Pietro Querini sailed from Crete in 1431, bound for Flanders with a crew of 67. Almost two years later, he and 10 other survivors limped back home, returning not from Belgium but from a remote Norwegian island inside the Arctic Circle.

They had survived a powerful storm which wrecked their ship, a long journey in an open boat across the Atlantic, and months alone on an uninhabited, frozen island. Found only by chance, first-hand accounts by Querini and his men record their desperate struggle against starvation and the elements.

Their leader, Pietro Querini

Pietro was born around the turn of the 15th century into two powerful old patrician families, the Querini family and the Morosini, through his mother, Daria. In 1422, after he had turned 18, his father enrolled him in the Balla d’Oro, a lottery in which the sons of young noblemen had a chance to enter the Venetian ruling council before reaching the minimum age of 25. This shows the privilege and power that Querini was born into.

He was, however, unlucky and was not one of the boys selected. Less than a decade later, his father died and left his land holdings to Pietro, who was his eldest son. These holdings included the fiefs of Castel di Temisi and Dafnes, on Crete.

Since the early 13th century, Crete had been a Venetian colony, with waves of revolts and civil wars. At the moment, however, the island was peaceful and prosperous. In short, it was a convenient time to inherit part of it, and Querini set out to make the most of his inheritance.

Once on Crete, he acquired a ship, the Querina, and invested much of his personal fortune in equipping and loading her with valuable trade goods. Though a single-masted cog, the Querina was a large ship with a generous hold, filled to the brim with 700 barrels of Malvoisie wine, as well as pepper, ginger, olive oil, and cotton. If they reached the bustling markets in Flanders, the voyage would be incredibly profitable.

A 15th-century Venetian cog. Photo: Museo Galileo

An inauspicious beginning

Only days before they were set to sail, Querini’s young son died suddenly. It seemed, he wrote, that “God had turned His back on me.” But the ship was all loaded and ready to leave. Despite his grief and what he recognized as a terrible omen, Querini set sail on November 5, 1431.

Misfortune continued to follow the ship, as it ran into shoals in the harbor of Cadiz. It had to be completely unloaded, dry-docked, repaired, and reloaded. While in Cadiz, Querini learned that they, the Venetians, were now at war with the Genoese. Again gritting his teeth and carrying on, Querini took on a host of soldiers in anticipation of running into conflict. The repaired ship and its now 112-strong crew set off in mid-July.

Possibly hoping to avoid Genoese adversaries, Querini diverted far south of his planned course but eventually reached Lisbon, low on food and suffering in the heat. They took on more supplies, repaired the ship again, and set off for the final stage of their journey to Flanders. Perhaps trying to turn his luck around, Querini made a quick stop in Galicia to visit a famous pilgrimage site.

It did not, it seems, have the desired effect. They were at the very mouth of the English Channel, rounding Cape Finisterre in early November, when a storm hit.

The medieval ‘Road to Santiago’ ended here, at the Catedral de Santiago de Compostela. Querini visited with 13 fellow shipmates. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The wreck

Their damaged rudder gave way almost immediately. Fierce winds seized the ship, and they were helpless to avoid being driven before the storm. The Querina’s sails were torn to shreds as she raced involuntarily northward, despite the pair of sea-anchors the crew threw out behind to slow her down.

Unable to move with the waves, she began shipping heavy seas. By November 21, the crew had to bail constantly. They had no way to steer the ship, and still the wind blew, and waves flooded the deck. On November 27, they found themselves in only 80 fathoms (around 146 meters) of water and attempted to anchor. It held for about a day before panicked crew members, fearing the structural strain that anchoring put on their already weak ship, cut the ropes. They were now adrift without anchor, sail, or rudder.

Despair was, understandably, the prevailing feeling aboard. The final blow came in the wee hours of December 8, when a massive wave from leeward turned the ship onto its side, flooding it with seawater. They tried to bail, throwing everything they could think of over the side to lighten the ship, including the masts. Finally, Querini gathered the crew and announced that it was time to abandon the ship.

As soon as the sea permitted, they would launch their two boats, a skiff and a larger lifeboat. Querini decided to draw lots to determine who would take the skiff, a smaller vessel more likely to be lost. He would go in the lifeboat, obviously. On December 27, the sea was just calm enough to launch.

Roughly contemporary woodblock print of a ship in a storm. Photo: Hans Lutzelburger

The lifeboat

The men, the primary accounts record, wept openly and kissed each other on the mouth as they prepared to depart. I wouldn’t normally mention that, but both witness accounts were very clear about it, so it seems to have been a memorable element of the proceedings. At this juncture, while they make final preparations to abandon ship, let me take a moment to introduce our other narrators.

The first primary account of the voyage comes from Querini himself. The second was recorded by a scribe present on the journey from an oral interview with sailors Cristofalo Fioravante and Nicolo de Michiele. We don’t know much about them, except that they were experienced sailors and probably Venetian, based on their dialect. Also, they had ended up assigned to the lifeboat.

It turns out that was their first stroke of good luck in months. The skiff and the 21 men aboard were lost in the night, and nothing more was ever seen of them. The lifeboat, with 47, continued. Laboring under the mistaken belief that they were only about 800 kilometers from Ireland, they tried to make for it before their provisions ran out.

Continuously bailing in an open boat, men immediately began to die. Querini notes that those who led a “dissolute life” went first. After about a week, they cut their watered wine ration to a cup a day. After another week, they were down to half a cup. Some drank seawater and died, while the rest drank their own urine. This is not a good idea, by the way; urine is very salty and will probably just worsen dehydration. They didn’t know that, though.

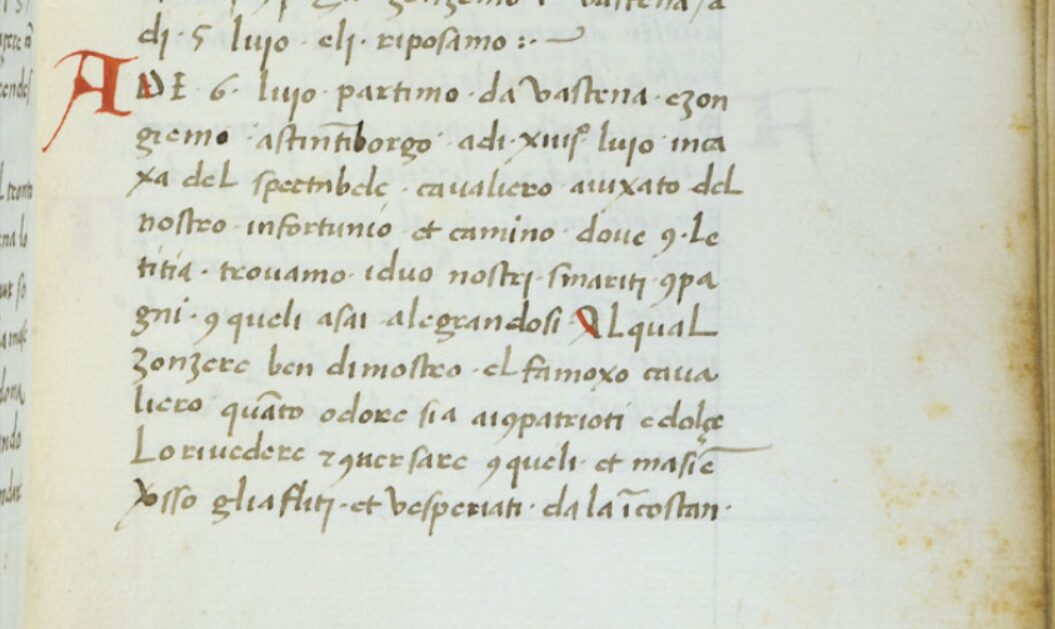

A section of Fioravante and Michiele’s account. Photo: Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, It. VII 368

A dubious salvation

Conditions in the open boat were almost indescribably terrible. Food supplies hadn’t run too low, but the salty, preserved foods worsened their thirst. The boat leaked, requiring constant bailing, and between the cold, the thirst, the bailing, and the tossing waves, sleep was practically impossible.

Their damp clothes and constant exposure to the wind and air worsened the bitter cold. Darkness was nearly constant, with only a few hours of light per day. Fioravante and Michiele say that some of the dying experienced a “rabid and biting frenzy” in their last moments, trying to devour those nearby.

On December 28, Querini confessed that he had had enough and wanted to die as well. He shared out the last of the wine and hunkered down with his head covered. By early January, 26 of the original 47 had died. On January 3, however, a beacon of hope emerged.

Far to windward, off their bow, were snowy rocks. It was impossible to reach them against the wind, but they hoped that by pushing in that general direction, they would come across land again. On January 5, they saw another distant shadow of land. Overjoyed, they took up their oars and tried to row. But they were too weak to row for more than a few hours, and soon they lost sight of the shadow.

The next day, however, they saw another distant island, this time downwind. Breaking waves told them that they had entered an area of rocky shallows, which could wreck their boat. Querini ascribes their successful passage through these shoals to a miraculous wave, while his sailors remember a perceptive bowman. Either way, they escaped destruction and landed among a maze of rocks, on a lone, snowy beach.

One of the Lofoten islands. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Welcome to Sandøya

Though they didn’t know it yet, the exhausted survivors had landed on the small, uninhabited island of Sandøya, in Norway’s Lofoten archipelago, a few hundred kilometers above the Arctic Circle. On the snowy beach, the survivors quenched their thirst with buckets of snow. Nevertheless, several of them immediately died.

Using dried grass and pieces of their oars, they lit a fire and ate some of their scant remaining provisions. In the 19 days since the crew of the Querina had abandoned their ship, the 68 survivors had dwindled to 16. It soon became clear that their small island was uninhabited. But off in the distance, they glimpsed the larger island of Røstlandet, which had signs of life.

Five crewmen got back into the boat to fetch help from the larger island, but almost immediately it began to break apart. It seemed that they had reached land just in time, because their battered boat could carry them no further. Instead, they dismantled it and used it to build two huts. Scraps of wood also went toward feeding their fires.

Condemned, for the moment, to remain on their island, they settled into a painful, bitter existence.

Life in the huts

Thirteen went into the larger hut, and five to the smaller. By that point, their provisions were gone, so they ate sea snails and limpets collected from the seashore, as well as a very sad little soup of snowmelt and grass. Desperate for warmth, they used sail scraps to insulate the huts, which also trapped in smoke. The acrid smoke nearly blinded them as they lay huddled for warmth.

Despite their Arctic environment, vermin were a constant torment. The men’s clothes, hair, and skin were so covered that they threw parasites into the fire by the handful. Worms gnawed the flesh of Querini’s young scribe, “penetrating even to the nerves.” From our modern medical understanding, it seems like frostbite or injury led to necrosis, and maggots bred in the poor scribe’s rotting flesh. Querini and his companions, however, believed that the worms themselves had killed him.

Fioravante and Michiele, with working-class sailor frankness, paint an even more disgusting picture of their conditions. Suffice it to say that their diet of limpets, snow, and grass was not beneficial to the digestion, and conditions did not allow them to leave the hut with the frequency required by dignity or hygiene. Three more men died, and their bodies remained frozen in place among the living.

Querini’s personal servant, Nicolo, was one of the strongest remaining. It was he who, venturing out to gather limpets, found a heartening sight: a small wooden hut.

Norway is home to several species of limpet. They’re a good source of protein, but they probably should not be the only thing you eat. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

An unlikely rescue

There was no one in the building, but from the animal dung nearby and its comparative freshness, he deduced that the island was occupied seasonally. If they could endure until summer, they might be saved. Ten survivors, including our three writers, managed to make the less than a kilometer journey, though Querini found himself so weak that it was difficult. The rest were too sick and lay dying in the shelters.

By a stroke of incredible fortune, a massive, dying fish washed up on the beach. Those who had stayed behind in the boat shelters found new motivation when they smelled cooking food and made it to the hut. Reunited, the party made the fish last ten days, staving off death.

Now, leaving Querini and his men, our story takes us to Røstlandet, the nearby large island. One of the residents there was a fisherman who also kept cattle. During the summer, he would take the cattle to graze on islands like Sandøya. The previous autumn, he’d been unable to find two calves and assumed they had died on the island. But one of his sons, according to their accounts, had a dream that the two calves were alive on the island.

The boy was convinced that his dream was prophetic and bugged his dad until he agreed to go over and take a look. The fisherman and his two teenage sons took their fishing boat to Sandøya, where they were shocked to see smoke rising from their summer hut.

The Lofoten Islands economy was driven by the export of stockfish, preserved cod which fueled long voyages from the Viking age to the 20th century. Photo: Solveig Helland

Venetians in Røst

The Venetians, meanwhile, heard human voices, which they initially mistook for ravens croaking. A crewman named Cristofalo Fioravante, one of the later interviewees, emerged to take a look. Seeing two young men, he called for the rest of the survivors to come out.

The two teenagers, confronted with a dozen filthy, smoke-blind, worm-riddled Italians, were understandably terrified. Querini and his people engaged in a strange sort of charades, attempting to communicate both their distress and their peaceful intentions. Partly assuaged, the teens led them to their father, who quickly realized he was dealing with a classic shipwrecked castaways situation.

Two of their members, Girardo de Lion, a steward, and Colla d’Otrrento, went back with the trio, as no more could fit in the boat. They created quite a stir in Røstlandet, where a Dominican priest was able to speak German with one of the pair. On February 3, the town’s ad hoc rescue party, six fishing boats loaded with food, returned to pick up the rest of the survivors. The townspeople buried the dead and brought the 11 survivors back to the village.

Querini, for all his wealthy patrician background, threw himself at the feet of the fisherman’s wife and kissed them in a show of supplication. The villagers responded in kind, sheltering and feeding their surprise visitors until spring came. Both accounts spend several pages describing the sleepy, 120-person fishing village and extolling the villagers’ unselfish kindness toward them.

Monument to Querini and his men, Sandøya. Photo: Via Querinissima

The long return

On May 14, it was finally time to leave. Their host, the fisherman, was taking a ship loaded with fish to Bergen, on the mainland. The villagers loaded the Venetians with fish for their journey, and they finally set off toward home. This was still the 15th century, though, so it was going to take a while.

War had broken out between Norway and Germany, so instead of Bergen, they were dropped off early in Trondheim. Querini, able to converse with high church officials in the shared language of Latin, won the assistance of an archbishop, who supplied them and hired guides for their long overland journey out of Norway. Crossing into Sweden, they made time for a bit of tourism, visiting several holy sites. Eventually, they came to an area which is now Gothenburg, and here the party split.

Fioravanti and Michiel, along with Corrado di Lione, went overland to Venice, via Germany. Querini made for London with the rest of the crew, where they again met with generous hosts. In fact, it was two months before the survivors were allowed to stop feasting and go home.

The boatswain discovered that his wife, believing him dead, had remarried. When she learned the truth, she did leave her new husband and return to him, so all’s well that ends well on that front.

The people of Røst never forgot Querini and his men. In 1932, they erected a monument on Sandøya. In 2012, they put on an opera about the voyage of the Querina. There is also a Querini-themed pub and restaurant there, though I was unable to ascertain whether or not they serve limpet.