In 2017, the U.S. government filed a lawsuit with the curious title of the United States of America vs. Approximately Four Hundred Fifty Ancient Cuneiform Tablets; and Approximately Three Thousand Ancient Clay Bullae.

Although it is tempting to envision a world in which these tablets and bullae (an ancient document seal) were themselves on trial for, say, manslaughter, the case concerned looting and smuggling of Iraqi antiquities.

Many of the accused tablets and bullae described life in the ancient city of Irisaĝrig. A center of religious life and commerce, it thrived at the end of the 3rd millennium BCE. During the Iraq War, looters pillaged its ruins and flooded the antiquities market with them.

But although looters may have found Irisaĝrig, archaeologists still haven’t.

Worth conquering

Irisaĝrig was a big enough city to be worth conquering, but not big enough to do the conquering. In the last centuries of the third millennium BCE, it paid tribute to the Akkadian Empire, then the Third Dynasty of Ur, and then the nearby city-state of Malkum. Like other regional cities of that time, Irisaĝrig bred sheep and cattle, grew barley, and traded with other settlements via a complex network of roads and canals.

Remnants of these grander, more aggressive civilizations lie scattered among Irisaĝrig’s artifacts. Most of the tablets deal with mercantile affairs in the Akkadian or Malkum Empires. Other records ascribe Irisaĝrig’s temples to legendary rulers of Ur, now revered as gods.

The dominant religious figure in Irisaĝrig and its nearby sister city of Kesh was Ninhursaĝ, a Sumerian mother goddess of fertility and mountains. The most famous temple to Ninhursaĝ stood in Kesh, and the residents of Irisaĝrig made frequent trips there. In their own home city, they carved a 30-kilometer canal connecting them to the Tigris River. They called it Tabbi-Mama, or “Mama-Has-Called,” a reference to Ninhursaĝ.

Hobby Lobby

Archaeologists now have thousands of tablets from Irisaĝrig, but they didn’t obtain them from excavations. Instead, they came from the best place to get ancient Sumerian artifacts: Hobby Lobby.

Hobby Lobby is a U.S. crafts store chain best known for its great coupon discounts and the glitzy Evangelical books on sale at the checkout. Urban legends abound that Hobby Lobby refuses to use barcodes because they’re the mark of the Beast (probably untrue), that they don’t cover birth control in their employee health plan (verifiably true), and that they smuggled antiquities into the U.S. to stock their Bible museum.

In 2011, U.S. customs officials seized a shipment of ceramic tile samples headed from Turkey and Israel to Hobby Lobby’s offices in Oklahoma. The boxes did indeed contain ceramic tile samples, although they happened to be inscribed with 4,000-year-old records of Irisaĝrig. And despite the postage marking, they had been shipped to Oklahoma from the United Arab Emirates, a notorious hub of black market art deals.

Looters’ holes at Yasin Tepe in Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin (Wikimedia Commons)

Looters found Irisaĝrig during the Iraq War

Hobby Lobby and the family that controls it had tangled with archaeological controversy before. Their Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., has been accused of proselytizing at the expense of accuracy. Their prized collection of Dead Sea Scrolls had faced accusations of forgery. (Indeed, all turned out to be fakes.)

But the new court case, filed in 2017, blew these controversies out of the water. The U.S. government alleged that Hobby Lobby had used the chaos of the Iraq War to purchase stolen antiquities. In 2010, a cultural artifacts expert had warned them that any Iraqi items they purchased from the UAE were likely to have been looted. They spent $1.6 million on a massive cache anyway, according to trial documents. At the end of the trial, Hobby Lobby admitted fault and accepted a civil fine, but no individuals were convicted of a crime.

Looted goods from Iraq had flooded the antiquities market in the 2000s and 2010s. When the U.S. invaded an Iraq already suffering under Saddam Hussein’s rule, professional looters saw the perfect distraction, and everyday citizens saw an opportunity to protect themselves economically. There was one thing about Iraq that the West loved: its past. So in 2003, looters ransacked the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, stealing thousands of priceless artifacts and selling them on the black market. The looters included teams of professional thieves and opportunists alike.

They didn’t stop at the museum. Holes blossomed in the ground at archaeological sites. Thieves took anything that looked old and valuable and passed it on to dealers. Some of those thieves found Irisaĝrig. Some of those dealers found those thieves. Hobby Lobby found those dealers.

U.S. Customs found Hobby Lobby guilty and repatriated almost 4,000 tablets back to Iraq. On those tablets were clues to the location of Irisaĝrig.

Archaeologists on the hunt

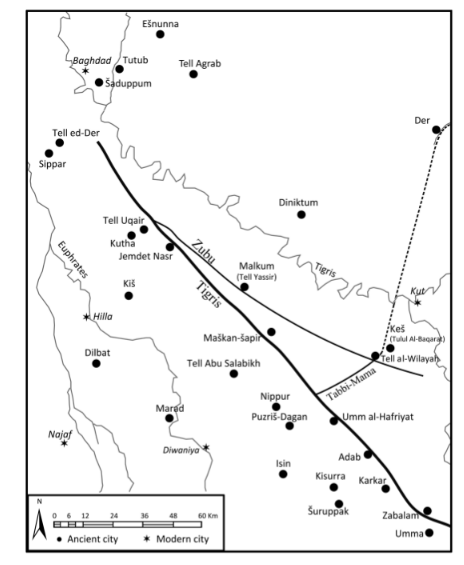

A map showing the location of known ruins in the vicinity of Irisagrig. Photo: Steinkeller 2022

Despite the flood of Irisaĝrig artifacts that hit the antiquities market in the decade after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, no one in the legal antiquities sphere actually knows their provenance. Unsurprisingly, no looters have come forward. It is up to archaeologists to piece together where Irisaĝrig is, and find it before it’s looted beyond repair.

It’s harder than it seems to find a specific ancient city in the hills of Iraq. They have rather a lot of them. To trace Irisaĝrig, Assyrian specialists rely on detailed trade records, especially those from the Third Dynasty of Ur. Many of the tablets recovered from the black market over the last decade date to the Third Dynasty.

Clues to the location of Irisaĝrig include:

- It was on or near the banks of the Tigris.

- It was near the city of Kesh.

- It lay on the Tabbi-Mama canal.

- It took boat-towers four days to travel from the major city of Umma upstream to Irisaĝrig.

- Travelers from Irisaĝrig to the city of Der began their journey by boat.

But the banks of the Tigris are so dotted with ruins that half a dozen sites could plausibly fulfill the geographic criteria. Academic debate remains intense. Much of it revolves around canal flow directions. For instance, it took two days to travel along the Tabbi-Mama canal from the Tigris to Irisaĝrig. But was that a short distance upstream or a longer distance downstream?

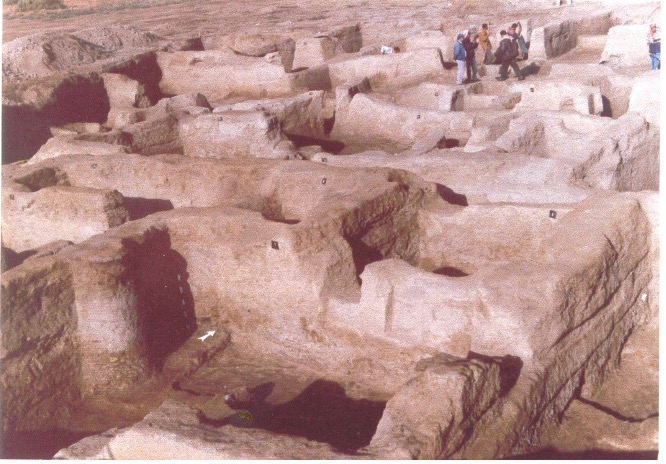

The excavation of Tell al-Wilayah in 2002. Photo: SBAH/Tell al-Wilayah Excavation

Tell al-Wilayah, the most famous candidate

Wikipedia insists that Irisaĝrig’s location is practically settled. It lies, says the online encyclopedia, at an archaeological site known as Tell al-Wilayah, 31km from the banks of the Tigris.

Tell al-Wilayah has a lot going for it. It lies at the weir of a canal; it’s a plausible four-day journey from Umma, and it covers an entire 64 hectares, larger than most other ruins in the area. Crucially, it sits right next to Kesh, whose location is known.

But in addition to perpetual academic squabbling over canal flow directions, one particular clue raises doubts about identifying Tell al-Wilayah with Irisaĝrig. Three separate sources describe travelers leaving Irisaĝrig to travel by boat to Der. There is no waterway connecting Tell al-Wilayah and Der. The only path between the two is on foot over the desert.

Finding conclusive evidence in either direction poses challenges. Looters ransacked Tell al-Wilayah during the war, limiting the evidence available at the site.

But old collections may still hold clues. In 2002, the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities collected about a hundred artifacts from Tell al-Wilayah, including cuneiform tablets. Then the U.S. invaded. Iraq thrashed in post-war chaos. In 2014, ISIS invaded.

Three years later, the Iraqi government finally declared victory over ISIS, in large part through help from Kurdish Peshmerga fighters. Then, with perfect timing, came COVID-19.

Throughout all of this, the artifacts from the 2002 Tell al-Wilayah excavation endured, their secrets unpublished.

But despite everything, things are looking up for Tell al-Wilayah and its neighboring ruins. Governments around the world continue to find artifacts looted during the war and repatriate them to Iraq. A joint collaboration between Iraqi, American, British, and Polish universities launched in 2025 to study the 2002 Tell al-Wilayah artifacts. And in Wasit Province, where the site lies, the government recently announced an initiative to fund archaeological preservation. They hope to obtain UNESCO World Heritage status for sites like Tell al-Wilayah and attract tourists to the region.

Wherever the ruins of Irisaĝrig lie, the world is getting a little bit brighter.

Archaeologists for the new project pose at Tell al-Wilayah with the Director of Antiquities for Wasit Province during a 2025 visit. Photo: Tell al-Wilayah Project