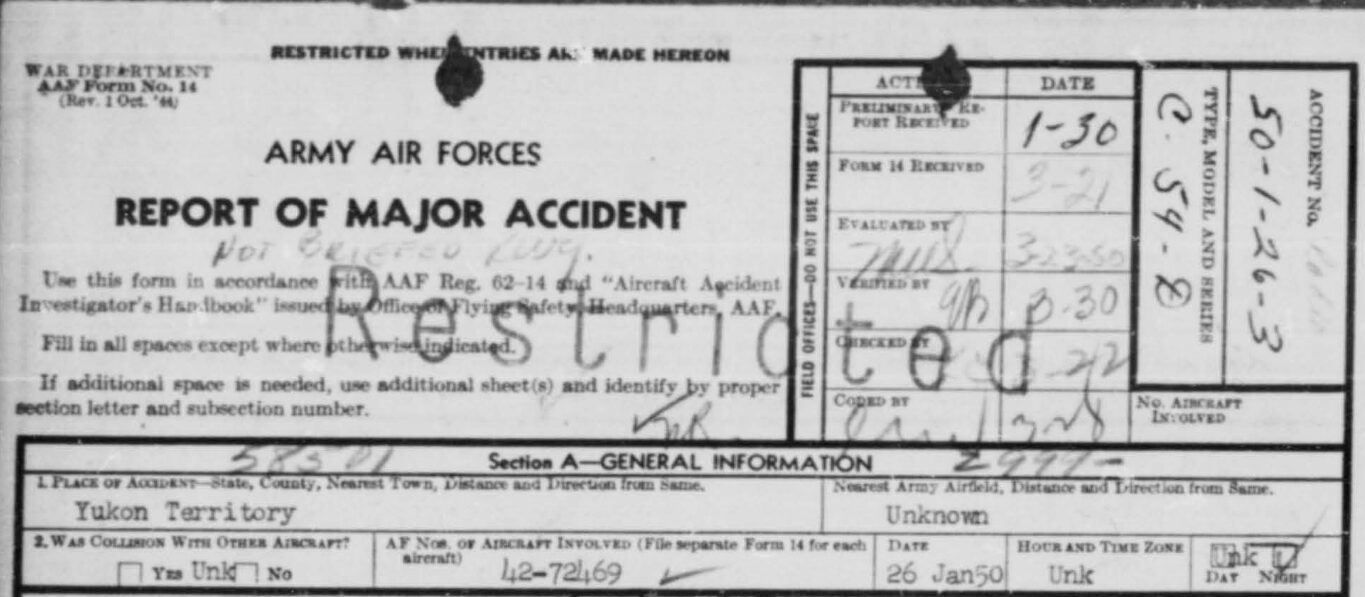

Most of the fields in this report are marked unknown. Photo: USAF C54D Skymaster 42-72469 Accident Report

Operation Mike

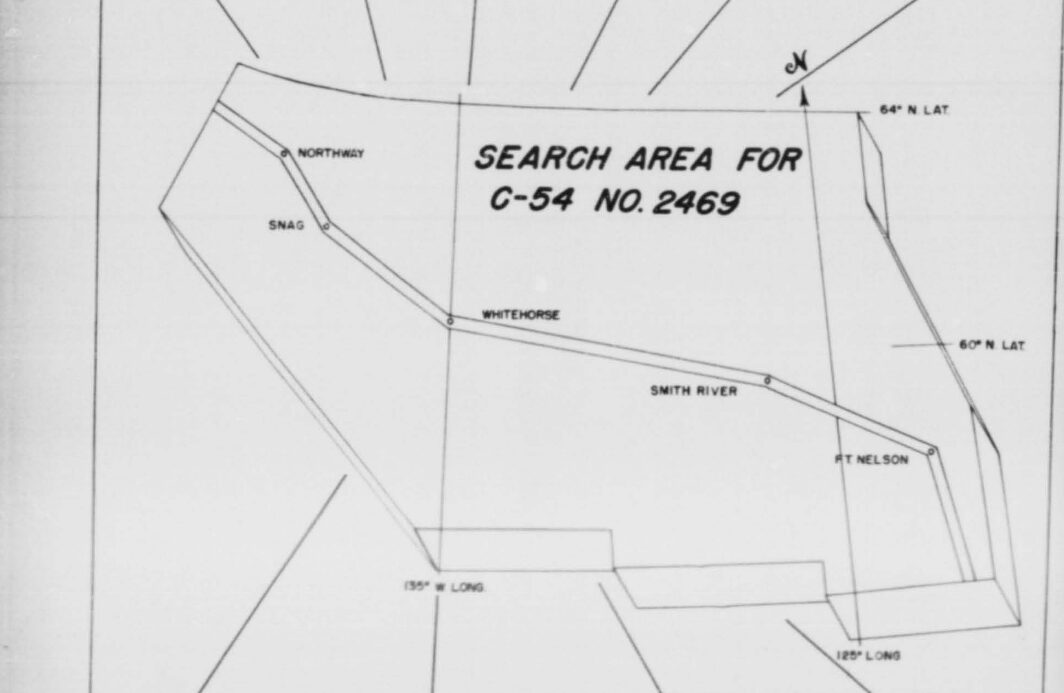

The search operation was named Operation Mike after Lt. Kyle McMichael, Flight 2469’s pilot. Officials assumed the plane went down somewhere along the 400 kilometers between Snag and Whitehorse.

A coordinated ground and air operation began between the U.S. and Canadian forces. They set up an emergency center in Whitehorse. Within 20 hours, they had 25 aircraft at their command. Coincidentally, a joint U.S.-Canadian arctic exercise, Operation Sweetbriar, was planned for that week. The 20,000 troops went instead to Operation Mike. In the first three days, planes searched 88,500 square kilometers.

An illustration from the 1950 report shows the area covered in the search. Photo: USAF C54D Skymaster 42-72469 Accident Report

A dangerous search

But the weather continued to worsen over Whitehorse. Many aircraft could not take off, and the visibility for those that could was limited.

“Weather has been a constant handicap,” reported Sgt. Brady, in a restricted communication. “The general search effort has decreased in all sectors.”

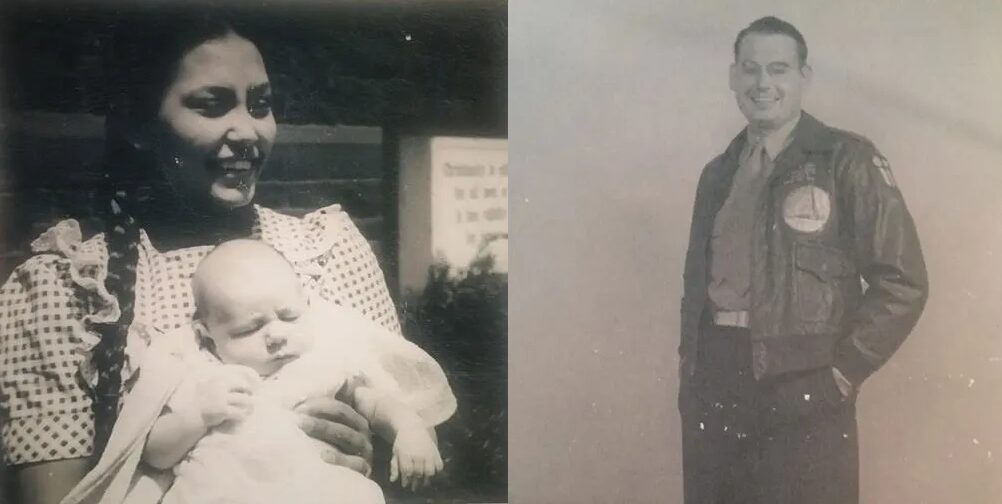

One of the most determined searchers was Master Sgt. Robert Espe. His 23-month-old son, Victor, and his pregnant wife, Joyce, were two of the missing passengers.

The weather continued to hamper the search. On January 30, a C-47 Dakota with nine men aboard was scanning the Whitehorse area when the pilot, 1st Lieut. Charles Harden, misjudged his altitude. The plane crashed in the mountains. Fortunately, injuries were minimal, and Lieut. Harden went on foot for help. He only had to walk a little over six kilometers before he reached a highway and was able to flag down a truck.

The Yukon continued to show why its weather and remoteness made it so dangerous for aircraft. On February 7, a second Dakota went down, also without casualties. The need to rescue the rescuers further strained resources.

One of three planes that crashed during the search for the missing Skymaster. Photo: Andrew Gregg

Smoke signals

On February 1, Espe and the other family members got a ray of hope: a distress signal that seemed to be from the Skymaster.

The missing aircraft was fitted with a Gibson Girl emergency transmitter, and ground stations had been set up all over the area hoping to catch any signals. The first one was a dud, however. It had come from a ship-to-shore band, not from the Skymaster.

“Feelings of the RCAF is that results of this radio search will be nil,” Sgt. Brady confided in another communication. “The current question on everyone’s mind here is, are we justified in continuing?”

The next day, several more leads emerged. A Canadian Pacific Airlines pilot reported smoke signals in the Rocky Mountains on the border between Alberta and British Columbia. Could the flight have gone so far off course? At the same time, RCAF pilots were interviewing a witness at Williams Lake, far to the south in central British Columbia. The man was a hunter and claimed that he had heard a large plane flying low over his cabin on the night of the 26th.

Joyce Espe and her son Victor, left, were on the flight. Robert Espe, right, searched for them for the rest of his life. Photo: Andrew Gregg

Diminishing hopes

Even supernatural leads were taken seriously, or at least recorded for posterity. On February 3, a French Canadian prospector named Gautron walked into the search headquarters and said that he was sensitive to metal objects and had been receiving “shock waves” since the plane went down. The location of the wreck, he said, was a few kilometers from Watson Lake, on the Yukon-B.C. border.

A woman in Arkansas also sent a telegram claiming to have had a dream that the wreck was in Dark Horse Canyon. Another anonymous letter writer claimed to have received a telepathic message: The plane was in the bush outside Revelstoke, B.C. and they were running out of food. Someone named John had frozen feet. Nothing came of this.

On February 10, they caught another distress signal. This one was on the Yukon-B.C. border, and the operator thought he heard the words “Watson Lake.”

Searches, of course, found nothing, and no other distress signals came through.

The C-47 Dakota which crashed and was briefly missing. Incidents like this complicated the search for the Skymaster. Photo: The Windsor Daily Star

The search abandoned

For weeks, their efforts had gone unrewarded, while massive resources were expended on what seemed like a forlorn hope. By February 1, they had covered 90% of the most likely areas, and the weather remained bad. Operation Sweetbriar, the training exercise, was still going forward, so men and planes loaned to Operation Mike were no longer available. Then a much better-known aviation disaster drew eyes from the Skymaster.

On February 13, a B-36 bomber with an atomic bomb on board left Alaska. Three of the four engines failed. They were forced to detonate the bomb over the Pacific Ocean and then bail out. By then, Operation Mike had shrunk significantly from its peak of 85 active aircraft and 7,000 searchers.

A final false hope came from an Indigenous trapper named Albert Isaac, who reported hearing an explosion on January 26, which triggered an avalanche. He and his son had heard the sound, which was “like thunder,” and saw carrion birds circling. But a search of the area found nothing.

Defeated RCAF searchers told reporters that the search area was “a sea of complexities, gully after gully that could have swallowed the plane and buried it in snow.” They had covered 569,925 square kilometers and found nothing. On February 20, Operation Mike formally ended, and the missing passengers were declared dead.

Family members of missing co-pilot Lieut Mike Tisik gather around the radio waiting for news. Photo: Skymaster Down

What could have happened?

What, exactly, caused the demise of the Skymaster remains unclear. It had over 13 hours of fuel aboard, and at takeoff, the weather had not caused any concern.

The only worrying conditions were over Whitehorse, where it was overcast to 2,286 meters, with 48 kilometers of visibility and ice in the clouds. The weather did worsen by the time the search commenced, but it had not grounded any aircraft when the Skymaster was in the air.

If not weather, it could have been equipment failure. In fact, the Skymaster had attempted to take off hours earlier but had been unsuccessful. Mechanics found a fault in one of the four engines and repaired it, and the second takeoff had gone smoothly.

It’s always possible that the true cause of the failure remained undetected, and the problem resurfaced at the worst moment. With an unpressurized cabin, the plane couldn’t safely fly above around 3,000 meters. Over a dozen peaks in the Yukon soar beyond that height.

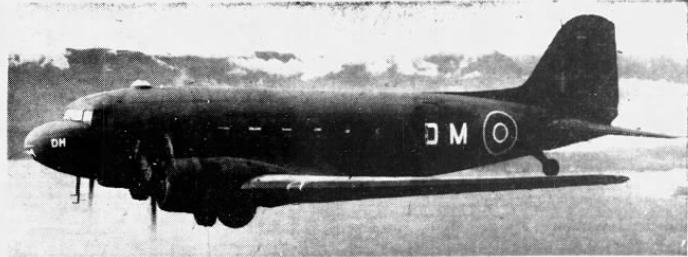

While it is difficult to tell in black-and-white photos, the Skymaster planes were painted bright red, which should have stood out against the snow. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Waiting in vain?

Perhaps the most troubling possibility is that there were survivors. If the plane made an emergency landing rather than outright crashed, then all 44 of the passengers might have waited for help that wouldn’t come. The pilots likely would have tried to land on the flat surface of a frozen lake. But when spring came and the ice melted, the plane would have simply sunk to the bottom, making it impossible to find.

If there were survivors, they may have lingered, trapped in the vast wilderness, long after the search had been called off. According to the crash report, the plane had been equipped with arctic survival equipment and 10 cases of rations. The crew had also received arctic wilderness survival training.

The survivors of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, which famously crashed in the Andes in 1971, were able to hear on their radio that the search for them had ended. In their case, they were rescued after two men — Roberto Canessa and Nando Parrado — hiked out of the mountains to fetch help. It is possible that a similar party, sent out by Skymaster survivors, had been less lucky.

These are the types of calculations that haunted the loved ones of the missing passengers. It was too late for rescue; but not too late for closure.

The Yukon had many plane crashes in the first half of the twentieth century. While most of them have been located, the Civil Air Search and Rescue Association helps find the missing wrecks. Photo: CASARA

The new search

In recent years, renewed interest in the mystery has spurred new search efforts. The release of a documentary called Skymaster Down was particularly influential. In 2022, the Skymaster 2469 CAN/AM Society was founded. Its hundred members volunteer their time and expertise to search with satellite imagery for potential crash sites.

While relatively new, there is an emerging class of internet detectives using satellite imagery to find wreckage. People like Randall Osczevski, a retired scientist whose hobby is hunting down plane crashes and lost expedition clues in grainy satellite images of the Arctic. The difficulty and expense of checking potential sites in the field is a major obstacle to progress, he says.

The Skymaster 2469 CAN/AM Society knows this. That’s why the group also makes annual trips to search by air, funded entirely by donations and staffed by volunteers. In 2025, they hope to expand into ground searches as well. Working with them is the Civil Air Search and Rescue Association. CASARA is a Canada-wide volunteer aviation association, which provides air support in searches for downed aircraft.

Andy Rector, Michael Rocereta, and Spring Harrison of the Skymaster 2469 CAN/AM Society take part in a search. Photo: Andy Rector

Hope remains

If the Skymaster was frozen in a glacier, it would be much harder to find– unless the glacier starts to melt. One of the silver linings of climate change: As glaciers shrink, more hidden wrecks surface.

In 1952, only two years after the Skymaster vanished, a Air Force C-124 flight with 52 men aboard crashed in the Alaskan wilderness. For 60 years, their family members hoped in vain that their remains could be found and recovered. Then in 2012, a routine training flight spotted the wreckage, freshly emerged from Colony Glacier. After 10 years of recovery missions, the remains of 44 victims have been identified and returned to their families.

Recovery efforts on the Colony Glacier. Photo: U.S. Department of Defense

It may be only a matter of time until melting ice releases its grip on the lost Skymaster. But the searchers aren’t content to wait and hope.

“We’re continuing to search,” promises Andy Rector, a founding member of the Skymaster 2469 CAN/AM Society. “We haven’t given up here… because of the families and getting closure for them.”