On September 30, 1791, at Vienna’s Theater auf der Wieden, Mozart’s The Magic Flute had its first public performance. The hero of our article was on stage. He was not the 35-year-old Mozart, only two months away from his death. He wasn’t playing the protagonist, nor the Queen of the Night, who was about to give the first public performance of one of opera’s most famous arias.

Our hero was originating the non-singing role of “Slave #1.” His name was Karl Ludwig Giesecke (sort of, more on that later). Though nobody suspected it, in a few years he would be winning scientific acclaim by pioneering the mineralogical exploration of Greenland. Trapped in Greenland for seven years, he won admirers like explorer John Franklin and whaler/naturalist/explorer William Scoresby. But he is still best remembered for The Magic Flute.

Giesecke, right, discovered allanite, left, in Greenland. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Bavarian State Library

Left academia for the stage

Johann Georg Metzler was born in Augsburg, Bavaria, in 1761. Metzler did well enough in school that his teachers advised his father, a local tailor, to send him to university. This he did, and in 1781, he arrived at the University of Goettingen.

He took the opportunity to reinvent himself, abandoning his birth name in favor of Karl Ludwig Giesecke. It isn’t clear why he did this, or where the name came from, except that “Giesecke” was likely a reference to Nikolaus Dietrich Giseke, a German poet.

Giesecke was ostensibly studying law, but his true interests lay elsewhere. He began taking classes in mineralogy and geology. Much more disruptive to his academic career, however, was his love of theater. He spent most of his university career not in Goettingen but in the theatrical circles of Bremen.

By the end of 1783, Giesecke had dropped out of university to join the Grossman Theatrical Company in Frankfurt. The next 16 years of his life are blurry. He kept albums of autographs, a common practice at the time, recording where he was and the people he met, but the album covering much of this period is missing. What we do know is that he was busy, and that he was on the move.

For several years, he toured what is now Germany with various companies, playing minor roles and writing a few of his own comedic opera and opera-adjacent pieces.

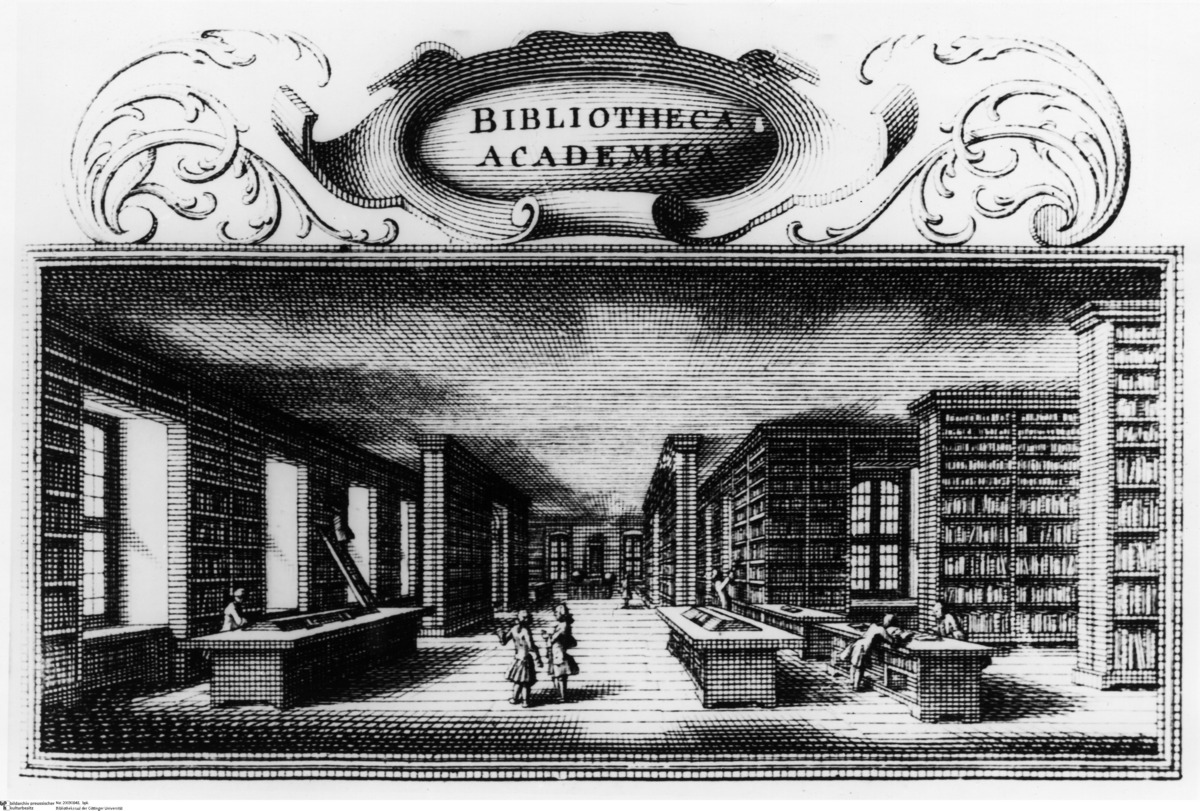

An 18th-century engraving of the library at the University of Goettingen, where Giesecke presumably spent very little time. Photo: Prussian Heritage Image Archive

Left the stage for academia

We’ll rejoin Giesecke in Vienna in 1789, where he was attached to the Freihaus Theater as the company playwright. His first opera for them was a treatment of Oberon, suspiciously similar to an earlier version.

Plagiarism accusations aside, he was also involved in the Vienna Freemason Lodge, where he became acquainted with Mozart. The Schikaneder company had bought out Freihaus and Giesecke with it. So when Emanuel Schikaneder wrote the libretto for, put on, and starred in Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Giesecke was attached, acting as a backup stage manager as well as playing a minor role.

Also in the local Freemason lodge was leading chemist and mineralogist Ignaz von Born. In fact, there were many prominent mineralogists and earth scientists in Giesecke’s lodge. He continued to write plays for Freihaus, but from 1794 onward, he was thinking less about opera and more about minerals. He had a brief spell in the Austrian military, was pensioned out as disabled due to a wound received in Naples, all the while writing.

In 1800, he took another big plunge, leaving Schikaneder and getting a mineral dealer’s license, then hitting the road. The fact that he hadn’t paid rent in a year may have partially influenced his decision to get out of Vienna.

Giesecke passed through much of Western and Central Europe, making his living by collecting and selling minerals. He also attended academic lectures and crafted ambitious plans for the future.

19th century staging design for ‘The Magic Flute’, Act I Scene 6. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The long road to Greenland

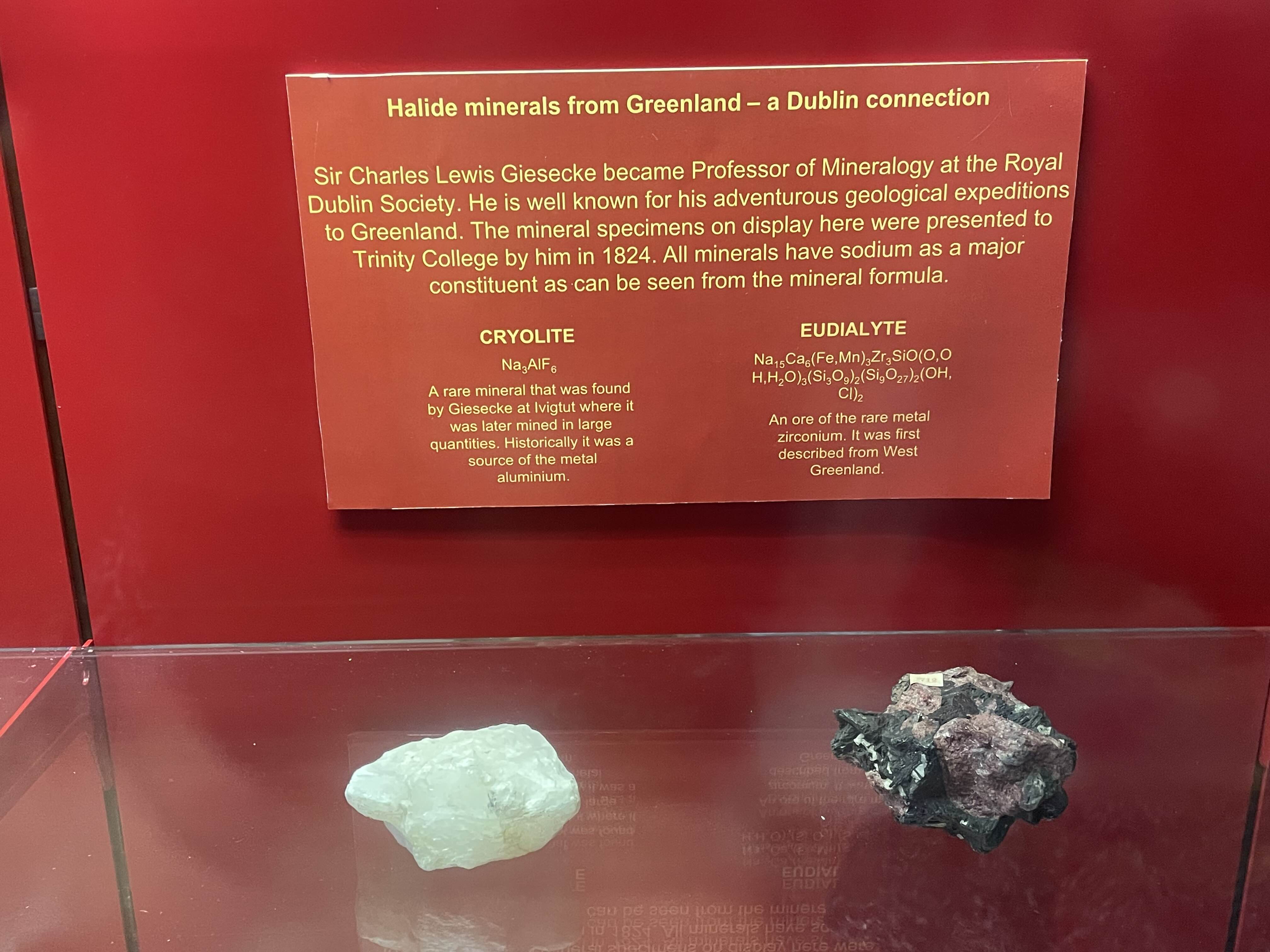

Filtered reports and samples showed that Greenland was rich in rare minerals like cryolite and bornite, but the scientific world still didn’t know where these deposits were, or how extensive. There was work in Greenland for an ambitious mineralogist, and Giesecke wanted in.

But first, in 1805, the Danish government offered to let him gain experience on the Faroe Islands. Giesecke leapt at the chance, while the Royal Greenland and Faroese Trading Commission promised him the help of Faroese officials.

He arrived in early September and made a home base in the humble parish church at Sandagerdi. From there, he set out with great energy, visiting 14 of the 18 islands and collecting a great volume of material. A few years later, in 1807, the English would bombard Copenhagen, and all or most of his Faroese collection was destroyed. This would not be the last time the Napoleonic Wars interfered with Giesecke’s career.

The bombardment of Copenhagen destroyed Giesecke’s collection. Denmark was a neutral country, but Britain captured its fleet to prevent it from breaking the blockade on trade with France. Photo: Statens Museum für Kunst

Giesecke in Greenland

After returning from the Faroe Islands, Giesecke finally got the go-ahead for Greenland. He failed to secure any relevant funding, but the Crown agreed to let him go at his own cost. He wintered in Denmark, then left for Greenland in April of 1806. After a stormy six-week sea journey, Giesecke landed in southwest Greenland at Paamiut, then known as Frederikshaab.

He spent his first few years traversing the west coast of Greenland, mostly via umiak and dogsled. Giesecke seems to have been a true polyglot. He was able to speak Danish by the time he arrived in Greenland, along with German, French, Latin, Hungarian, and Italian. He picked up Greenlandic, also known as Kalaallisut, in fairly short order.

It seems he wasn’t able to interest people in minerals, no matter what language he used, though, and was forced to make many of his forays alone, often on foot. His attention was, characteristically, drawn to other fields of study during his wanderings. His geological passion took a temporary backseat to plant collection, ethnography, mapping projects, meteorology, and archaeology.

He was particularly interested in the abandoned Scandinavian settlements. His efforts constitute some of the earliest efforts to catalogue and map Norse Greenland.

Giesecke was still in Greenland when he got the news about the bombardment of Copenhagen and the capture of the entire Danish fleet. Not only was his collection destroyed, but Denmark no longer had the ships to spare for a mineralogist in Greenland. Effectively, he was stranded.

Both Giesecke’s surviving autograph albums are stored in the National Library of Ireland, for reasons which will become obvious later. I was able to look through them, though not — due to NLI’s photograph policy — post images. The autograph album from Greenland is visibly more damaged than the other. Inside, along with musical notation, watercolor paintings (he was quite good), and silhouette portraits, are quotations and signatures from government officials, scientific minds, and various organization heads.

Inuit items Giesecke brought back from Greenland. Left, a ceremonial women’s anorak. Right, a leather pouch with a hunting scene. Photo: Wellcome Collection

Mysterious Greenland rocks

After over five years of exploring and collecting, the Danish government managed to get an old whaling ship out to pick up Giesecke. The master, Captain Ketelsen, had such a hard time getting through the ice that the ship was quite damaged by the time it arrived. Giesecke looked at the leaky, beaten whaler and decided to take his chances in Greenland. But he packed eight or nine boxes of materials onto the ship, bound for Copenhagen.

The Napoleonic Wars were still raging, and the whaler was promptly captured by a French privateer. This privateer was then taken by a British frigate off the coast of Scotland. You may be gratified to hear that I lost several hours of my life looking through naval records to find more details about the ships involved. But there were so many similar single-ship actions during the era that, without exact details, I came away empty.

At any rate, this anonymous British frigate sent its winnings ashore in Leith. The dockworkers and prize agents were evidently not mineralogists, because they dumped the valuable boxes of samples in a warehouse and let them sit there until 1813.

That was when Thomas Allan, banker and mineralogist, found them. He spotted what looked to be rare and valuable materials among the weather-worn pile. With the help of the chemist Thomas Thompson, he identified minerals like cryolite, sodalite, garnets, and a new mineral they called allanite. He had paid £40 for a collection easily worth £5000 in cryolite alone. (That’s almost $700,000 today.)

A Royal Navy vessel captures a French privateer. This is actually a brig, not a frigate, a distinction which matters a great deal to a very small subset of people. Photo: Royal Museums Greenwich

Still in Greenland

Meanwhile, Giesecke was still in Greenland. He had turned 50 in the Arctic, still disabled by the wound he received in Naples, but he attacked his collecting and exploration with typical dogged energy. Discovering that not only had his Faroese collection been destroyed, but that his Greenland samples were lost only spurred him on.

Giesecke often went on 60km+ treks alone on foot, carrying back heavy rocks while dodging crevasses and navigating the Inland Ice. In one alarming incident, he reported that he was alone when he stumbled upon the bodies of fifty Russian fur hunters, killed in an avalanche.

The latter years of his Greenlandic period were harder than the earlier ones. He pushed further north, facing more punishing conditions as he passed 76 degrees north. Working with local Inuit and Moravian missionaries, he took detailed meteorological records. These show his last few years were notably colder than the preceding ones. Nevertheless, Giesecke found large deposits of coal and cryolite.

Finally, in the summer of 1813, Giesecke heard that a whaler from Hull had landed to take on water. He shipped himself and his collections on the George and Thomas, ending his seven-and-a-half-year stay in Greenland.

Two mineral samples collected by Giesecke, now in Trinity College Dublin’s Geology museum collection. Photo: Author

Off to Edinburgh

When he landed in Hull that August, he caused a minor stir at the docks by disembarking in full Greenlandic furs. His European-style clothes had long since disintegrated. Hoping to reclaim, or at least locate, his first set of samples, Giesecke wasted no time in making for Edinburgh. It was no good; under maritime law, the samples were prize cargo, and their sale was both legal and final.

Edinburgh was, however, a scientific mecca at the time. As the broader scientific community learned of Giesecke’s years of work and his two great losses, he won a great deal of sympathy and attention. Soon, Giesecke’s album bore an inscription from leading scientist and fellow freemason Sir George Mackenzie. Mackenzie, in turn, knew Thomas Allan, who seemed to be a bit sheepish regarding his windfall.

Allan invited Giesecke to stay in his home in Edinburgh while he figured out where to go next. It was also Allan who wrote Giesecke a letter of recommendation to the Royal Dublin Society. They were looking for a professor of mineralogy. The Society’s own vice-president, Baron Foster, wrote his other letter, where he emphasized how liked and respected Giescke was in Edinburgh, how valuable his collection was, and that he also, importantly, had “gentleman-like” manners. It led to a prestigious professorship in Dublin, despite the fact that Giesecke did not speak English.

Within weeks of arriving in Scotland, Giesecke had thus gone from an unemployed and unknown mineral collector to a well-respected scientific figure. He made a grand lecture tour of Europe before arriving in Ireland to take up his position, where he underwent one final reinvention. He lectured as Sir Charles Lewis Giesecke (Denmark had knighted him).

Thomas Allan. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Life in Ireland

It took Giesecke 16 months to become fluent in English, and he was soon a popular lecturer. Under his auspices, their museum collection grew to over 30,000 catalogued mineral specimens, from Greenland, from his connections and trading, and from his subsequent travels in Ireland. He also donated the polar bear skin he’d slept in for seven years, though it turned out to be infested with moths, which soon ravaged all the furs and taxidermy of the entire museum.

In 1818-19, Giesecke took a final grand tour of Europe, hobnobbing with the scientific crowd and reconnecting with the theatrical scene. He struck up an acquaintance with, of all people, the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Goethe was a passionate amateur scientist and was interested in mineralogy. The pair exchanged letters and traded mineral specimens for several years.

Gisecke’s experience exploring and wintering in the Arctic attracted the attention of several explorers. William Scoresby Jr. and Sr. consulted Giesecke, with Jr. using his chart of the Western Greenlandic coast on his 1822 expedition. The famously doomed John Franklin likewise drew on Giesecke’s experiences when preparing for his early overland expedition.

Giesecke became vice president of the Royal Irish Academy and undertook geological expeditions in the counties of Donegal, Mayo, Antrim, and Galway. He was still lecturing and collecting into his seventies, as a persistent chest complaint he called “Arctic cough” began to trouble him more and more. In March of 1833, he died of this pneumonic complaint in the middle of a dinner party, and was buried in St George’s Church, Dublin. Ironically, it later became a theater.

The topaz that Giesecke collected in Northern Ireland. Giesecke’s Royal Irish Society Museum eventually became the National Museum of Ireland. Photo: National Museum of Ireland

But did he write The Magic Flute?

Even with his success and busy life in Ireland, Giesecke never forgot the theater. It was at a dinner party in Vienna in 1818 that he allegedly made a startling claim. The author of the libretto for Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Giesecke said, was mainly himself, not, as advertised, Emanuel Schikaneder.

Giesecke himself didn’t publicize his claim. It was only in 1849 that the first account of this dinner party and the attached claim was published. Since the mid-19th century, debate has raged, in a quiet, niche academic way, regarding who wrote the libretto for Mozart’s last opera.

Pro-Gieseckites cite the frequency with which passages from the opera are quoted by fellow scientists in Giesecke’s autograph books. These include a line from Act 1, Scene 17, reading “Glück auf Erde,” a common greeting among geologists which literally wishes one a safe return to the surface. There are also apparent similarities between lines in Giesecke’s earlier works and lines from The Magic Flute.

That he wrote the libretto himself and Schikaneder took the credit seems a bit of a stretch, based on the evidence. But it is wholly possible that, as staff writer for the company and stage manager for much of its run, Giesecke contributed in some way to the libretto. If he did write any of The Magic Flute, as historian Alfred Whittaker points out in a 2007 article, then Giesecke’s words have been heard more than those of any other scientist.