As in mountaineering, there are still more men than women climbing on ice. However, this is changing. Women like Ines Papert, Dawn Glanc, Angelika Rainer, Nathalie Fortin, Anna Pfaff, Elaina Arenz, Cecilia Buil, Sarah Hueniken, Ixchel Foord, Anna Torretta, and Majka Burhardt are bringing attention to women’s ice climbing.

It is a long, inspiring list. Many of these women have been pushing their limits on ice for more than 20 years.

Dawn Glanc climbing in Ouray Ice Park. The park is open to the public from December to March and has over 150 routes. Photo: Michael Clark

Where do they climb?

For those looking to climb ice waterfalls, some places have become almost mythical. These include the Canmore-Banff area of the Canadian Rockies, Ouray Ice Park in Colorado, Rjukan in Norway, Kandersteg in Switzerland, Helmcken Falls in British Columbia, and Cogne in the Aosta Valley in Italy.

Those who live near these areas are currently preparing for winter’s arrival. New climbers can sign up for ice climbing classes to learn from veteran guides.

Dawn Glanc climbs in Ouray Park, Colorado. The park is open to anyone and ice climbing courses are available. Photo: Michael Clark

Exploration, the ultimate joy

Away from the well-known spots, professional climbers continue to explore new possibilities.

“The idea of research, preparation, and approach is super cool!” Dawn Glanc says. Glanc, a climbing instructor with the American Mountain Guide Association, is an incredible source of ice climbing knowledge and wisdom.

Dawn Glanc and friends in Iceland, where they opened several new routes on ice. Photo: Keith Ladzinski

Between 2012 and 2017, she traveled to the west fiords of Iceland. She and her team notched many first ascents near Isafjordur and Bildudalur.

“I took the map and put circles on each point of the fiords where I thought there was surely a frozen waterfall,” she said. “Going to a place that no guidebook has written about, where there are only topos with circles, and getting there to find that ice, is very rewarding. And when you open a route, it is not a feeling of accomplishment or success, but rather one of deep respect.”

Spanish climber Cecilia Buil has climbed big walls all over the world, from the Karakorum, the Himalaya, and Yosemite to El Gigante in Mexico.

“I felt that I needed to expand my knowledge and not feel limited,” says Buil. “In the Karakorum, I liked to climb big walls. I realized that at the top, there was always ice. For me, it was not love at first sight. At first, I was very scared and very cold. But over time, I realized that I was enjoying to the fullest something that used to terrify me.”

Spain’s Cecilia Buil travels to remote places to find frozen waterfalls. Photo: Cecilia Buil

Buil has now been climbing ice waterfalls for more than 20 years. Away from the crowded mountains, she is a free soul. Some time ago, she set a personal goal to make the first ascent of a frozen waterfall on every continent. In 2014, Buil, Anna Torretta, and Ixchel Foord, went to Cerro Marmolejo in Chile. There, they made the first ascent of Gioconda, a 160m climb above 4,000m.

Ever-changing ice

Ixchel Foord, a strong Mexican climber on both big walls and ice, describes her love of ice climbing:

“It all started as a dream,” Foord told Explorersweb. “An idea was born. When working on that idea, the objective, then the action, the affection, and in the end, the commitment arose. That is why opening new routes with Cecilia [Buil] means total adventure for me. The changeable color of the ice, and understanding it, make me enjoy it even more.

Ixchel Foord climbing the ‘Lynx’ in Canada. Photo: Ixchel Foord

Ice climbers often have to wait for their route to form. Sometimes an ice waterfall won’t form at all, or it takes on an unexpected shape. Climbers may travel thousands of kilometres and won’t know if the ice waterfalls are ready until they arrive. However, some are lucky enough to live close to their climbs.

Sarah Hueniken lives in Canmore and has been guiding in the Canadian Rockies for more than 20 years. “When winter comes to Canmore, you know that ice waterfalls start to form out there in the mountains. It’s exciting to hunt these waterfalls,” Hueniken explains.

Sarah Hueniken became the second person, and the first woman, to climb the rarely frozen Niagara Falls. Photo: Sarah Hueniken

The secret life of the ice

Each route is unique. There are ice waterfalls attached to the rock when the water flows down them and freezes. Others are free-standing or free-hanging. Some waterfalls only make up part of the route, creating mixed lines.

Icicles can form in incredible shapes. The textures, colors, columns, and shapes depend on several factors. The wind, sun, geography, volume of water, and temperature changes all combine to create something special.

Climber Jeff Lowe described at least 13 different types of ice. His list included verglas, the finest type, with a maximum thickness of 1.3 cm; laminated flow, created by successive freezing of thin layers of ice; chandeliered ice, marked by clusters of hanging icicles; and plastic ice, which is warm but not rotten. Plastic ice is best for ice climbing.

One famous frozen waterfall is called Lipton Ice. It is found in Rjukan in Norway and the mineralized ice has a yellow color.

The Lipton Ice route, in Rjukan, Norway. Photo: Cecilia Buil

“It is one of the most beautiful waterfalls I have seen, and the truth is that it makes me a bit tense,” Buil said in 2012 when she first decided to climb the WI7 route.

Buil explains that ice can be very scary and dangerous because it is so changeable. “There is a very strong psychological component,” she said. “I like being close to my limit and pushing myself to another level. Fear is necessary…and it helps me to be alive. Ice is something very ephemeral, it forms, it grows, and there comes a moment when the conditions are perfect. You have to be prepared to climb at that moment.”

Knowing the ice

“Knowing where you are going to move is essential,” Foord explains. “On ice, you cannot afford to fall because anchors can be precarious or scarce. A fall can do a lot of damage. As well as the blow you may suffer, you carry sharp tools.”

Ixchel Foord and Cecilia Buil read the route before they climb. Photo: Ixchel Foord

In 2006, the Petzl Foundation launched a research program to study waterfall ice, in partnership with Grenoble’s Laboratory of Glaciology and Environmental Geophysics.

The research program found that for waterfall ice to form, there is ideally a period of stable temperature close to 0°C. During this time, there needs to be minimal melting during the day and no sudden cooling at night. If there is a period of warmer weather above 0°C, the passage of liquid water over the ice/rock can cause the ice to disengage from the base.

Sudden cooling followed by a period of intense cold causes strong thermal contractions in the ice. The ice shrinks from the cold and becomes brittle. If hit with an ice ax, fissures in the ice may widen and the ice could collapse.

An ice pillar in Colorado, known as ‘The Fang’. Climber Sam Elias heads up. Photo: Reddit

Managing fear

Ice climbers emphasize the importance of respect.

“The route may change during the climb, and this must be taken into account,” Glanc told Explorersweb.

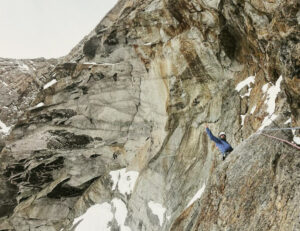

Dawn Glanc climbs ‘Red Bull Vodka’ in the Vail, Colorado amphitheater. In 2014, she became the first woman in the United States to climb M11. Photo: Fred Marmsater

Sometimes even the approach is difficult. This was the case for Foord and Buil in Canada when they took on a new line on the classic Weeping Wall in the Rockies.

“Ice climbing can be fun and scary, with no middle ground in between,” Glanc says. “To deal with the fear, I use self-coaching skills and go back to basic movement techniques. Because ice climbing is so systematic, I can rely on that basic structure to help me relax and deal with fear.”

What skills do you need?

Technique is key. It must be developed step by step.

“For ice climbing, balance is more important than strength,” Glanc says. “Women may be better suited [to ice climbing] for this reason. If you have taken yoga classes and know how to dance, you have an important advantage and you can quickly progress.”

When planning exploratory adventures, women also tend to tie the details together well.

“Before I take off up a climb, I have weighed many factors to determine the safety of the climb,” says Glanc. “I consider the weather, temperature, sun exposure, and visible water. Once I am on the climb, I am constantly evaluating the consistency, color, sound, and texture of the ice.”