On a typically balmy mid-September day in southern Arizona in 1924, WWI veteran Charles E. Manier took his family for a drive. Manier, along with his wife, son, and father, enjoyed a picnic at nearby Picture Rock. Now they were driving back along Silverbell Road.

Many of the homes in the U.S. Southwest are built from adobe, a sort of mudbrick which keeps buildings cool during the day and warm at night. These homes were plastered with lime, leaving old lime kilns scattered across the landscape. Entertainment was hard to come by in 1924, so when they passed an abandoned lime kiln, the family pulled over to have a poke around.

Charles noticed something strange poking out of the ground. A flattish, metal object was stuck in the hard caliche (soil cemented together by lime into a hard concretion). Intrigued, Manier fetched an old pick and began working to free the object.

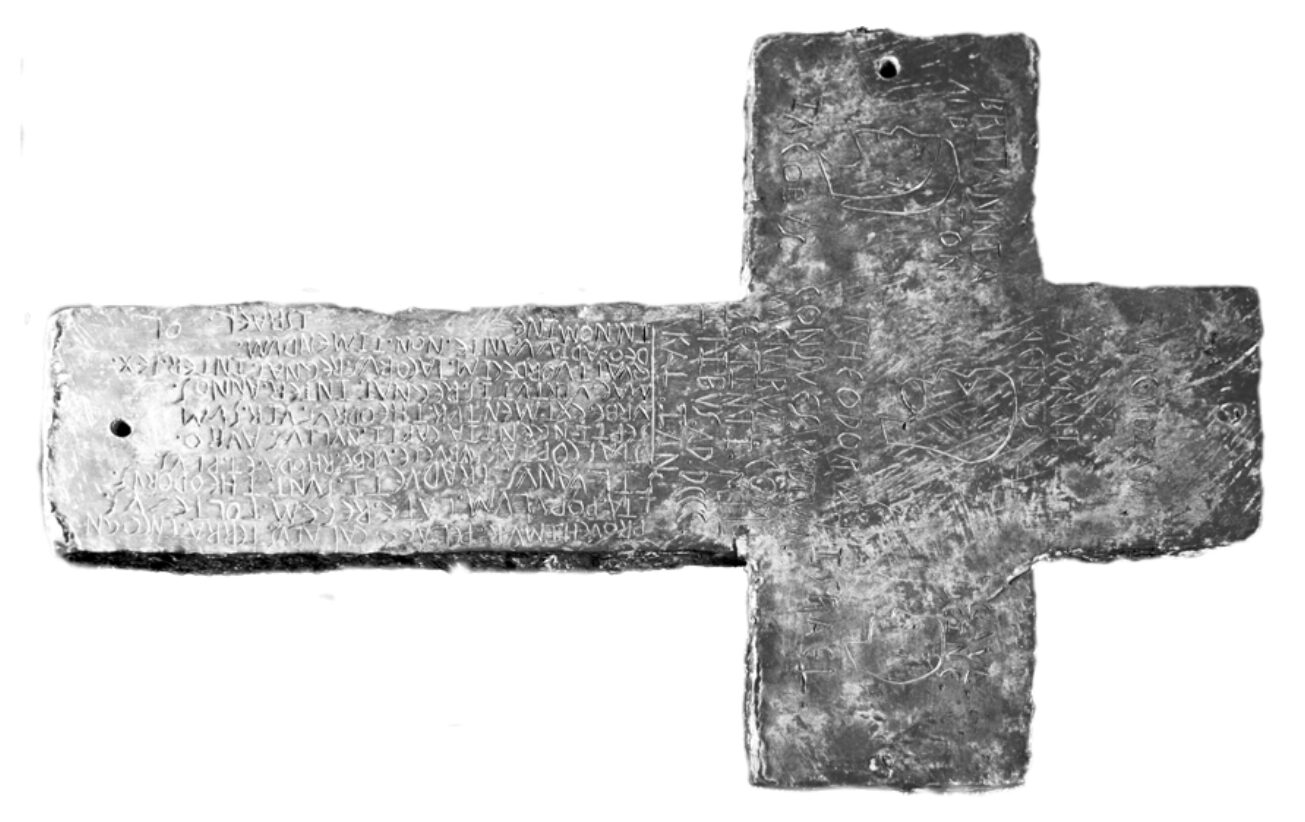

As the caliche was chipped away, a 46-centimeter-long lead cross emerged. But the real mystery was only revealed later, when Manier, having lugged the 30-kilogram cross home, washed it clean. Free of dirt, Manier was able to see the inscriptions. They were in Latin — and they included a date: 790 AD.

One of the two lead crosses, riveted together, which Charles Manier found on Sept. 13, 1924. Photo: Arizona Historical Society Museum

Unearthing the ‘Tucson Artifacts’

Manier was intrigued, to say the least. He enlisted a friend, a lawyer named Thomas Bent, and together they returned to the old kiln site. They found more artifacts, not just crosses but swords and spearheads.

Thomas Bent went all-in on his friend’s find. Discovering that the old kiln site land was unowned, he quickly purchased it. Together, with the assistance of several academics from the nearby University of Arizona (my alma mater doesn’t come off particularly well in this story, I fear), they set to excavating.

Over the following months, they continued to unearth strange lead artifacts, from more cross tablets to weapons to religious symbols.

In 800 CE, on this patch of desert out by Sunset and Silverbell, a Roman settlement didn’t stand. Photo by my father, who braved snakes and 41˚C weather to photograph a patch of scrub for me.

Early debate

Manier and Bent had contacted the nearby university — the University of Arizona– after the first cross was discovered. A local paper, the Arizona Daily Star, reported on the find. The first academic to examine the cross was Frank Hamilton Fowler, the head (and sole member) of the Classics department.

He found the inscriptions unconvincing, with poor Latin, and expressed his opinion that the oldest the items could be was 900 years old. There was also the use of “AD” for Anno Domini, not in common use until the 11th century.

Enter Andrew Ellicott Douglass, astronomer and inventor of dendrochronology (tree-ring dating). Also at the U of A in 1924, he was intrigued. He started reaching out to experts, including the British Museum.

They replied haughtily, “We all find it difficult to believe that the cross can be anything but the work of a person living not very long ago, and desirous of mystifying other persons.” A.E. Douglass was unconvinced by this reasoning.

Then geologist Clifton J. Sarle joined the merry band of Tucson Artifact Believers. Caliche, they noted, doesn’t form overnight, and many of the artifacts were over a meter below the surface.

The final prominent member of the “pro-artifact” team was a local art teacher and passionate historian named Laura Coleman Ostrander. Approached by Bent, she took up the challenge of translating and interpreting their finds. For over a year, she pieced together the Latin and Hebrew transcriptions, using them to construct a history of Arizona’s lost Roman-Jewish kingdom.

A.E. Douglass with the original Steward Observatory telescope. Photo: University of Arizona Library Special Collections

Calalus, the unknown land

In the year 775, her interpretation went, a Roman-Jewish expedition went across the sea to the west coast of North America. They called their landing place “Roman Calalus, an unknown land.”

Led by their king, Theodorus, the newcomers soon encountered the Toltezus, a group of people already living in Calalus, who soon became their bitter enemies. In addition to chronicling the list of kings, the rest of the “historical account”-type tablets deal with the Roman Calalus-Toltezus wars.

During his 14-year reign, Theodorus proved himself a brave warrior-king, who “carried on much warfare with the Toltezus.” After Theodorus, King Jacobus ruled Calalus, and he rebuilt the city which the Toltezus had sacked late in the reign of his predecessor. After him came Israel I, who ruled for an impressive 67 years. His successor, Israel II, ascended the throne aged only 26, and was killed in battle against the Toltezus six years later.

But the reign of Israel III proved disastrous. As the unnamed chronicler records: “[In] 880 AD, Israel the 3rd was banished since he had liberated the Toltezus. He first broke the custom. The earth trembled. Fear overwhelmed the hearts of mortals in the third year after he fled. They betook themselves within the city and kept themselves within the walls.”

The historian writes that 3,000 were killed during this last, terrible outbreak of fighting. The capital city was under siege, and things appear grim: “it is uncertain,” our narrator finishes, “how long life will continue.”

The record seems to end there, with the Romans of Calalus wiped out by the Toltezus, leaving only one collection of a few dozen artifacts.

This cross was elaborately carved with conflicting religious symbolism. Photo: ‘Photo of Lead Cross at Site’ by Erin, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Who were the Toltezus?

In the minds of many, the inclusion of the Toltezus people was a huge score on the side of authenticity. Toltezus could very convincingly be read as a Latinization of the Nahuatl word Tōltēkah, meaning “the people from Tollan.” This is where we get the English term “Toltec,” referring to a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican people.

Believers argued that the seemingly clear reference to a real people from ancient times was too perfect a detail for a fraud to have invented it.

There are some points that don’t quite add up here — Toltec influence did not extend so far north, and they didn’t reach prominence until around 900. If the Toltecs had been in the area, why were there no Toltec artifacts? Where was the city of Rhoda, where Theodorus brought up his forces, and where 700 were captured?

That is the central problem with the Tucson Artifacts’ believability. Even if the artifacts themselves were perfectly accurate (and they aren’t; we’ll get to that), the question remains: Where is everything else?

Many buildings built in the Early Medieval era in the Mediterranean survive to this day. Did these Arizona Romans step off the boat and forget what mortar and bricks were? Looking back, it seems obvious. But in the excitement of the moment, even respected historians and archaeologists were taken in by the Tucson Artifacts.

The Toltecs were great builders, erecting edifices like the Temple of Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli in their capital city of Tula. I guess they just didn’t feel like building in Arizona, though. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Battle in the press

For over a year after the first find, the papers remained silent on the subject of Arizona’s Roman artifacts. U of A scholars remained divided. When A.E. Douglass’s absent boss, Byron Cummings, returned from Mexico, he was met with the problem of the artifacts.

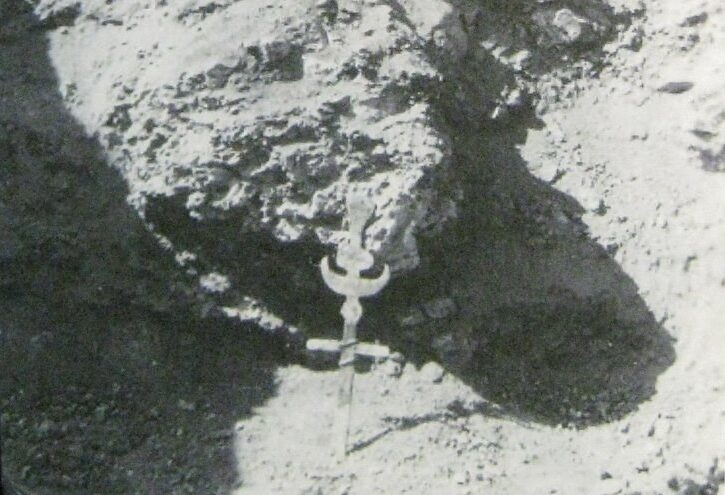

He visited the site to help excavate a sword blade, and afterwards released a statement to the press. The object’s position in the undisturbed caliche seemed irrefutable. “I am convinced that they are genuine,” Cummings announced.

After this statement, newspapers all over the country picked up the story, including The New York Times, which gave it a front-page spot. They presented the claims of the Arizona-based scientists regarding the caliche. But they also dedicated a lengthy section to Dr. Bashford Dean, then Curator of Arms and Armor of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a specialist in forgeries.

“The Arizona specimens are modern forgeries, probably local, and certainly without either interest or value,” Dean told them.

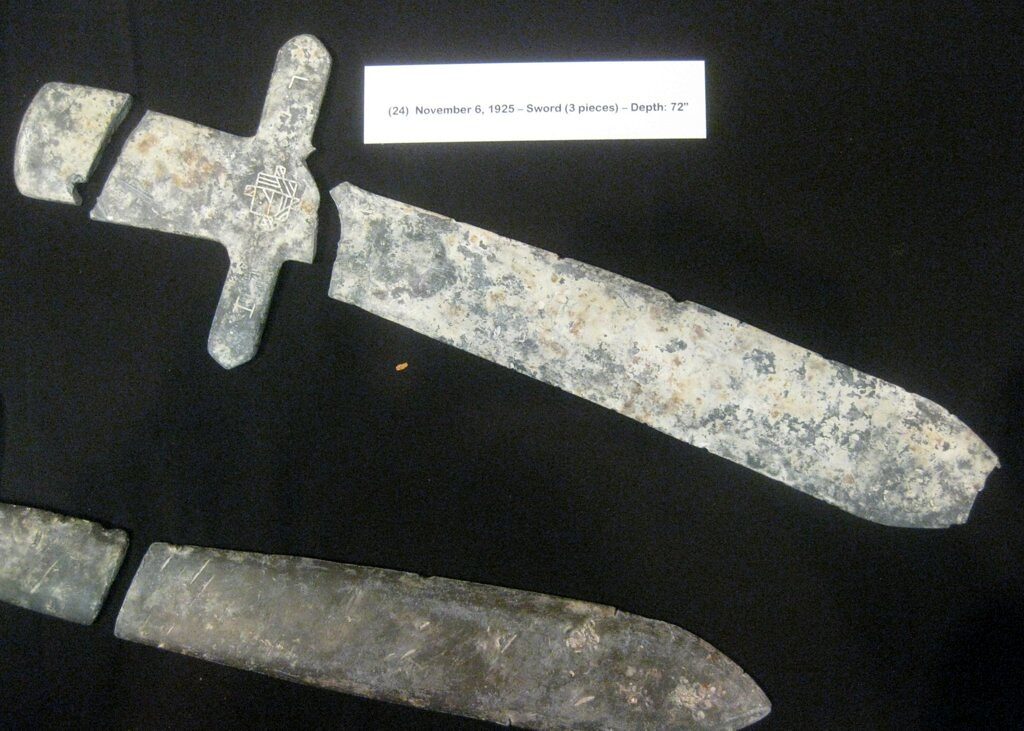

As evidence, he pointed to the fresh instrument marks which had been deliberately rounded in a few places to give the appearance of age.

The figures, he continued, were crude copies of work the artist had seen, and the crowns and swords were childish imaginings, rather than accurate depictions of items from the period. There was also a very basic Latin mistake; “Gaul,” the English form, is written instead of the correct Gallia.

There was a flurry of articles from the Arizona Daily Star, with titles like, If Cummings Says They’re Genuine, They are, Declare Tucsonans. But they didn’t speak for everyone. Another local paper, the Tucson Citizen, had been doing some digging.

One of the lead objects resembles a spearhead. Note that it bears marks which seem to have been made with a file. Photo: Don Burgess

Timotio Odohui

In January of 1926, the Tucson Citizen began publishing a series of articles. A retired cowboy named Leandro Ruiz remembered “a highly educated young Mexican, a sculptor, who lived at the lime kiln with his parents in 1886.”

The Citizen latched onto the lead. They discovered that the man’s name was Timotio Odohui, and he had possessed a large library of Hebrew and Latin classical texts. Ruiz further remembered that Odohui had made lead-cast objects, including a marker to indicate where Ruiz had once fallen from a horse.

Another elderly local had confirmed Ruiz’s account, recalling both the Odohui family and their son’s felicity with lead sculpting. The Times was quick to pick up the story. Timotio’s father, Vicenti Odohui, had been forced to leave Mexico with his family due to political instability following the Franco-Mexican War.

An educated man, he’d brought the family library with him, containing a collection of classical works, heirlooms up to 200 years old. For eight or nine years, the family burnt lime in the kiln. But after Vicenti died, his wife and son disappeared, presumably returned to Mexico.

Dean argued that the swords were imperfect copies of a drawing of Roman swords. Photo: ‘Two Lead Swords’ by Erin, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The final coffin nail?

If Odohui was the creator of the Tucson Artifacts, that would explain why the Toltecs, a civilization centered around Hidalgo, appear in the American Southwest.

It would also explain why, as Frank Fowler discovered, every phrase of the inscriptions can be found word for word in one of three dictionaries, all first published after 1864. The Latin and Hebrew writing was copied in chunks, almost verbatim, from phrasebooks, reassembled like puzzle pieces to tell an alternate history.

Cummings, for his part, was unconvinced.

“I am firmer than ever in my belief that they are genuine,” he told the Citizen.

In fact, he argued, the whole story was implausible. “Where did this Mexican boy obtain his reported wonderful university education? There were no universities in Mexico those days.”

The first university in Mexico was established in 1551, for the record. But though the Odohui theory, and Fowler’s discovery, seemed to doom Cummings’ favorite finds, he still had one ace up his sleeve.

The caliche issue

“I am not able to refute Dr. Fowler’s citations and references,” he admits, “but how can it be possible that the crosses were inscribed within the past 20 years, when we have positive proof that the relics have been buried in the caliche formation for at least 50, 100, or a longer term of years?”

But the caliche is a double-edged sword. See, they were buried, seemingly, too deep to be recent. They were also buried too deeply to be from 800 BCE. So, how could the caliche be explained?

James Quinlan, a Tucson geologist, undertook a survey of the site to find the answer. In his 2000 report, which he shared with historian of the Southwest Don Burgess, he explained how a recent object could appear to be embedded deeply in caliche. Most of the objects had been found on the edge of embankments, in the softer “horizon” of the caliche.

Then there was the other claim that believers had made: that caliche could not be artificially created. Quinlan decided to test it out. He mixed sand, gravel, and store-bought lime, stuck a lead pipe in, and waited. It quickly dried, and the rod appeared completely encrusted in caliche.

Caliche, also called calcrete, is laid down over time. Things trapped in the lower layers are old, and inclusions above them are more recent. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

So who did it?

Besides the attribution to Timotio Odohui, speculators have proposed various alternate theories throughout the years. Perhaps, for instance, the artifacts were left by Spanish conquistadores or missionaries in the 16th century.

In a 2010 interview with the Arizona Daily Star, Don Burgess, then president of the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society, expressed his own theory: that the artifacts were being made at the same time they were being discovered.

Quinlan agreed. In his report, he pointed out that the later objects could have been planted in the emerging excavation trenches, so they appeared to be deeply embedded. He concluded that he “would suspect someone close to the project.”

Again, the Latin dictionary quotations may be the smoking gun. These three books were Harkness’s Latin Grammar, published in 1881, Allen and Greenough’s Latin Grammar, from 1903, and Roufs Standard Dictionary of Facts, 1914. The kicker: the 1903 edition of Allen & Greenough’s Latin Grammar was the Latin textbook used in Tucson, Arizona high schools in 1924.

We don’t know for certain who made the artifacts. Bent and Manier are rarely fingered as the culprits. Rather, AE Douglass, Clifton Sarle, and Laura Ostrander are the usual alternative suspects to Timotio Odohui. Perhaps Sarle, whom the University of Arizona had recently fired, and Ostrander, cut out of the academia she longed to be part of, wanted to pull one over on the scholars. Maybe a joke got really out of hand.

Downtown Tucson in the 1920s. Photo: Arizona Pioneer Historical Society

Legacy of the Tucson Artifacts

After the initial dust settled, excavations continued for a few years. They finally uncovered all 32 artifacts: 31 lead, one carved caliche block. But the world of serious archaeology has left them behind.

Nevertheless, over a century on, there are still believers. Certain archaeological (or pseudo-archaeological) circles are eager to find evidence that changes the timeline of European settlement in the Americas.

In 2013, that bastion of credibility, the History Channel, ran an episode of America Unearthed on the Tucson Artifacts. Their conclusion was that they were probably real and probably related to a Masonic and/or Templar conspiracy.

By the way, I didn’t mention it earlier, but I think now is the funniest time to bring up the fact that one of the crosses has a drawing of a dinosaur.

Today, most of them are kept in the collection of Tucson’s Arizona History Museum. In 1996, journalist Peter Gilstrap, working on an article for the Phoenix New Times, visited the basement of the Arizona Historical Society to see the relics. Since their arrival in 1994, no one else had asked to see them.

The artifacts, abandoned by historians due to being fake, have been left to the crackpots and cranks. Even among that crowd, they aren’t very popular.

In a way, this is a pity. Gilstrap’s article included an interview with University of Arizona archaeologist Peter Steere, who had recently lectured on the Tucson Artifacts.

“They’re a part of the local folklore,” Steere said. “A part of archaeology folklore, and a part of the history of southern Arizona.”