Last week, Spanish climbers Eneko and Iker Pou announced they had climbed a new route on the south face of Pisco, in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca, with local climber Micher Quito. Only a few hours after we published news of their climb, French climber Herve Thivierge posted comments on the Pous’ social media stating that he had opened the same line 46 years ago.

We contacted Thivierge as well as the Pou brothers to clarify the situation. But both the Pou brothers and Thivierge are sticking to opposite conclusions. Thivierge claims there is no new route, and the Pous insist they climbed a different line that shares only a couple of pitches with the 1978 route.

The debate has highlighted a fascinating topic. The recording of new routes has changed dramatically over the years, particularly with the arrival of the internet.

The Pou brothers announced their route a few hours after they climbed it, with photographs, videos, and a general topo. Herve Thivierge contacted the climbers on their Facebook page and got a quick response from the Basques.

Comments by Herve Thivierge and the Pou brother’s response.

A good memory

“The Pous and Micher Quito climbed the route believing it was a first, but we climbed it 46 years ago, and I have a very good memory of this mountain and this route,” Thivierge told ExplorersWeb. “Of course, the mountain conditions in 1978 and now are different, but the line is still there.”

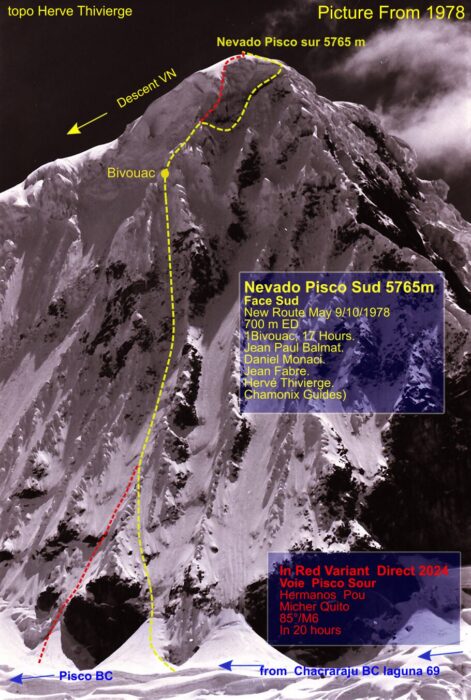

Thivierge provided a new topo of his route and added the sections done by the 2024 team as he understood it.

Herve Thivierge’s version of the pitches, in red, that the 2024 team climbed versus his route, in yellow.

“The Pou brothers made a direct attack variant and a direct exit from our route,” Thivierge said. “Otherwise, they more or less followed our line. It’s hard to believe they only crossed our route once or twice.”

Thivierge noted that the Pou’s 2024 topo does not show any details of their route.

Topos not exact

The Pou brothers strongly disagree.

“No, it’s not the same route, except for maybe a couple of pitches, and even that, I am not so sure of,” Eneko Pou told ExplorersWeb. Pou explained that he drew their topo line on his cellphone with his finger, so it is only approximate. “We will do a new topo as soon as possible.”

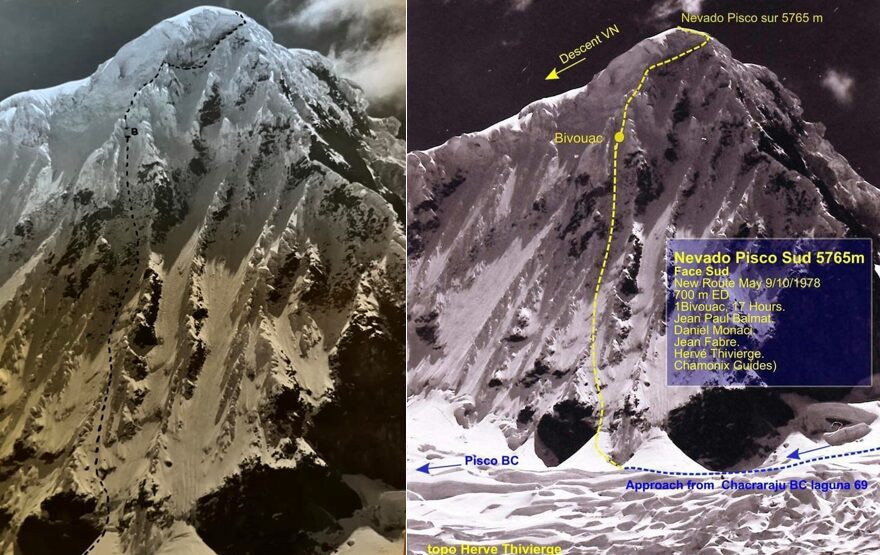

The Pous also note slight differences in Thivierge’s two topos (see the pictures below). In the first topo, on the summit area, it looks like Thivierge’s team moved to the opposite side of the mountain. In the second topo, their route goes along the summit ridge. In one topo, the line goes on top of a buttress above the bivouac point. On the other, the line is further to the right.

Thivierge’s two topos. Differences noted by the Pou brothers are above the bivouac point. Photos and topos: Herve Thivierge

“We have been there, and we don’t believe that ridge can be climbed, in 1978 or 2024, because of snow mushrooms, which are better avoided. Most of the time, they are impassable or, at best, they take too much time and effort to climb,” Eneko Pou said. “On our topo, you’ll see we avoided all the seracs as much as possible and exited directly to the summit. It was a difficult section that took a big effort.”

The upper section of the Pou brother’s route on the south face of Pisco. Photo: Eneko Pou

You can watch a video of how the team climbed that section here:

Few details from old climbs

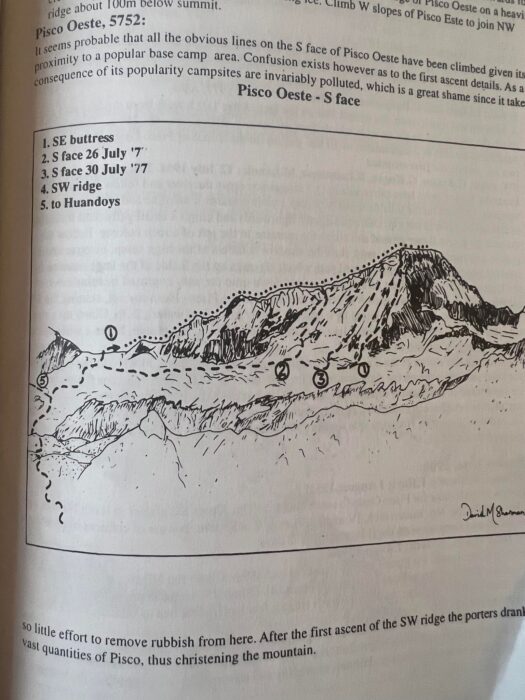

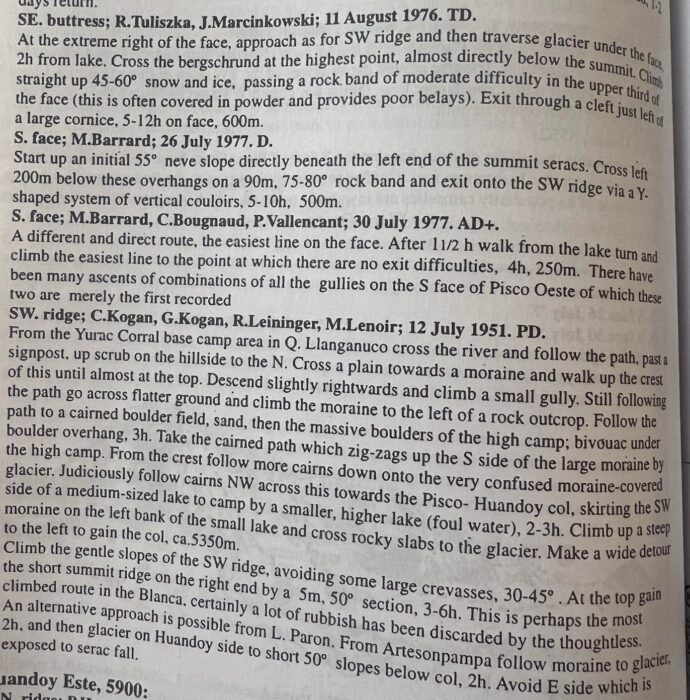

The French team did little to publicize their 1978 climb. In the 1995 guidebook Climbs of the Cordillera Blanca of Peru, author David M. Sharman marks four routes on the south face of Pisco, but the French team’s line is not included.

Pages from Climbs of the Cordillera Blanca of Peru by David M. Sharman, 1995.

“I reported the ascent to the French Alpine Club (CAF) and to the American Alpine Journal (AAJ),” Thivierge told us. Indeed, the report is on the AAJ index (you can find it here), yet it is a very brief description.

“At the time, we did not outline itineraries in photos; we just gave a description. So it is very possible that it did not appear in the 1995 topo guides,” Thivierge explained.

In addition, the highlights of the French team’s 1978 Peru expedition were Taulliraju via the SSW ridge and an attempt on the south face of Chacraraju. Both climbs are on Thivierge’s website, and he said he will add the Pisco route soon.

Climbers who regularly climb in the Cordillera Blanca told ExplorersWeb that it is strange that the Pous would claim a new route on such a popular face without researching previous ascents.

Research

“Of course, we checked for several days,” Eneko Pou told ExplorersWeb while making the trek back from the mountains to Huaraz. “We found no previous routes on our planned line. We never saw the French route marked in a guide.”

The Basque climbers say they checked on the internet, consulted with a local climbing historian, and asked several of the area’s veteran guides.

“It is usually enough, but it is also true that very old lines, before the era of the internet, were often not documented,” Pou said.

Meanwhile, the Pous tend to immediately announce their achievements on social media and send press releases to a pool of specialized media and journalists. They have posted several videos of the climb on Facebook and Instagram.

No newbies

The Pou brothers are professional climbers with decades of experience opening new routes, from sport crags to big walls and also on alpine faces. Thivierge and the team who climbed Pisco in 1978 — Jean-Paul Balmat, Daniel Monaci, and Jean Fabre — are mountain guides from Chamonix. Everyone involved is highly experienced.

So what may have happened? Eneko Pou offers an interesting point: the sheer size of the face might be to blame.

“Perhaps in a topo drawn on a pic of the mountain, the size is misleading. It is a very big face, and in the area where both routes go, there is space for more lines that might not touch each other,” he said. “This is the Andes. If this face were in Chamonix, there would be three or four lines at the same place.”

While this is true for rock and mixed faces, the criteria are not clear for big mountains. On big peaks, climbing lines are not so exact because climbers are looking for the safest routes in changing snow and ice conditions. Expeditions tend to describe their lines by the physical features they pass: couloirs, buttresses, ramps, walls, ridges, etc.

Nevertheless, the Pous insist their line is new. They have spoken with Thivierge and explained their point. “His line goes further to the left, we have climbed some sections that climbers in the 1970s wouldn’t have considered an option.”

Changing conditions

“The mountain has changed radically in the last 40 years. When we check old guidebooks, it’s often hard to identify the routes on the actual mountain,” Eneko Pou explained. “Where the French had a long snow ramp, we had difficult mixed sections in a much drier environment.”

French climbers on the South face of Pisco in 1978. Photo: Herve Thivierge

The first pitch of the climb by the Pou brothers and Micher Quito. Photo: Pou Brothers

“In my experience, looking at all the photos, current conditions are much drier than 50 years ago,” Thivierge agreed. “Currently, it is easier to protect yourself because the rocks appear, and you can place protection, but also sometimes more difficult. When we climbed the South Pisco face in 1978, we climbed virtually without protection. It was very, very steep with inconsistent snow.”

Seracs on Pisco in 1978. Photo: Herve Thivierge

Micher Quito on Pisco this year. Photo: Pou Brothers

Conclusion

“So far, we have opened 19 new alpine routes in Peru and never had this problem before,” Eneko Pou said. “Thivierge and the French climbers accomplished an awesome feat climbing that face in the ’70s. It is something to be proud of, but we are positive our line is different. We also feel we have a right to be happy with the climb we have done.”

Left to right: Eneko Pou, Micher Quito, and Iker Pou on the summit of Pisco. Photo: Pou brothers

The Pous can’t wait to be done with the issue, which they believe benefits no one. “We could have replied in our social media, but we preferred not to stir a nonexistent controversy,” they said.

But Thivierge has not changed his mind. “Sorry to the Pou brothers, who thought they were making a big first,” he said. “This is not the first time that old routes have been climbed again by people who thought they were doing a first ascent.”

Herve Thivierge on Pisco in 1978. Photo: Herve Thivierge