Some of the best adventures are born over a beer, and British chef Mike Keen is a prime example. While chatting with a colleague in a bar in Nuuk, Greenland, Keen mused about the challenging Greenlandic language, especially the abundance of Q’s. This casual conversation sparked an ambitious idea: to embark on a kayaking journey from Qaqortoq in the south all along the west coast to Qaanaaq in North West Greenland.

While spending six summers working in Greenland’s restaurants, Keen had dabbled in kayaking during his free time, but he was far from seasoned. He had never combined camping with kayaking. After a divorce and a grueling stint of 100-hour weeks in a British pub, Keen decided to channel his newfound freedom into something big. He poured his energy into raising funds and crafting a unique twist for his ambitious adventure.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, the British chef had been deep into writing a book about fermentation techniques in cooking. Inspired by this project, he decided to blend his kayaking adventure with a culinary experiment. He would eat like traditional Inuit did, solely on sea mammals and fish.

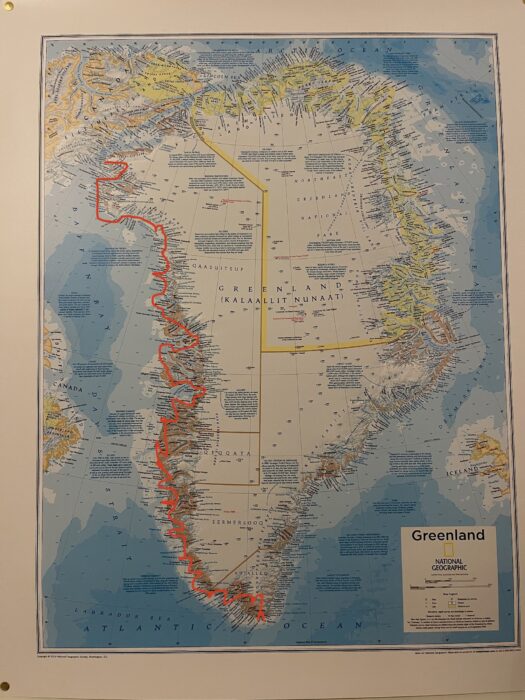

Keen’s route in red. Photo: Mike Keen

Barred by ice

Keen started on his adventure from Qaqortoq in April 2023 after a two-week delay due to stubborn sea ice. The spring was colder than usual, dropping at times to about -10°C. Despite his limited experience, the British chef made steady progress along the first third of the coastline. However, the waters around Nuuk presented a new challenge with strong tidal currents and sea ice that he hacked a way through with an ice axe taped to his paddle. He had also previously battled rough seas near Paamiut.

About to leave Qaqortoq. Photo: Mike Keen

Adhering to his Inuit-inspired diet, the British adventurer carried just 5 to 10 days of food at a time, replenishing his supplies in coastal villages. Local hunters often generously donated food, especially big portions of seal meat. He cooked the seal in local kitchens, then packed it along with dried fish and whale meat for the next leg of his journey.

As Greenland TV began to cover his journey, Keen often found himself with a cozy bed for the night. He estimates that during the first leg, he camped just half the time and was graciously hosted by locals for the rest.

Unfortunately, this part of the journey concluded after covering roughly two-thirds of the distance — 95 days and 2,100km — at Upernavik. Locals informed Keen that he couldn’t proceed through the vast expanse of sea ice and iceberg-choked Melville Bay.

The crux: Melville Bay

Unable to bear the cost of waiting in Upernavik for the ice to clear, Keen headed back to the UK to regroup and plan to pick up the following year where he left off. The setback was particularly disheartening because he had collected letters from locals at the journey’s start, with the promise of delivering them further up the coast, a nod to traditional Inuit postal routes.

A drone image of Keen paddling through Melville Bay. Photo: Mike Keen

In July of this year, Keen returned to Upernavik with a renewed determination to reach Qaanaaq. This time, for safety, he arranged for a small support boat to follow him across the vast, open waters of Melville Bay. Fortunately, the sea ice was manageable enough to allow steady progress. For the first two days, Keen covered a strong 60km each day, staying close to the coastline until he was pushed out to sea toward Canada while trying to find a route through the maze of sea ice.

A polar bear crosses sea ice near Savissivik. Photo: Mike Keen

Support boat

Without hesitation, he called in the support boat to tow him back toward the shore for the night, where he slept on the boat. Keen operated on his own terms without the pressure of adhering to notions of support that would count against him if he made claims on the style of journey or sought records.

The next two days beyond Melville Bay were without hazard. Unlike the earlier part of his journey, there were no villages to stop at, forcing the British kayaker to camp wherever he could find somewhere to beach along the rugged coast.

To his surprise, Keen encountered just one polar bear during his journey, though he found himself more worried about potential walrus attacks. He carried a rifle for much of the trip and used a homemade alarm fence a few times but usually didn’t bother.

An island in Melville Bay. Photo: Mike Keen

The British chef-turned-kayaker parted ways with his support boat at Savissivik, ready to tackle the rest of the journey solo. Along the way, he often set up camp beside ancient Inuit stone circles, though he never stumbled upon other historical landmarks. One notable stop was at the American Pituffik Space Base, formerly known as Thule Air Base, where Keen treated himself to a night’s rest on an old military spring bed — an unexpected comfort in the midst of the more remote northwest coast. A hunter and his wife used their residents’ permissions to allow the Briton to enter the restricted base.

Homecoming in Qaanaaq

After 19 days on this second leg and 114 days in total, Keen finally paddled into Qaanaaq, completing his 3,200km journey. In this remote town, the British adventurer received a hero’s welcome from locals who had been following his adventure in the media. Keen won the hearts of the community by embracing their food and immersing himself in their culture.

Now back in the UK, Keen is already planning his next adventure — a deep dive into the hunter-gatherer lifestyle with a tribe in Ecuador.

The locals came out in droves, shooting off rifles and fireworks and singing traditional songs. Photo: Mike Keen