Of the 514 people who summited Annapurna I by the end of 2024, only six did so in winter. Twenty-three expeditions have tried to ascend Annapurna I in the coldest season, including 19 without bottled oxygen. Only two of those teams were successful.

Between 1950 and 1964, all 14 of the 8,000’ers were climbed for the first time, but none in winter. The first 8,000m peak summited in winter was Everest. On Feb. 17, 1980, Leszek Cichy and Krzysztof Wielicki of Poland reached the top with supplemental oxygen.

Annapurna I became the sixth 8,000 peak climbed in winter, after Everest, Manaslu, Dhaulagiri I, Cho Oyu, and Kangchenjunga. On Feb. 3, 1987, Artur Hajzer and Jerzy Kukuczka, also from Poland, summited 8,091m Annapurna I at this time of year for the first time. Thanks to detailed expedition reports, we can get a taste of just how hard it is to climb an 8,000m peak in winter.

Annapurna I in winter 2024 shows a foreground crevasse, and behind, the Great Couloir. Photo: Moeses Fiamoncini

Early winter attempts

Before its first successful ascent, seven expeditions had tried and failed to climb Annapurna I in winter.

On Jan. 27, 1981, Naoe Sakashita from Japan attempted the North Face without using bottled oxygen. Ang Phurba Sherpa and Pasang Norbu Sherpa accompanied him. According to The Himalayan Database, their highest point was 6,700m. Because of bad weather, it was not possible to go higher.

Two years later, Tadao Sugimoto led a group from the Tokyo Shigaku Club Expedition to Annapurna I. They arrived at Base Camp in late November, 1983. The team included Yu Watanabe, Kenji Imada, Kunihiro Kajimura, and three sherpas. They also attempted the North Face route without O2. (Note that before the modern commercial era, most climbers attempted Annapurna I without oxygen.)

Sugimoto’s party eventually abandoned their attempt on December 18. Things had not gone well. Winds were relentlessly strong. A piece of ice struck Panima Sherpa between Camp 2 (5,400m) and Camp 3 (6,200m). Watanabe and Imada frostbit their toes so badly on the day the expedition ended that eventually, they needed partial amputations. Also on December 18, Phurba Tshering Sherpa fell into a crevasse near Camp 3 and hurt his back.

Annapurna I’s normal route. Photo: Ferran Latorre

Winter 1984-85

In 1984-85, three winter expeditions attempted Annapurna I.

On November 18, 1984, a third Japanese party showed up. The Japan Gunma Winter Annapurna I Expedition, led by Kuniaki Yagihara, was a big team that included 15 Japanese and eight climbing sherpas. They attempted the Bonington route on the South Face with bottled oxygen. However, bad weather, including lots of snow, plagued them for weeks.

On their first attempt, on December 29, the Japanese reached 7,200m. There, the deep snow forced them to turn back to Base Camp. After waiting for nine days, they tried again. They wanted to reach Camp 4 at 6,950m but were afraid of avalanches, so retreated to Camp 3 at 6,500m. Several sherpas decided not to continue climbing. More snow fell, and the expedition ended.

The South Face of Annapurna I. Photo: Shutterstock

That same winter, a French expedition led by Bernard Muller attempted the 1950 French route without bottled oxygen. Muller’s party arrived at Base Camp on November 27 and included six French climbers and one climbing sherpa.

On December 2, they had to abandon their attempt at 6,000m due to serac avalanches and strong winds that even blew down a tent in Base Camp.

Controversy: a false claim

The third 1984-85 expedition was from South Korea, led by Ahn Chang-Yeul, and included five Korean nationals and three climbing sherpas. They targeted the North Face by the Dutch Rib with supplemental oxygen. The South Koreans claimed that one of the climbers, a woman named Young-Ja Kim, summited with four sherpas on December 7, but this claim was disputed and eventually proven false.

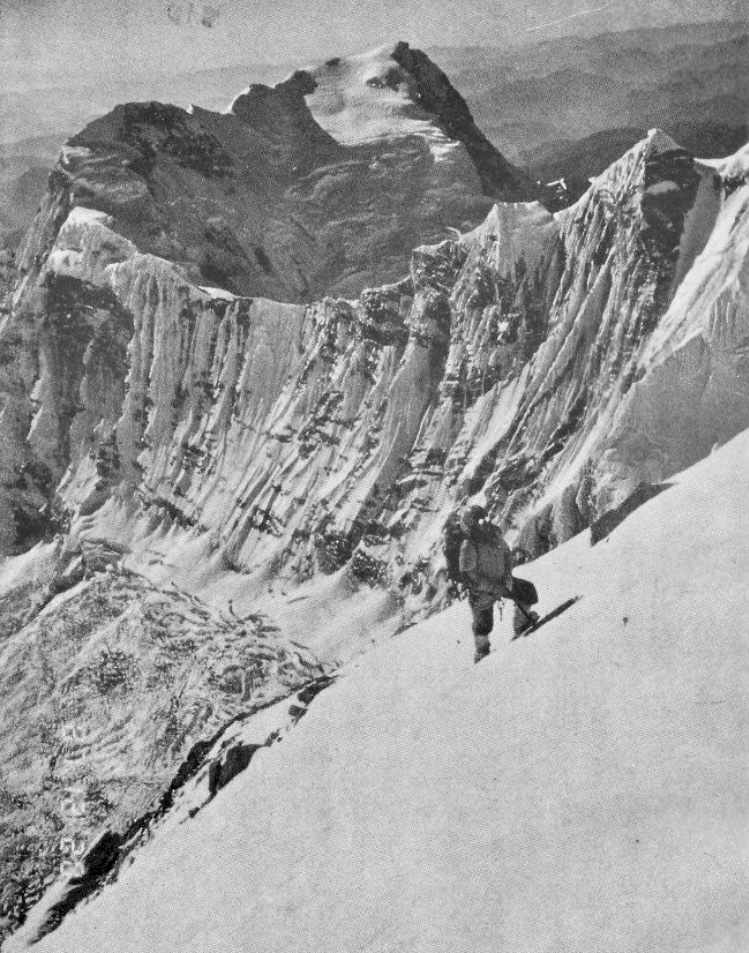

From the Polish winter Annapurna I expedition. Photo: Jerzy Kukuczka archive

Bernard Muller, the French leader who was also on the north side of Annapurna I, said that he and his men saw the South Korean team through binoculars. They were below and well to the east of the main summit — too far away to have reached the top in the time claimed.

According to the Koreans’ entry in The Himalayan Database, they had taken eight hours from their Camp 4 to the summit. Based on their sighting, the French estimated that it would have taken the Koreans an additional two hours to summit in that day’s very strong winds. Additionally, the sherpas working for the Koreans told the French sherpas that no one reached the top.

It eventually became clear that Young-Ja Kim and her group had actually reached the middle summit of Annapurna I rather than the main one.

On the South Face of Annapurna I, autumn 2013. Photo: Ueli Steck

Bulgarian and Swiss South Face attempts

A year later, on Nov. 10, 1985, a large Bulgarian team of 16 climbers and four sherpas arrived at Base Camp. Their leader was Boyan Atanassov, and they targeted the South Face (Polish route) without bottled oxygen. The Bulgarians reached 7,300m on January 25, 1986, before turning back because of bad weather.

In the winter of 1986, Daniel Anker and Rene Brinkmann of Switzerland came to Base Camp on November 12 to try the South Face (Spanish route) without supplemental oxygen. The two Swiss had no sherpas above Base Camp. They persisted until the end of November but only reached 5,300m before turning around due to Brinkmann’s poor health.

The Polish team. Photo: Jerzy Kukuczka Archive

Kukuczka and the Poles

The legendary Jerzy Kukuczka organized an expedition to Annapurna I in the winter of 1986-87.

The team included Artur Hajzer, Jacek Palkiewicz, Wanda Rutkiewicz, Michel Tokorzewski, Ryszard Warecki, and Krzysztof Wielicki. They opted for the original 1950 French route on the North Face, without bottled oxygen or sherpas.

Earlier that year, Kukuczka had climbed three other 8,000’ers: Kangchenjunga, K2, and Manaslu.

The expedition arrived at Base Camp (4,200m) quite late, on January 18, 1987, leaving little time for a winter ascent. But Kukuczka and Hajzer were already well-acclimatized from summiting Manaslu on November 10 without bottled oxygen.

Wanda Rutkiewicz crosses a crevasse on Annapurna during the winter expedition. Photo: Jerzy Kukuczka Archive

On January 20, the small team started up and established Camp 3 two days later at 6,100m, where they spent the night. The next day, they climbed a further 100m. Rutkiewicz had health problems, and fresh snow made progress difficult, so on January 23, they descended to Base Camp.

In the following days, the climbers moved in small groups between the lower camps. On January 29, four of them reached Camp 3. The next day, they traversed into the couloir on dangerous hard ice, as avalanches unleashed snow, stones, and ice upon them. They bivouacked at 6,500m near the couloir.

That night, falling rocks destroyed their tent, but the next day, they continued to Camp 4 at 6,800m.

Krzysztof Wielicki, left, and Artur Hajzer. Photo: Jerzy Kukuczka Archive

Winter summit at last

On February 1, Kukuczka and Hajzer headed up toward Camp 5 at 7,400m in poor visibility, climbing on ice as hard as glass. On February 2, 40cm of snow fell, and the two climbers stayed at Camp 2.

The next day, they started their final push for the summit, fighting through 50cm of fresh snow below the top. Hajzer and Kukuczka finally topped out on February 3 at 4 pm.

Artur Hajzer on the summit of Annapurna I. Photo: Jerzy Kukuczka

They struggled during the descent because of poor visibility and only reached their high camp at 7,400m at 10 pm. Visibility problems continued the next day, but they eventually reached Base Camp on February 5.

Jerzy Kukuczka on the summit of Annapurna I. Photo: Artur Hajzer

The South Face in winter

Annapurna I had one more successful winter ascent. That was in December 1987, by a Japanese expedition.

The Gunma Mountaineering Federation, led by Kuniaki Yagihara, returned to the mountain on Nov. 23, 1987. The team included 14 Japanese (including six-time 8,000m summiter Noboru Yamada) and 14 sherpas. No one used bottled oxygen.

The Japanese party chose the risky and difficult Bonington South Face route of 1970, with a slight variation on the lower part. According to Yagihara’s report, Bonington’s ridge was very bad because of loose snow, so the Japanese took a couloir to its left. This was not much better due to ice-hard snow, which was difficult to climb.

Between Camp 3 (6,850m) and Camp 4 (7,400m), they rejoined the Bonington route. Loose pieces of unstable rock fell frequently, injuring one Japanese and a sherpa. They even had to change the site of Camp 3 twice, because avalanches and falling rocks destroyed their original campsite.

On December 20, Toshiyuki Kobayashi, Teruo Saegusa, Yasuhira Saito, and Noboru Yamada topped out at 3:15 pm.

On the south face of Annapurna I. Photo: Kuniaki Yagihara

Deadly falls

The successful summit turned tragic during the descent for two of the exhausted climbers. That day, at 5 pm, Kobayashi fell from 7,900m. Two hours later, Saito, too, fell from 7,420m. Both climbers died. (For more about this expedition, follow this link.)

Since then, three more have died in winter on Annapurna I. On December 5, 1994, Suk-Byun Jun of South Korea died in a fall on the mountain’s lower section. On December 25, 1997, two great Kazakh mountaineers, Anatoli Boukreev and Dmitri Sobolev, perished in an avalanche.

Anatoli Boukreev. Photo: Anatoli Boukreev